ESCAPE FROM SOBIBOR

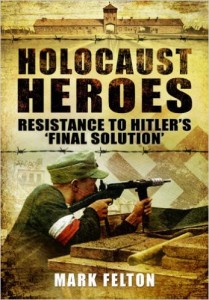

For more dramatic stories like this check out Mark’s book Holocaust Heroes

‘We knew our fate. We knew that we were in an extermination camp and death was our destiny. We knew that even a sudden end to the war might spare the inmates of the ‘normal’ concentration camps, but never us. Only desperate actions could shorten our suffering and maybe afford us a chance of escape. And the will to resist had grown and ripened.’

Thomas Toivi Blatt, Sonderkommando Sobibor

The small group of Jewish prisoners inside the camp tailor’s shop exchanged fearful glances, as the sound of hooves grew louder outside. One of them quickly peeked out of one of the hut’s small windows.

‘He’s arrived,’ he muttered. ‘Get ready.’

A few seconds later and the hut door opened and in stepped SS-Untersturmführer Johann Niemann, the 30-year-old deputy commandant of the Sobibor Extermination Camp. Outside, another prisoner held the bridle of Niemann’s chestnut horse that he used to ride imperiously around the camp. Niemann tucked his riding crop under one armpit and began to slowly remove his gloves, his hard eyes moving around the room and settling momentarily on each of the Jewish faces before him. The prisoners took in Niemann’s uniform and shuddered. A devil walked among them, the SS death’s head badge grinning at them from Niemann’s cap band and from his right collar patch. As a concentration camp officer in the notorious SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV) Niemann did not wear the twin lightning flash runes of the Waffen-SS on his collar. His rank was indicated by three silver pips arranged in a diagonal line on his left collar patch and army-style silver shoulder straps. The prisoners glanced at his waist, where his black belt with its silver SS buckle supported a leather holster. Inside sat Niemann’s Luger pistol, ready for instant use against any ‘problem’ prisoners.

One of the tailors brought out an unfinished officer’s uniform ready for Niemann to try on. After removing his belt and tunic, the prisoners were helping him into the new jacket when Niemann sensed movement behind him. He turned his head to one side and managed to mutter ‘Was?’ before Soviet prisoner-of-war Alexander Shubayev buried a homemade hatchet in his skull. Niemann didn’t scream, just grunted at the impact, which killed him instantly. He collapsed onto the hut’s wooden floor, dark rivulets of blood running across its dusty surface from the gaping wound in his head. One prisoner picked up Niemann’s heavy gun belt and drew the Luger from its holster. It felt solid and cold in his grasp. He looked at his comrades and nodded slowly. The Sobibor Revolt had commenced.

Beginning in 1940, the Nazis had established sixteen labour camps in the Lublin region near the village of Sobibor. It was intended that the Jews sent to these camps would work as agricultural labourers under German colonial overseers. Over 95,000 Jews expelled from Warsaw and Vienna were shipped in for this task, and paid for their labour. They were housed in a network of subcamps based on the Concentration Camp at Krychow.

Sobibor Camp was constructed by SS-Hauptsturmführer Richard Thomalla between March and April 1942, using Jewish Sonderkommando labour after German policy towards the Jews had dramatically changed. The location, marshy woodland with a sparse population, was chosen because it was close to the rail line that ran between Chelm and Wlodawa connecting the General Government with Reichskommissariat Ukraine. The garrison would consist of a German commandant, initially SS-Obersturmführer Franz Stangl, 29 SS non-commissioned officers, and between 90 and 120 Ukrainian SS auxiliaries, or “Trawnikis” after the concentration camp where the ex-Red Army prisoners-of-war were trained. At the end of August 1942 a new commandant was appointed after Stangl was moved to take command at Treblinka, SS-Hauptsturmführer Franz Reichleitner.

An Austrian, Reichleitner had been born in 1906 and was another Aktion T4 veteran. At the Hartheim Institute, Reichleitner had worked alongside Franz Stangl under the command of Christian Wirth. The prisoners at Sobibor regarded Reichleitner as an austere figure who was always immaculately turned out in his uniform, and always wore gloves. He had very little to do with the Jews, relying on his trusted second-in-command Niemann and a coterie of efficient SS-TV sergeants and corporals. But it was obvious that Reichleitner was feared and respected by the other SS.

