Adolf Hitler greeting Colonel-General Ferdinand Schoerner inside the Führerbunker, April 1945.

There are few stories as enigmatic as the last days in the Berlin Bunker. Historians cannot agree on what exactly occurred 8.5 metres below the Reichs Chancellery garden, providing for some intriguing theories. As I was in Berlin exactly 71 years to the month of Hitler’s death, I thought I’d see what remains. The answer is ‘not a lot’, but with a little detective work, some maps, some old photos and a splash of imagination its possible to find yourself standing on the spot where the final death throes of the Thousand Year Reich were played out.

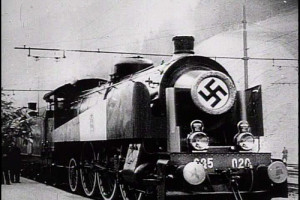

Following the failure of the last German offensive in the West, a dispirited Hitler returned to Berlin on 16 January 1945 aboard his private train, the Führersonderzug.

As the long train wound its way through the devastated capital Hitler reportedly looked out at the ruins from his Pullman carriage, both surprised and depressed by the grim sights that greeted him. He needed no more than to look out the window to see the reality of his military failure.

The bomb destroyed spire of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church today.

Arriving at Grunewald Station at 9.40am, Hitler climbed down from the Führersonderzug for the last time and was driven in a convoy of armoured Mercedes to the Reichs Chancellery, passing through bomb-damaged streets whose gutted and roofless apartment buildings and shops bore silent witness to the final collapse of the Third Reich.

A huge Soviet winter offensive began just two days later. By the end of the month the Soviets were only seventy miles from Berlin. Hitler continued to live in his apartments in the Old Reichs Chancellery until mid-February before moving into the Führerbunker to sleep. Until mid-March 1945 Hitler also continued to take his meals in the New Reichs Chancellery and to hold his military situation conferences there inside his enormous study. The grand hallway outside was still intact, though the artworks and priceless tapestries had been removed to protect them from the bombing.

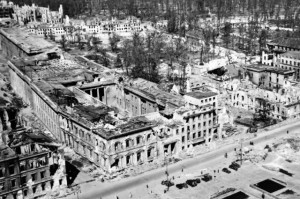

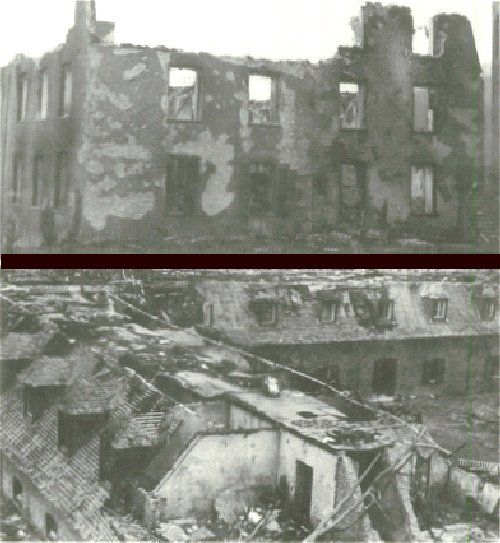

The bomb-ravaged Reichs Chancellery in May 1945

Although Hitler continued to come up from the Führerbunker into both Chancelleries, to continue working in his study and used some of the building’s other rooms, he did not see the vast amount of damage that had been caused to both buildings by British and American aerial bombing. Staff officers visiting the Reichs Chancellery for meetings had to take long and circuitous routes to reach Hitler’s study, as corridors had been reduced to rubble by direct hits. Soon the Reichs Chancellery would start to come under artillery and rocket fire from the advancing Red Army.

A view of the Führerbunker’s emergency exit (the concrete cube on the left) in the ruined Old Reichs Chancellery Garden in 1947.

The same view in April 2016. The emergency exit and conical guard tower would stand about halfway into the current road. The remains of the Führerbunker still exist below the road and pedestrian path. The Vorbunker or Upper Bunker has been removed.

The same view in April 2016. The emergency exit and conical guard tower would stand about halfway into the current road. The remains of the Führerbunker still exist below the road and pedestrian path. The Vorbunker or Upper Bunker has been removed.