Sobibor was small compared with Auschwitz or Dachau, consisting of three camps, surrounded by a barbed wire fence into which tree branches had been woven. Trees had also been planted around the camp’s perimeter to further shield it from public view and it was also surrounded by a deep water-filled moat. Camp I, under the command of SS-Oberscharführer Karl Frenzel consisted of the main administration offices, housing for the German SS and Trawnikis auxiliaries, and barracks for a large detachment of Jewish Sonderkommandos. Here also was the prisoners’ kitchen.

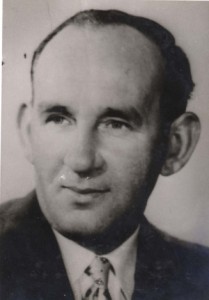

Karl Frenzel

Thirty-two-year-old Frenzel had been active with the Nazis since 1930 when he had enlisted in the SA. When war broke out in 1939, Frenzel had been drafted into the Reich Labour Service but soon after released to help take care of his five children. Desperate to take part in the war effort, Frenzel volunteered through his SA connections and was recruited into the SS-TV and was assigned to the highly secret Aktion T4.

The T4 euthanasia programme that was partly based at Schloss Hartheim in Austria was the bloody prelude to the industrialized murders that were to follow in places like Sobibor and Treblinka II. The mentally retarded and physically disabled were murdered on the recommendations of doctors as the Nazis attempted to remove all ‘defectives’ from their population. Over 70,000 ‘patients’ were to die during the course of the programme, which continued in operation until just after the war ended in 1945. Told that the killings were the responsibility of doctors, Frenzel, Stangl, Reichleitner and the other SS-TV men had set aside their moral reservations and done their duty, as they conceived of it. Frenzel’s primary job was removing bodies from the small gas chambers, wrenching out any gold teeth and then burning the bodies in the crematoria.

On 20 April 1942 Frenzel was assigned to Sobibor, where he was widely detested and feared by the prisoners, and was known for using his whip on them frequently. In one notorious incident in spring 1943, two Jews from Chelm were caught trying to escape from Sobibor. Frenzel decided, in consultation with the other SS senior NCOs, that an example should be made. At roll call every tenth Jew was taken out of the line to be shot, twenty being murdered in this way. Following this escape attempt, a minefield was laid around the outside of the camp’s perimeter as a further deterrent.

Camp II, or the Vorlager, consisted of the railway platform where evacuation trains were off-loaded, a ramp, the undressing barracks and warehouses where 400 of the Jewish Sonderkommandos worked. They sorted and stored property confiscated from Jews that arrived by train at the camp platform. There was also a building where the newly arrived Jews had their heads shaved, and their valuables taken from them before they proceeded into Camp III and the gas chambers.

Camp III contained a further Sonderkommando unit’s barracks, these men tasked with the open-air cremation of the bodies of the dead and the disposal of these bones and ashes in large pits.

The evacuation trains that brought the Jews to Sobibor consisted of between forty and sixty freight cars. The platform in Camp II was large enough to permit the unloading of twenty cars at a time. On arrival, the SS told the Jews that the facility was a transit camp, where they would be disinfected for lice and processed through to working parties in labour camps elsewhere. ‘I helped Jews out of the trains with all their baggage,’ said Sonderkommando Philip Bialowitz. ‘My heart was bleeding knowing that in half an hour they would all be reduced to ashes. I couldn’t tell them. I wasn’t allowed to speak. Even if I told them, they wouldn’t believe they were going to die.’

Fresh arrivals were met by SS NCOs whose welcome speech was designed to make the Jews cooperate in their own destruction. ‘The Jews of Warsaw, your attention!’ one of the SS would shout along the length of the platform. ‘You are in a transit camp from which you will be sent to a labour camp. As a safeguard against epidemics you must immediately hand over your clothing and parcels for disinfection. Gold, silver, foreign currency and jewellery must be placed with the cashier, in exchange for a receipt. These will be returned to you at a later time upon presentation of the receipt. For bodily washing before continuing with the journey all arrivals must attend the bathhouse.’