Because of the constant bombing raids and air raid alerts Hitler decided to move his headquarters underground into the Führerbunker beneath the Old Reichs Chancellery gardens in mid-March 1945. Although now safe from aerial attack, the Führerbunker was completely inadequate for use as a military headquarters as it was too small to accommodate sufficient staff or visiting generals attending conferences. It came to be described by many who visited it during the last weeks of the war as a fetid hole in the ground or a ‘concrete coffin’.

One of Hitler’s last public appearances – congratulating Hitler Youths who had been awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class fighting the Soviets in East Prussia. A stooped and exhausted Hitler is pictured walking to the ceremony in the Reichs Chancellery Garden on 21 March 1945. Other leading ‘Bunker’ personalities in the photo are, third from left Hitler Youth Leader Artur Axmann, 4th from left SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein, Himmler’s liaison at the Bunker, 5th from left SS-Obergruppenführer Julius Schaub, Hitler’s adjutant.

One of Hitler’s last public appearances – congratulating Hitler Youths who had been awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class fighting the Soviets in East Prussia. A stooped and exhausted Hitler is pictured walking to the ceremony in the Reichs Chancellery Garden on 21 March 1945. Other leading ‘Bunker’ personalities in the photo are, third from left Hitler Youth Leader Artur Axmann, 4th from left SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein, Himmler’s liaison at the Bunker, 5th from left SS-Obergruppenführer Julius Schaub, Hitler’s adjutant.

The Führerbunker had its genesis in air raid shelters built under and adjoined to buildings on Wilhelmstrasse and Vossstrasse in 1935. When the New Reichs Chancellery complex was completed in January 1939 it included more air raid shelters. One was the Vorbunker, or Upper Bunker. Architect Leonhard Gall submitted plans in 1935 for a large reception hall cum ballroom to be added to the Old Reichs Chancellery. Completed in 1936, the Vorbunker had a roof that was 5.24 feet (1.6 m) thick, the bunker’s thick walls partially supporting the weight of the large reception hall overhead.

A Nazi eagle salvaged from the Reichs Chancellery in 1945, and now displayed at the Imperial War Museum, London.

Some idea of the scale and style of the New Reichs Chancellery can be derived from one of two surviving Nazi-era ministry building in Berlin – Hermann Goring’s Air Ministry on Wilhelmstrasse. The other is Dr. Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry.

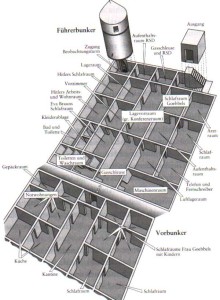

There were two entrances into the Vorbunker; one from the Foreign Ministry garden and the other from the New Reichs Chancellery. Both led to a reinforced steel gas proof door leading to a set of small rooms.

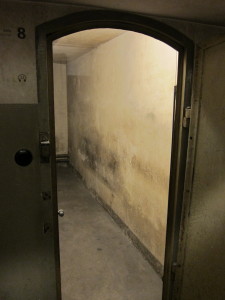

This photo is of the interior of the SS bunker beneath Hitler’s house, the Berghof, on the Obersalzberg in Bavaria. It hints at the look of the Berlin bunker.

On the left was the Water Supplies/Boiler Room, to the right the Airfilters Room. Moving forward there was a middle Dining Area with a Kitchen to the left, which was where Hitler’s cook/dietician Frau Constanze Manziarly prepared the Führer’s meals. There was also a well-stocked Wine Store. To the right of the Dining Area was the Personnel/Guard Quarters. Moving forward again, there was a Conference Room in the middle and on the left two rooms that originally housed Hitler’s physician Dr. Theodor Morell and, following his dismissal in April 1945, Dr. Goebbels’ wife Magda and her six young children. To the right of the Conference Room was a room used for guest quarters, two storerooms and then a stairway set at right angles connecting to the Führerbunker that was 8.2 feet (2.5 m) lower than the Vorbunker and west-southwest of it. Steel doors could close off the Vorbunker and Führerbunker from one another and the SS closely guarded all entrances and exits.