Some of the new arrivals would be hived off into the ranks of the Sonderkommandos to replace those who had died from disease, exhaustion or murder. In this way, tens of thousands of people arrived at the railway platform in front of the camp with no idea of what awaited them.

The main deportations to Sobibor were made between May 1942 and autumn 1943. The Jews came primarily from the ghettos of the General Government, with others from the Soviet Union, Germany, Austria, Slovakia, Bohemia and Moravia, Netherlands and France. Altogether, upwards of 170,000 people entered Sobibor.

The events that led to a Sonderkommando rising at Treblinka had their roots elsewhere. Rumours arrived in Sobibor that most of the 600 Sonderkommando workers would soon become surplus to requirements and that the Germans planned to kill them. The reason for this was that another Aktion Reinhard death camp at Belzec had been closed and dismantled, the Germans shooting the remaining Sonderkommandos. The Sonderkommandos realised that the same thing would probably happen at Sobibor as the number of evacuation transports had noticeably slowed. The Jews needed a plan of action to save themselves. ‘We started organising and talking and it gave us something to live for again,’ said Esther Raab, a female prisoner. ‘[The idea] that maybe we’ll be able to take revenge for all those who can’t.’

The leader of the Jews in Sobibor was the 33-year-old son of a Polish rabbi named Leon Feldhendler. He had been head of the Judenrat in his home village of Zolkiewka in Lublin. With a hardcore of conspirators, Feldhendler considered several possible avenues of escape. The initial plan was to poison the SS and seize their weapons. But vigilant SS guards discovered a secret batch of poison and five Jews were shot in retaliation. Another plan was to set fire to the camp and try and escape during the subsequent confusion. But the mining of the camp perimeter by Wehrmacht engineers following the attempted escape of two Jews made such a plan extremely risky. The plan was eventually rejected as impractical. What Feldhendler and his fellow plotters lacked was organizational ability and who better to possess those skills than soldiers? The answer to Feldhendler’s problems was the arrival at Sobibor on 23 September 1943 of a man called Sasha.

Lieutenant Quartermaster (Class II) Alexander “Sasha” Pechersky was a 34-year-old Jewish Red Army officer who had been captured during the Battle of Moscow in 1941. The son of a lawyer, Sasha was born in the Ukraine, gained a degree in music and literature in Rostov and was working as an accountant and manager of a small music school when he was conscripted into the Red Army as a Junior Lieutenant on 22 June 1941, the day the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa. Promoted to Lieutenant in September 1941, Sasha was captured in October at the city of Vyazna. He suffered seven months of typhus before escaping with four other POWs in May 1942. Recaptured the very same day, Sasha was sent to a penal camp in Belorussia, then to another harsh camp near Minsk. During the routine medical examination it was revealed that he was circumcised and Sasha immediately admitted to being a Jew. On 20 August 1942 he was separated from non-Jewish prisoners-of-war and sent to an Arbeitslager in Minsk. On 18 September 1943, 2,000 Minsk Jews, including 100 Jewish Red Army POWs, were herded on to a cattle train and sent to Sobibor, arriving on the 23rd. Sasha was among eighty Jews selected to join the Sonderkommando in Camp II. The sudden and unexpected arrival of prisoners who were trained soldiers provided the conspirators with a considerable morale boost. Perhaps these Russians could help?

Sasha also made an impression on the SS quite early on. He was clearly a man who commanded respect among his peers, and also a proud military officer and no mere slave. Three days after his arrival, Sasha was outside the camp on a working party that was chopping up tree stumps. In command of the party, which was guarded by a detachment of SS–Trawnikis, was SS-Oberscharführer Frenzel. Impatient at the exhausted manner in which the Jews were tending to their tasks, Frenzel had decided to punish certain workers with twenty-five lashes from his whip. Frenzel noticed that Sasha had stopped work during one of these ‘punishments’.

‘Russian soldier,’ shouted Frenzel, ‘you don’t like the way I punish this fool? I give you exactly five minutes to split this stump.’ Frenzel kicked a large tree stump with the toe of his black jackboot. ‘If you make it, you get a pack of cigarettes. If you miss by as much as one second, you get twenty-five lashes,’ said Frenzel, a cruel smile creasing his face.