Beneath this nondescript patch of grass was the connecting staircase between the Vorbunker (Upper Bunker) on the right, which was constructed beneath the Reichschancellery and the deeper Führerbunker (left)

Hitler’s Führerbunker, or Lower Bunker, was built in 1942-43 28 feet (8.5 m) beneath the Old Reichs Chancellery Garden 131 yards (120 m) north of the New Chancellery at a cost of 1.4 million Reichsmarks. It was deep enough to withstand the largest bombs that were being dropped by the British and Americans over the city.

Designed by the architectural firm Hochtief under Albert Speer’s supervision, the Führerbunker was one of about twenty bunkers and air raid shelters used by Hitler’s inner circle, bodyguards and military commanders in the region of the Reichs Chancellery. Many cellars in the surrounding buildings were also utilised as auxiliary bunkers during the Battle of Berlin.

The Führerbunker suffered from noise caused by the steady running of aeration ventilators twenty-four hours a day and also had a problem with cool moisture on the walls as Berlin has a very high ground water level.

Steel safes photographed inside the Vorbunker by an East German in 1987, when the authorities pumped out the upper bunker preparatory to destroying it.

Entry into the Führerbunker was via the Vorbunker, passing down the dogleg staircase, which led to a guarded door giving access to a long Hall/Lounge, where RSD and SS-Begleit-Kommando sentries checked identity papers before permitting entry to the Führerbunker proper.

This was through double steel gas proof doors set into the bunker’s 7.2 feet (2.2m) thick protective wall. The Führerbunker was divided along a central corridor that gave access to an emergency exit staircase at the far end that led up to the surface in the Reichs Chancellery Garden.

Another 1987 shot of the Vorbunker. This structure has now been erased, though the Fuhrerbunker remains intact 2.5m beneath.

This corridor was divided into two long rooms. The first of these on entering the Führerbunker was the Corridor/Lounge. A door on the left led to the Toilets and Electricity Switch Room. From the Toilets a connecting door led to the Bathroom/Dressing Room with Eva Braun’s Bedroom on the right of the Bathroom.

View behind the Vorbunker looking towards the Führerbunker today. In 1945 you would have been standing inside the Old Reichs Chancellery.

A door connected the Bathroom with Hitler’s Sitting Room. To the right of this room was Hitler’s Study, dominated by a large painting of King Frederick the Great that Hitler would spend much time staring at as the Soviets fought their way into Berlin’s suburbs, hoping that he could emulate Frederick and turn back the Bolshevik horde with some final grand military gesture.

A recreation of Hitler’s study in a German museum – this was where Hitler and his wife killed themselves.

A door connected Hitler’s Sitting Room with Hitler’s Bedroom. A door on the right of Hitler’s Study led back into the central corridor, this section called the Conference Room.

Mark standing above Hitler’s suite of rooms that still exist 8.5 metres below ground.

The last three rooms on the left of the Führerbunker were not connected to Hitler’s suite and consisted of the Map Room where Hitler held most of his military situation conferences during the last weeks of the war, the Cloakroom and a Ventilation Room.

The left side of the Führerbunker consisted, moving from the staircase connecting it with the Vorbunker to the emergency exit tothe Reichs Chancellery Gardens, of a series of rooms. First was the Generator/Ventilation Plant Room. This was connected to the Telephone Switchboard Room where SS-Oberscharführer Rochus Misch of the SS-Begleit-Kommando worked, Martin Bormann’s Office and the Guard Room. Hitler’s loyal valet SS-Obersturmbannführer Heinz Linge lived here. Next were two rooms: Goebbels’ Office and the Doctor’s Room. The last two rooms on the right of the central Conference Room were Goebbels’ Bedroom and the Doctor’s Quarters. Parts of the two bunkers were carpeted and one section of this material was recently discovered in a British regimental archive. It reveals that the carpet had a floral pattern of yellow flowers and blue leaves on a fawn background. The rooms were furnished with expensive pieces taken from the Reichs Chancellery above and there were several framed oil paintings on the walls. But the interior, in keeping with Hitler’s other field headquarters, could not be described as anything other than Spartan and functional.

Hitler viewing bomb damage inside the Reichs Chancellery, April 1945 (purportedly the last picture ever taken of Hitler)

On 16 April the Red Army commenced the operation to capture Berlin, assaulting the Seelow Heights, the last significant German defence line east of the city. The fighting was fierce, the Soviets suffering heavy casualties, but by the 19th they had broken though and there was now no longer a proper defence position left to protect the city.