Sasha attacked the stump with his axe like a madman, Frenzel timing him with his watch. He finished in four-and-a-half minutes. Frenzel, his face a mask of anger, proffered a pack of cigarettes. ‘Thanks, I don’t smoke,’ said Sasha. Frenzel, muttering under his breath, stalked off while the other prisoners continued chopping, astonishment drawn across their sweaty faces. They were even more surprised when Frenzel returned with a lump of bread and some margarine and offered them to Sasha. The big Red Army officer shook his head slowly. ‘Thank you, the rations we are getting satisfy me fully.’ Frenzel’s face turned beetroot red, his fist tightening around his whip handle. He stared at Sasha for a moment, clearly debating in his mind what he should do, while Sasha ignored him and returned to chopping wood. Frenzel once again stalked off. The incident deeply impressed the other members of the working party and that night the proud defiance of the Soviet officer was the talk of the Sonderkommando barracks in Camp I.

It was obvious that the resistance organisation desperately needed someone like Sasha and Feldhendler reached out to him on 29 September. He hoped that Sasha might be able to contact the partisans, many of whom were escaped Soviet POWs, to enlist their aid in liberating the Sobibor Jews. But Sasha was unequivocal in his response. ‘The partisans have their own tasks,’ replied Sasha to Feldhendler, ‘and no one can do our work for us.’ The meaning was clear – if the Jews wanted out of Sobibor, they would have to do all the work themselves. Some of Sasha’s fellow Soviet prisoners were already exploring an escape from the camp, but only for themselves. They were reluctant to let untrained and disorderly foreign civilians join them. But Feldhendler countered that if the Soviet POWs managed to escape the SS would retaliate against the innocent Jewish civilians left behind in the camp. He managed to convince Sasha that any escape should include everybody.

It was decided that it would be better from a security standpoint if the Germans did not see Sasha and Feldhendler constantly meeting. Instead, a young Jew named Shlomo Leitman would act as a go-between for the two leaders. Sasha and his men carefully gathered intelligence on the layout of the camp, the number of guards and their personalities, routines and armament, as well as the all-important perimeter defences. In this, the Jewish civilian members of the Sonderkommando proved invaluable, having been imprisoned in Sobibor for much longer than the Soviets.

The first plan proposed by Sasha was a tunnel. Digging began in early October 1943 beneath the carpenter’s workshops in Camp II. On 7 October, Sasha became very concerned. It was clear that there weren’t enough hours of darkness for all of the camp’s prisoners to successfully pass through the long tunnel to freedom, and he knew that the non-military backgrounds of the civilian workers would probably lead to arguments and fights breaking out amongst those waiting to go. Before Sasha was forced to call off the tunnel break, the diggings were destroyed by two days of very heavy rain on the 8 and 9 October. It was back to the drawing board.

The second plan was a much more dangerous proposition – a revolt. This would involve attacking and overpowering the guards and seizing the camp. Though this appeared to be a tall order, Sasha believed that the key to the plan’s success was to remove the German brain from the larger SS body – that was, to kill the small number of German SS-TV officers and NCOs that administered the camp. It was the same conclusion that was reached by the desperate resisters at Treblinka II. Sasha believed that if the prisoners succeeded, the remaining Ukrainian SS guards would be confused and possibly open to negotiations. If all else failed, the prisoners could fight them with weapons captured off the dead guards, or they could try to storm and capture the camp’s armoury. It was known that the Trawnikis were not completely trusted by the regular SS, and only issued with limited ammunition for their weapons. The gravity of what the prisoners were planning to do was not lost on any of them for a second. ‘We had no dreams of liberation,’ said Thomas Toivi Blatt, ‘we hoped merely to destroy the camp and to die from bullets rather than from gas. We would not make it easy for the Germans.’

The Trawnikis that provided the bulk of the guards in the camp were armed with five-shot bolt-action Mauser 98K rifles, the standard German infantry weapon of the Second World War. The guard towers also contained MG42 machine guns, extremely rapid firing and highly effective belt-fed weapons. The SS-TV men were routinely armed with Luger or Walther P38 semi-automatic pistols and had access to Schmeisser MP40 machine pistols. In response, Sasha asked the prisoners to begin manufacturing large knives and small hatchets. These would be used to dispose of as many of the German SS NCOs as possible in a series of carefully planned ambushes.

The Trawnikis were even more strongly despised than the Germans. ‘We were terrified of the Ukrainian guards at Sobibor,’ said Blatt. ‘They were worse than the Germans. They mistreated us; they shot the old and the sick new arrivals who couldn’t walk anymore. And they were the ones who drove the naked people into the gas chambers with their bayonets.’ Blatt’s job involved cleaning SS boots. ‘They would come back with splashes of blood on their boots. I often had to work a few feet away. If they [the Jews] refused to go on, they hit them and fired shots. I can still remember their shout of ‘Idi suida’, which means ‘come here.’’

Camp commandant SS-Hauptsturmführer Reichleitner left on leave shortly before the revolt. On 12 October, the hated and feared senior SS-TV NCO in the camp, SS-Oberscharführer Gustav Wagner, also departed on leave. This was a great relief to everyone. The tall, blond and sadistic Wagner was known to be exceptionally cunning and unrelenting in his efforts to uncover subversive activity among the Sonderkommandos. ‘Wagner’s departure gave us a tremendous morale boost,’ said conspirator Thomas Toivi Blatt. ‘While cruel, he was also very intelligent. Always on the go, he could suddenly show up in the most unexpected places. Always suspicious and snooping, he was difficult to fool. Besides, his colossal stature and strength would make it very difficult for us to overcome him with our primitive weapons.’

With Reichleitner and his chief guard dog Wagner gone, Sasha ordered that the final revolt plan be ready by the end of 12 October. The Soviet POWs were dispatched singly to each of the huts where an ambush killing was to be perpetrated in order to stiffen the resolve of the resisters and to do the actual killing if necessary. Each hut had organised a ‘combat team’ consisting of about three men, with their knives and hatchets carefully concealed. The targeted German officers and NCOs would be lured singly into the huts and then dispatched. Lures included appointments for uniform or boot fittings, or to peruse expensive coats taken from recent transports. ‘The planning took into consideration the German’s brashness and power-hungry mistreatment of the seemingly subdued Jews,’ said Blatt, ‘their consistent and systematic daily routine, their unfaltering punctuality, and their greed.’

The targets were carefully selected. The most important was deputy commandant SS-Untersturmführer Johann Niemann. In the absence of Reichleitner on leave, Niemann was acting commandant of the camp. Born in 1913, Niemann had joined the Nazi Party in 1931 and the SS in 1934. He had served at another Aktion Reinhard camp, Belzec, as an Oberscharführer, commanding Camp II. Transferred to Sobibor, Niemann was commissioned as an officer after Heinrich Himmler’s visit to the camp on 12 February 1943. According to Karl Frenzel, Niemann was a brutal officer. ‘A Polish Kapo [Jewish worker appointed to oversee other Jews] told me that some Dutch Jews were organising an escape, so I relayed it to Deputy Commandant Niemann. He ordered the seventy-two Jews to be executed.’ The Jews were also aided by the fact that almost a dozen SS NCOs were away from the camp on leave when the revolt was launched.

The method for killing the SS was to be as quiet as possible. They were to be axed in the skull or stabbed to death and their bodies quickly hidden. X-day, the day the revolt would be launched, was set for 13 October. But in the morning, Sasha and the rest of the plotters were disconcerted by the sudden arrival in the camp of a company of SS men. There was much confusion among the prisoners, who initially feared that their plot had been discovered and the extra manpower brought in to deal with them. But instead the SS piled out of their trucks and started eating and drinking with the Sobibor SS-TV men in the main canteen. As the extra SS were still in the camp at lunchtime, Sasha decided to postpone the revolt until the following day. Later in the afternoon, the visiting SS company packed up and drove away.

On 14 October everyone was ready. It was now or never. At noon, each battle team commander secretly met with Sasha for final instructions. There was one nasty moment when Frenzel marched into the carpentry shop and noticed that one of the prisoners was dressed in his best clothing. The prisoners had gathered their few possessions ready for the revolt. Unlike Wagner, who would undoubtedly have become suspicious, Frenzel instead sarcastically asked the man whether he was off to a wedding.