On 20 April, Hitler’s 56th birthday, Soviet artillery came in range of the Berlin suburbs and opened fire. By the next evening T-34 tanks had arrived on the outskirts.

Soviet T-34 that fought in the battle mounted on a plinth along the East-West Axis through the Tiergarten, Berlin.

As the Red Army began to close a ring around Berlin and began to fight through the city suburbs in several directions aiming for the nearby Reichstag building, efforts were taken to increase the protection afforded to the Reichs Chancellery and the Führerbunker.

Severe battle damage on the Brandenburg Gate three minutes walk from Hitler’s bunker. When Hitler died, the Soviets were at the nearby Reichstag and very close to the Gate.

On 22 April 1945 Kampfgruppe Mohnke was formed out of all available elite guard units from across Berlin and sent to defend the government quarter, Sector Z (Citadel), from the Soviets. Its commander, 34-year-old SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke had been one of the founding members of the SS-Stabswache (Staff Guard) in Berlin in 1934. A highly decorated Waffen–SS field commander, by 1945 Mohnke commanded the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler Division.

A Soviet heavy artillery gun from the battle preserved on Berlin’s East-West Axis near the Brandenburg Gate.

By 22 April the Germans defending Berlin were outnumbered virtually 10-1, German units had been severely degraded and worn down by almost continuous fighting since the start of the Soviet spring offensive in January. One hundred thousand Volkssturm, mostly consisting of older men above military age, Hitler Youth and foreign SS volunteers, was backing up the regular troops in the hopeless defence.

With virtually no tanks, limited artillery and no viable Luftwaffe over the capital, the defence of Berlin would not last for long.

The focus of the Soviet assaults was the Reichstag, abandoned since 1933, close to the Chancellery and Hitler’s bunker

The repaired (though heavily scarred) Reichstag from the same angle today.

Hitler grasped at anything that he thought might turn the tide. When he observed the vulnerability of one of the Soviet flanks he gave orders for SS-Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner’s Army Detachment to counterattack, refusing to accept that Steiner’s forces were severely depleted and simply not up to the task. When Hitler discovered at the afternoon situation conference in the bunker that Steiner had failed to attack he suffered a complete mental collapse and once he stopped screaming declared to his shocked audience that the war was lost. Later that day Hitler consulted SS-Obersturmbannführer Prof. Dr. Werner Haase on the best method to kill oneself. Haase suggested that he bite down on a cyanide capsule whilst simultaneously shooting himself in the head.

By the last week of April 1945 Hitler’s world had shrunk to a few grey concrete rooms deep beneath the Reichs Chancellery Garden in Berlin. Up above, Soviet artillery shells and rockets blasted the once immaculate Chancellery buildings into ruins. Huge sections of roof and walls had collapsed, while the remaining structures were shell- and shrapnel-scarred, fire scorched or windowless.

The Reichs Chancellery Garden, its trees blasted and stripped of their foliage and the lawn churned up by shell craters, was only passable between bombardments and Hitler’s RSD and SS-Begleit-Kommando guards were largely withdrawn from exposed sentry posts on the Chancellery roof and outside the bunker entrances. Each time another Soviet barrage went up the guards fled inside the bunker entrances, slamming the thick steel doors closed behind them. Hitler forbade smoking in the Führerbunker, so smokers had to go up to the Vorbunker to enjoy a cigarette. With their nerves on edge, many of the bunker inhabitants were smoking and drinking heavily. Some hardier souls would emerge into the shattered gardens to smoke or catch a few minutes of fresh air before Soviet shelling forced them once more into the dank subterranean bunkers, while Hitler’s dog Blondi was still walked in the garden by his handler.

Hitler & Blondi on the Obersalzberg

Hitler & Blondi on the Obersalzberg

By 27 April 1945 Berlin was completely surrounded. The bunker had lost secure radio communications with the main German units fighting desperately in the ruins and had to rely on the telephone network for news. To all intents and purposes the last Führer Headquarters was blind and incapable of really commanding anything. Soviet troops were on the Alexanderplatz and would soon reach the Potsdamer Platz, where the bunker was located. Efforts were still being made to affect a linkup between the remnants of the 9th Army defending the city and General Wenck’s 12th Army that was attempting to fight its way into Potsdam.