At 2pm, SS-Unterscharführer Walter Hochberg, who was not on the target list to be killed, suddenly entered Camp I armed with an MP40 machine pistol. This was unusual, as the SS-TV men rarely carried such firepower. Hochberg took away four prisoners. Sasha discovered that Hochberg was so armed because he hadn’t had with him because of the recent leaves a Ukrainian Trawniki as backup. By 4pm the battle teams were ready and in position.

The first to die was acting commandant Niemann. Once he was dead, his body was quickly dragged into a hiding place and the blood cleaned up. The officer’s loaded Luger pistol was added to the resisters’ meagre stash of weapons. Another prisoner led Niemann’s horse back to the camp stables to complete the illusion of normality.

SS-Scharführer Josef Wolf entered a storeroom shortly after 5pm, lured there by the offer of a nice coat that the prisoners had taken off a transport. As one prisoner helped Wolf into the coat, two others quickly pulled out hatchets and drove them into Wolf’s head, killing him. His body was carefully concealed beneath a pile of clothes, his blood mopped up and his pistol taken. Close by, 33-year-old SS-Oberscharführer Rudolf Beckmann, the head of sorting commands in Camp II, was lured towards a storeroom to view a leather coat. But Beckmann suddenly changed his mind and strode off to his office instead. A little later a combat team entered his office and stabbed him to death with knives. His body was left in a pool of blood on the floor behind his desk.

SS-Unterscharführer Walter Hochberg suddenly appeared in the SS garage and was there killed by the momentarily surprised Jewish prisoners. A major target was the commandant of Camp II, SS-Oberscharführer Göttinger. He was lured into the Shoemakers’ Shop to try on some new jackboots. As he leaned over he was struck in the head with a hatchet and killed.

The NCO in charge of the Ukrainian guards, 27-year-old SS-Oberscharführer Siegfried Graetschus, entered the Shoemakers’ Shop and was axed in the head by Soviet POW Arkady Wajspapir. Soon after, SS-Mann Ivan Klatt, one of the Trawnikis, came into the Shoemakers’ Shop looking for Graetschus, and he was similarly dispatched, his Mauser rifle being added to the pistols that the Jews had now procured from the dead SS. Jews also cut the camp’s telephone and electricity cables to prevent the remaining SS from calling in reinforcements. SS-Scharführer Friedrich Gaulstich was killed in the Carpentry Shop, while SS-Unterscharführer Ernst Stengelin was also dispatched without trouble. So far, everything was progressing perfectly to plan. The alarm had not been raised and the SS were none the wiser.

Around 5pm, the camp prisoners, most of whom had little idea that a revolt was underway, began to assemble on the Appellplatz, the area the Germans used for roll call parades. At 5.10pm Sasha blew an SS whistle, used to summon the prisoners to attention. It was twenty minutes early and the bemused prisoners turned and stared as Sasha stood to address them. ‘Our day has come,’ he shouted. ‘Most of the Germans are dead. Let’s die with honour. Remember, if anyone survives, he must tell the world what has happened here.’

At this point shouting was heard – a Ukrainian guard had discovered the bloody corpse of SS-Oberscharführer Beckmann lying behind his desk. The guard ran out shouting ‘A German is dead!’

Sasha didn’t hesitate and shouted ‘Forward, comrades!’ at the top of his voice. Someone behind him yelled ‘Forward!’ while several others screamed ‘For the Fatherland!’ or ‘For Stalin!’ Although the Jews had managed to kill a total eleven SS men, plus a few of the Trawnikis, Frenzel and the remaining SS quickly armed themselves with Schmeisser machine pistols and opened fire on the prisoners as they attempted to storm the wire.

The prisoners fired back at the Trawnikis manning the gates and guard towers, killing or wounding several, while hundreds flung themselves at the fences, and began to clamber over. The assault on the arms store failed, machine gun fire barring the way. ‘Most of the people who were escaping turned in the direction of the main gate,’ said Sasha. ‘There, after they finished off the guards, under cover of fire from the rifles that a few of them had…[they] broke through the gate and hurried in the direction of the forest.’

‘We rushed to the fence,’ said Philip Bialowitz. ‘We were shooting back as the men in the guard towers were shooting at us with machine guns.’

‘We ran out of the workshop,’ recalled survivor Ada Lichtman. ‘All around were the bodies of the killed and wounded. Some of them were exchanging fire with the Ukrainians, others were running toward the gate or through the fences.’ The SS opened a vigorous fire, shooting down people as they ran or climbed. Many people were killed after getting over the wire when they stepped on landmines. In horrific scenes, hundreds of survivors, many wounded, charged for the forest with German bullets stitching the earth around them.

‘We ran through the exploded mine field holes,’ said Thomas Blatt, ‘and we were outside the camp. Now to make it to the woods ahead of us. It was so close. I fell several times, each time thinking I was hit. And each time I got up and ran further…100 yards…50 yards…20 more yards…and the forest at last. Behind us, blood and ashes. In the greyness of the approaching evening, the towers’ machine guns shot their last victims.’

Once in the forest and out of range of the guards, the survivors searched around desperately for friends and relatives before striking off in large groups. But these large groups eventually broke up into smaller and smaller groups as the pressures of searching for food and water took its toll. Sasha initially led a party of about fifty survivors. But on 17 October, he halted the group in the forest and selected several men. They were all armed with Mauser rifles taken from the Trawnikis. Sasha only left one rifle with the main group. Though the people protested at his decision to leave on what he said was a ‘reconnaissance’, they couldn’t stop him and he promised to come back for them. He never did. Sasha, as a soldier, probably realised that trying to feed and protect such a large group was foolhardy, so he took a hardcore of armed men and struck out on their own, giving them a better chance of making it. Some Sobibor survivors never forgave Sasha for abandoning them in the forest in this way.

An estimated 158 Jews were killed by the guards during the revolt, or blown up by mines. The SS, Wehrmacht and Order Police murdered a further 107 during hunts for the escapees. Another 53 died from other causes before the end of the war. There were only 58 known survivors (48 men and 10 women) from Sobibor.

After the revolt the SS decided to close down killing operations at Sobibor. Camp III was disassembled and the remaining Sonderkommandos shot. Furious that the revolt could even have occurred, the SS took further revenge measures against the Jews that were under their control, culminating in the murders of 42,000 in Lublin District three weeks after the revolt in an operation codenamed ‘Erntefest’. The Germans had plans to use the remainder of Sobibor Camp for other purposes, and although they based a small guard detachment of Trawnikis at the site until March 1944, the camp never held any more prisoners.

Leon Feldhendler hid in Lublin until the end of the German occupation in July 1944. He was shot dead in his flat on 2 April 1945 in mysterious circumstances – possibly murdered by a rival Zionist group or the victim of a robbery gone wrong. Thomas Toivi Blatt was initially hidden by a Polish farmer after the escape, but was later shot and wounded by this same farmer. Blatt survived the war, moving to Israel and then the United States. He wrote the book ‘Escape from Sobibor’ in 1983, seeing it turned into a successful film, and two further books on the camp. He is one of a tiny handful of survivors who is still alive and lives in Santa Barbara, California.

Sasha joined the Soviet partisans, sabotaging railway lines, cutting telephone wires and conducting hit-and-run attacks on the Germans. Once the Red Army had occupied Poland, Sasha, like all other Red Army soldiers who had been taken prisoner by the Nazis, was punished on Stalin’s order. He was conscripted into a tough penal battalion and sent to the front. But Sasha’s commanding officer was so shocked by Sasha’s story of what happened at Sobibor that Sasha was sent to Moscow where he spoke before a commission of inquiry. Promoted to captain, Sasha was decorated for gallantry and finally discharged after suffering a foot injury. The Soviets refused to allow him to testify before the Nuremberg Trials and in 1948 Sasha was arrested during a campaign against ‘disloyal Jews’. Stalin’s death in 1953 saved Sasha from further suffering, and he was released. He worked in a small amateur musical theatre. Refused permission by the Soviet authorities to testify at the Eichmann Trial in Jerusalem in 1960, Sasha died in 1990.

Commandant Karl Reichleitner was transferred to Trieste and Fiume in Italy along with nearly all the Aktion Reinhard death camp personnel where they formed a special SS unit, Sondertruppe R, detailed to fight partisans and murder Jews. Reichleitner was killed at the age of 37 by partisans on 3 January 1944.

For more stories like this check out Mark’s forthcoming book Holocaust Heroes