The famous Victory Column on the East-West Axis in 2016 (above) and 1945 (below)

As this last desperate attempt was being made SS-Brigadeführer Mohnke reported that enemy tanks had penetrated the nearby Wilhelmsplatz – they had been repulsed this time, but time was running out.

The following day’s news of Heinrich Himmler’s entreaties to the Western Allies reached the bunker. Hitler was incensed and ordered Himmler’s arrest for treason. He demanded to see SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein, Himmler’s representative in the bunker, but he was nowhere to be found. An RSD snatch squad was dispatched that discovered Fegelein in his apartment with his mistress, drunk and with a suitcase of civilian clothes packed along with false identity papers. He was escorted back to the bunker, summarily sentenced to death by a court martial and shot in the Reichs Chancellery garden. By now, the Red Army was at the Potsdammer Platz and was evidently preparing to storm the Reichs Chancellery.

The Brandenburg Gate 1945 and 2016

Topside, the remaining men of Kampfgruppe Mohnke fought the Soviets around the Chancellery site from prepared positions and a multitude of other bunkers and cellars, as well as utilizing the remaining portions of the underground railway system that was still in German hands. The French SS of the Charlemagne Division in particular distinguished themselves as tank destroyers, knocking out dozens of Soviet T-34s with handheld Panzerfaust rocket launchers. Ironically, it was two Frenchmen who were the last soldiers to be decorated with Nazi Germany’s highest bravery award, the Knight’s Cross. Ammunition supplies were dwindling rapidly alongside the mounting casualties. The main Reichs Chancellery bunker had been transformed into an emergency casualty clearing station and refuge.

Knowing that the end was near seemed to make up Hitler’s mind concerning a personal matter. Just after midnight on 30 April Hitler married his longtime girlfriend Eva Braun in a simple ceremony inside the bunker. It was her reward for her years of loyalty to him. She was under no illusions – she had come to Berlin to die with Hitler.

At 1am on 30 May Generalfeldmarschall Keitel reported to Hitler that all German forces that had been ordered to relieve the capital were either surrounded or had been forced on to the defensive. No relief of the government quarter could be expected. Later that morning the attacking Soviets managed to penetrate to within 1,600 feet (500m) of the Führerbunker, despite the fanatical resistance being put up by Hitler’s guard detachments. Hitler met with General der Artillerie Helmuth Weidling, the commander of the Berlin Defence Area. He informed the Führer that there was enough ammunition to sustain the defence for a maximum of twenty-four hours. Weidling asked permission for the remaining troops to attempt a breakout, but Hitler did not reply. Weidling returned to his headquarters at the Bendlerblock. At 1pm he received permission from Hitler for a breakout.

Hitler had lunch with two of his secretaries and his cook and then he bade farewell to his staff and the remaining bunker occupants, including Bormann and Goebbels. With his wife, Hitler went into his study and closed the door at 2.30pm. Differing accounts of what happened next have surfaced over the years. The officially accepted story is that at shortly after 3.30pm Heinz Linge, with Bormann right behind him, opened the study door and was met with the strong smell of burnt almonds, a signature of hydrogen cyanide. Again accounts differ in the details but according to Linge, Eva Hitler was slumped to the left of the Führer on a sofa, her legs drawn up. Hitler ‘sat…sunken over, with blood dripping out of his right temple,’ wrote Linge. ‘He had shot himself with his own pistol, a Walther PPK 7.65.’

Hitler shot himself somewhere below this modern pavement. Due to the redevelopment of the area by the East Germans it is almost impossible to visualise how it looked in 1945.

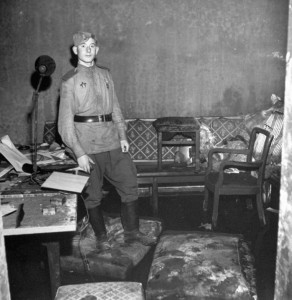

A Red Army soldier inside Hitler’s study deep in the Bunker shortly after its capture. Flooding has occurred after the pumps were switched off, due to Berlin’s high water table.

Hitler’s adjutant Günsche then entered the room, surveyed the scene and left shortly afterwards to declare to those waiting outside that the Führer was dead. Preparations had already been made to dispose of the bodies of Hitler and his wife as Hitler had made sure that Günsche understood that on no account was his body to be found intact by the Soviets. A few hours before Hitler killed himself Günsche had telephoned the Reichs Chancellery garage and spoken to Hitler’s principal driver, Erich Kempka. Günsche ordered Kempka to bring over a large quantity of petrol. ‘I was…to ensure that five cans of gasoline, that is to say 200 litres, were brought along,’ recalled Kempka. ‘I at once took along two or three men carrying cans. More were following, because it took time to collect 200 litres of gasoline.’ The cans were left near the bunker’s emergency exit.

Mark standing just outside the bunker’s emergency exit in April 2016, through which the bodies of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun were brought outside to be cremated on 30 May 1945.

The same view in 1945. Mark would be standing just in front of the doorway on the left

Closer shot of the Bunker Emergency Exit, with an American officer passing Red Army sentries, showing the narrow metal staircase leading down to the Führerbunker.

Closer shot of the Bunker Emergency Exit, with an American officer passing Red Army sentries, showing the narrow metal staircase leading down to the Führerbunker.

Hitler’s body was wrapped in a blanket and carried up the stairs to the bunker’s emergency exit by Linge, SS–Hauptsturmführer Ewald Lindloff and SS-Obersturmführer Hans Reisser of the SS-Begleit-Kommando, and SS-Obersturmbannführer Peter Högl, deputy commander of the RSD. Bormann carried Eva Hitler’s body upstairs. Once outside, the SS officers placed both of the bodies, still wrapped in grey blankets, into a shell crater and then doused them liberally with petrol. An attempt was made to light the petrol, but it was unsuccessful. Linge went back into the bunker and returned with a thick roll of papers. Bormann lit the papers and threw them into the hole, the petrol igniting with a whoosh. Others had joined them. Standing just inside the emergency exit door Günsche, Bormann, Högl, Linge, Lindloff, Reisser, Kempka and Goebbels raised their arms in the Nazi salute. But the party was soon driven inside as Soviet shells began to land in the Reichs Chancellery garden.

Mark pointing at the shell hole where Hitler and Eva Braun’s bodies were burned in the Reichschancellery’s Wintergarten.

The same place in May 1945. The shell hole is visible at the bottom left of the photograph.

Another view of the shell crater where the bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun were burned.

Another view of the shell crater where the bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun were burned.

The shattered rear of the Reichs Chancellery facing on to the formal gardens above the Hitler’s lower bunker. This wall was directly behind the Bunker emergency exit. The Vorbunker (or Upper Bunker) was beneath this building.

The same view looking the opposite direction in 2016. The Reichs Chancellery’s rear would have roughly corresponded with the modern pavement and dirt tracks beside the low wooden fence above.

Thirty minutes after the cremation of Hitler and his wife was begun, Günsche ordered Lindloff to go out and see how it was progressing. Lindloff reported that both bodies were charred and had burst open. He also said that they had been damaged by shellfire. During the afternoon, SS-Begleit-Kommando guards continued to add jerry cans of fuel to the burning hole in between the Soviet barrages.

A closer view of the site of the shell hole where Hitler and Eva Braun’s bodies were burned.

At 4.15pm Linge ordered SS–Untersturmführer Heinz Krüger and SS-Oberscharführer Werner Schwiedel to roll up the bloodstained rug from Hitler’s study, carry it up to the Reichs Chancellery garden and burn it. At 6.30pm Lindloff reported to Günsche that he and Reisser had disposed of the remains. It appears that from the remains later found by the Soviets some days later that the bodies of Hitler and his wife were burned beyond recognition and possibly damaged by shellfire, if indeed they were the mortal remains of the tyrant and his spouse.

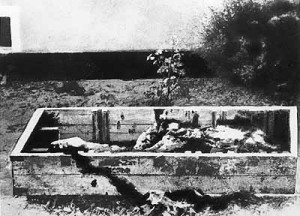

A Soviet ammunition crate said to contain the charred remains of Hitler. This is the only photograph that the Russians have released that claims to show Hitler’s corpse. No photographs from his autopsy have been made public. In contrast, there are numerous Red Army photos of Dr. Goebbels’ partially cremated body, both at the Bunker site and in a pathology laboratory.

A Soviet ammunition crate said to contain the charred remains of Hitler. This is the only photograph that the Russians have released that claims to show Hitler’s corpse. No photographs from his autopsy have been made public. In contrast, there are numerous Red Army photos of Dr. Goebbels’ partially cremated body, both at the Bunker site and in a pathology laboratory.

Although Hitler was dead, the business of government continued as well as the defence of the remaining areas of the government quarter by Hitler’s bodyguard units and associated troops. Hitler’s Last Will and Testament had broken up the position of ‘Führer’ into three separate offices. Goebbels was named Reichs Chancellor; with Grossadmiral Dönitz appointed Reich President and Bormann made Party Minister.

But at this stage, only Dönitz could exercise any limited control from Flensburg in the north. Goebbels made it very clear that he and his wife Magda would emulate their beloved Führer and commit suicide when the time came.

On 1 May Chancellor Goebbels drafted a letter to the Soviets and ordered 47-year-old General der Infanterie Hans Krebs, Chief of the Army General Staff (OKH), to deliver it under a white flag of truce to General Vasili Chuikov, commander of the 8th Guards Army which was occupying central Berlin. The letter informed the Soviet High Command of Hitler’s death, the appointment of Goebbels as Reich Chancellor and his offer of a cease-fire. When Krebs was sent packing with the clear instruction that the Soviets would only accept unconditional surrender, Goebbels knew that it was futile to continue. Later that day Vizeadmiral Hans-Erich Voss and almost a dozen other military officers arrived at the Führerbunker to say farewell to Goebbels as their supreme commander.

At 8pm that evening Goebbels instructed dentist SS-Sturmbannführer Helmut Kunz to drug his six children with morphine. Then Hitler’s personal physician, SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Ludwig Stumpfegger, crushed a vial of cyanide in each of their jaws, killing them.

A little while later a subdued Goebbels pulled on his gloves and hat, and arm-in-arm with his wife, climbed the stairs to the bunker’s emergency exit and emerged into the Reichs Chancellery garden. His adjutant, 29-year-old SS-Hauptsturmführer Gunther Schwägermann, followed him. (Historical Footnote: at the time of writing in 2016 Schwägermann remains alive, aged 101. He is certainly the last living witness to the events in the Bunker, but has refused to give any interviews.)

Schwägermann went to collect more petrol to burn the Goebbels’ bodies while Goebbels and his wife went around the corner out of sight. Schwägermann said that he heard a pistol shot and came upon his master and Magda Goebbels dead. She had taken poison while Goebbels had shot himself in the head. Schwägermann ordered the SS-Begleit-Kommando sentry at the bunker emergency exit to shoot Goebbels again in the head to make sure – Schwägermann could not face doing so himself. The two men then poured petrol over the bodies and set fire to them. Unfortunately, there was insufficient petrol remaining to burn the bodies and the fire-blackened corpses remained easily recognizable to Voss when he was forced by the Soviets to identify them the following day. The shape of Goebbels’ head and jaw as well as his leg brace were unmistakable, along with the remains of his brown Nazi uniform and Golden Party Badge.

Dr. Goebbels’ charred corpse

Between 1945 and 1949 the Soviets levelled the battle-damaged Old and New Reichs Chancelleries. A failed attempt was also made to destroy the Führerbunker. Because the site was close to the Berlin Wall, it remained essentially untouched until the late 1980s when East Germany built residential housing units and a new road system over the site. In 1988 the Vorbunker was torn out. The massive roof of the Führerbunker was broken up and allowed to fall into the rooms below before it was buried under a nondescript car park. So, the Führerbunker still exits, buried beneath modern Berlin, its historical significance marked only by a small information board erected on the site in 2006.

As for the New Reichs Chancellery building, this was knocked down by the Soviets shortly after the war. However, some of the marble panels that once lined the huge reception halls were used to refurbish Mohrenstrasse U-Bahn Station, the entrance to which is just across the street from the site of Hitler’s bunker and though rather shabby and dirty, the huge blocks of marble cover the walls and pillars. Here are some pictures: