The Führersonderzug pulled into Giessen Station in the German state of Hesse, a small, pretty town of large half-timbered houses. There were no adoring crowds awaiting the Führer – instead the platform was carefully guarded by SS. Outside, in the station courtyard stood a fleet of polished midnight-blue Mercedes-Benz limousines and more SS-Begleit-Kommando guards. Hitler stepped slowly down from his Pullman carriage, a black cape over his uniform tunic. It was blustery and cold and the Fuhrer, walking with a slight stoop, headed straight for his car where Erich Kempka, his personal driver for so many years, sat waiting, the engine running. Hitler’s entourage settled themselves into the fleet of cars, turning up their collars against the cold wind. Twenty minutes later the procession of gleaming vehicles swept uphill through the tiny village of Ziegenburg towards a large, gloomy Gothic castle that stood on a hill above the houses, perched atop a lofty promontory. It was 11 December 1944 and Hitler had arrived at the Adlerhorst (Eagle’s Eyrie), his top secret Western Front headquarters. He was happy and excited, for he came with a new plan prepared that he hoped would win him a great victory against the Western Allies. As his car entered a narrow approach tunnel to Ziegenberg Castle, Hitler felt energized. As he stated to his generals that evening: ‘If forced back on the defensive, it is all the more important to convince the enemy that victory was not in sight.’ At the Adlerhorst he would change the course of the war back into Germany’s favour.

Hitler would have several military headquarters for his campaigns in Western Europe. They were built and used during three specific periods: the German invasion of France and the Low Countries during 1940; the Allied invasion of Normandy in 1944; and the Ardennes Offensive of 1944-45. Hitler spent most the war, over 800 days, at the Wolf’s Lair in East Prussia demonstrating that his strategic focus was primarily upon the monumental fight with the Soviet Union. When not at the Wolf’s Lair he was mostly to be found at his private house, the Berghof, in southern Bavaria. Because of this, his visits to the Western Front were often short affairs. But a considerable amount of money, effort and time was expended in finding and creating suitable headquarters for Hitler and his large entourage, the most significant but perhaps least known of the Führer Headquarters being the Eagle’s Nest in western Germany, hidden as with most of Hitler’s HQs in a gloomy forested area with more than an element of the Brothers Grimm about the place.

On 10 October 1939 Hitler’s first FBB commander, Irwin Rommel, was sent West to find a suitable location for a new Fuhrer Headquarters for the forthcoming campaign against France and the Low Countries. Hitler also dispatched his architect Albert Speer along with the Reich Minister for Armaments and Ammunition, Dr. Fritz Todt, to help with the search.

Speer and Todt recommended Ziegenberg Castle in Langenhain-Ziegenberg, 22 miles (35km) from Frankfurt-am-Main. The castle, looking like something out of a fairytale, sits in the densely wooded Taunus Mountains and was codenamed ‘A’ for ‘Adlerhorst’ (Eagle’s Eyrie) by the Nazis. Originally constructed in the 12th century, the castle had fallen into disrepair by the mid-19th century.

(Kransberg Castle, near Ziegenberg, was also to be utilised as part of the Adlerhorst complex)

This was to be Hitler’s showpiece headquarters for the campaign in the West and no expense was spared. Incredibly, the local villagers who lived below the Castle in Ziegenberg do not appear to have realized that it was now a Führer Headquarters. The Germans kept the secret well, using labour that was brought into the area to complete the building work. As far as locals were concerned, Ziegenberg Castle was just another military installation during a time of war. The castle was extensively renovated and seven concrete bunkers that were disguised as half-timbered cottages were built nearby at Wiesental. These were connected with extensive underground bunkers in turn were themselves connected with the main castle by tunnels.

Another local castle, Schloss Kransberg, was seized from its owner and converted into a massive Luftwaffe headquarters for the coming campaign, and was later utilised by Heinrich Himmler alongside Reichsmarshal Göring.

But when Hitler visited the Adlerhorst he rejected it as too luxurious and not in keeping with his image as a simple and frugal leader. He was particularly worried that after the war his loyal disciples would visit the castle as a kind of shrine and be dismayed to find out that their beloved Führer lived in such opulent surroundings while they suffered air raids and food shortages. Hitler demanded a different headquarters on a more modest scale.

The Adlerhorst would not be used until 1944, when Hitler finally moved in to direct the Ardennes Offensive, but although mothballed for the time being the site nonetheless still had to be carefully protected. Speer modified the complex for use by the Luftwaffe as their HQ for Operation ‘Sealion’, the planned invasion of Britain in 1940. After Hitler cancelled Sealion the castle was used as a recuperation centre for wounded German soldiers and as a private retreat for the corpulent Luftwaffe leader Hermann Göring.

Hitler’s RSD commander, Johann Rattenhuber, provided nineteen of his men to guard the Adlershorst complex, plus 106 military policemen – a considerable use of resources to guard an empty headquarters. This activity served as a useful distraction from Hitler’s real HQ, the considerably more basic ‘F’ or ‘Felsennest’ (Mountain Nest) that was occupied at Rodert near the town of Munstereifel, 22 miles (35km) southwest of Bonn and only 28 miles (45km) from the Belgian frontier.

At the Felsennest, Hitler took over an already existing site that consisted of some anti-aircraft positions and a few wooden huts. Engineers built catwalks between the buildings so that Hitler and his officers did not have to wade through mud, renovated the existing structures, put up security fences and gates, and built some small bunkers and air raid shelters. Hitler’s personal bunker was very small. It consisted of one room that he could use for meetings and military briefings plus a modest bedroom, bathroom, bedrooms for Keitel and adjutant Schaub, one manservant and a kitchen. ‘Jodl, Dr. Brandt, Schmundt, Below [Luftwaffe aide], Puttkamer [naval aide], and Keitel’s adjutant were in a second [bunker]. The rest had to be accommodated in the nearby village.’ But the headquarters was in keeping with Hitler’s simple nature, and importantly it reinforced his own image of the straightforward and frugal leader.

Hitler returned to the Western Front in June 1944, shortly after the D-Day landings in Normandy. His headquarters for his short visit was Wolfsschlucht II near Margival in France. He flew to Metz aboard his personal Condor aircraft on 16 June and then travelled by motorcade through the early hours of 17 June to his conference with Generalfeldmarschalls Gerd von Rundstedt and Rommel, his two Western Front commanders. The Führer’s safety when airborne was assured by the grounding of all Luftwaffe aircraft along the route and an order that no German anti-aircraft batteries would be permitted to open fire. It should be noted that by this stage of the war Hitler was taking a considerable risk still travelling by air because the Allies had managed to achieve almost complete aerial superiority over Western Europe.

The meeting with von Rundstedt and Rommel was deeply acrimonious, Hitler blaming them for their failure to force the Allies back into the sea at Normandy. They first had lunch together. Hitler watched as his special vegetarian food was tasted for him before eating any himself. Two RSD officers stood behind Hitler’s chair, their faces hard and their eyes constantly scanning the Führer’s lunch companions. Rommel told Hitler that in his opinion the German Army would collapse in France, as well as in Italy, and Hitler should end the war as soon as possible. An air raid alert forced the group underground into Hitler’s personal air raid shelter. Hitler was due to visit Army Group B front headquarters at the Chateau of La Roche-Guyon on 19 June but Hitler had suddenly departed for Germany on the night of the 17th. The reason for this was the impact of a brand new V1 flying bomb on the headquarters at Margival that night. V1 launches against London had begun on 12 June and by the 15th over 500 of these primitive cruise missiles were being launched daily. One malfunctioned and landed on Führer Headquarters, frightening Hitler enough that he decided to return to Germany and from there take his personal train back to his Eastern Front headquarters at the Wolf’s Lair.

Hitler came West once again on 11 December 1944 when his personal train arrived at Giessen Station in Hesse where a fleet of armoured Mercedes took him and his party to the Adlerhorst, the command complex that had been built several years before adjacent to Ziegenberg Castle. Although Hitler had previously refused to use the complex, complaining that it was too luxuriously appointed, by December 1944 he required a large headquarters base with excellent communications and a co-located army high command facility for the forthcoming Ardennes Offensive. His other Western Front headquarters were none of these things. The Eagle’s Eyrie was the only Führer Headquarters in the West that met these criteria and so preparations had been made for Hitler’s arrival.

The Adlerhorst consisted of seven large “cottages” set in a heavily wooded compound at Wiesental beyond Ziegenberg Castle’s main entrance. In reality, each cottage was in fact a large two-storey concrete bunker that was disguised to look like a typical “Fachwerk” or half-timbered wooden cottage.

Although constructed of concrete with walls 3 feet (0.91m) thick, the second storey included fake dormer windows with flower baskets under a sloped tiled roof. The interiors of the bunkers were kept simple, as befitting Hitler’s personal taste. They were furnished in traditional German style, with oak floors, pine wall panelling, functional brown leather furniture, wall lamps, and wall hangings depicting hunting scenes or Teutonic battles, and deer antlers.

Haus I was the Führer’s personal bunker. The decoration and furnishings were not embellished in any way. Haus II was also known as the “Casino”, a German military term for an officers’ mess. It consisted on a lounge and a café on the ground floor with bedrooms on the first floor. An entrance to the bunker below gave access to a secure situation room and communications centre outfitted with radio transmitters and Enigma coding machines. The Casino was connected to the Führerbunker by a short covered walkway so that Hitler could stay out of the elements.

(Kransberg Castle – part of the wider Adlerhorst command complex)

Haus III was occupied by a section of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (German High Command – OKW) and was the residence of the commanding general. At various times this building housed Generalfeldmarschalls Gerd von Rundstedt, Albert Kesselring and Wilhelm Keitel as well as Reichsmarschall Göring and Generaloberst Alfred Jodl.

(Copyright Battlefield-Tours.de)

Haus IV was known as the “Generals’ House” and was used by second echelon general staff, for example Hasso von Manteuffel, Ferdinand Schorner and Heinz Guderian.

Haus V was occupied by a section of Dr. Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry while Reich Ministers and very senior Nazi officials including Martin Bormann, Alfred Rosenberg and Robert Ley used Haus VI. The final cottage, Haus VII, was known as the “Wachhaus” and was the largest of the seven. It housed Hitler’s adjutants, bodyguards, personal secretaries and housekeeping staff. This building was connected to Ziegenberg Castle, as we have seen already previously converted into a secure army headquarters complex, by a 0.5-mile (0.8 km) long tunnel.

The largest building in the Adlerhorst complex was called the Kraftfahrzeughalle (Motor Pool Garage) and this was located in the village below Ziegenberg Castle. It housed the armoured Mercedes limousines used by Hitler and his henchmen as well as fire engines, busses and ambulances. There was also Fachwerk-style accommodation for the families of personnel working at the Adlerhorst.

The entire site was carefully guarded, with disguised concrete guard bunkers covering all approaches and a network of anti-aircraft batteries sited around the surrounding hills. Above the Castle, located to the north in the hills, was a disguised Wehrmacht depot that housed additional army units for the defence of the Adlerhorst.

Hitler would use the Eagle’s Eyrie between December 1944 and January 1945 during the Ardennes Offensive, his last gamble in the West. The Adlerhorst became Hitler’s last field HQ after the abandonment of the Wolf’s Lair to the advancing Soviets. The Commander-in-Chief West, Gerd von Rundstedt, moved into Kransberg Castle in October 1944 in preparation for the coming offensive but when Hitler arrived by train at the Adlerhorst on 11 December, von Rundstedt and his headquarters moved forward to near Limburg in Belgium.

On the morning of 15 December Hitler hosted a planning conference to discuss the Ardennes operation attended by von Rundstedt, Keitel, Jodl and Gunther Blumentritt and the ground commanders including von Manteuffel and Sepp Dietrich. Many of these top commanders didn’t even know of the existence of the Adlerhorst and before they had arrived they had been driven in an SS bus on a long and circuitous route through the mountains to deliberately confuse them about the headquarters location.

After Christmas 1944 Hermann Göring arrived and took up residence at Kransberg Castle. It was at a briefing inside Haus II at Wiesental that the Reichsmarschall destroyed his relationship with Hitler after he suggested, in light of the evident failure of the Ardennes offensive, that Hitler seek a truce with the Allies through neutral Swedish contacts. Hitler flew into a rage and threatened to have Göring placed before a court martial and shot.

On New Year’s Eve, 31 December 1944, Hitler made a rare radio broadcast to the German people before going to Haus I to welcome in 1945 with his close intimates including Bormann, Dr. Dietrich and two of his secretaries, Traudl Junge and Christina Wolf. Two inches of snow had fallen, giving the Castle and the surrounding pine forest a pretty and festive aspect. Hitler’s Austrian dietician, Constanze Manziarly, had laid out a buffet and there were chilled bottles of Mosel-Sekt.

Whilst Hitler was preoccupied with the Ardennes Offensive, Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, Chief of the General Staff of the Army, had visited the Adlerhorst on several occasions trying in vain to warn Hitler of the growing Soviet threat on Vistula River south of Warsaw. Intelligence summaries suggested that in the predicted main assault areas the Red Army would outnumber the Germans by 11-to-1 in men, 7-to-1 in tanks and 20-to-1 in guns. Hitler rubbished the intelligence and refused to transfer divisions east.

At 4am on 1 January 1945 Hitler attended a conference in Haus II to discuss his counter offensive in the West, Operation North Wind. Launched at midnight, the counter offensive ran out of steam by 25 January 1945 when it became clear that Germany had lost the battle and in the process used up its last remaining reserves of manpower and equipment. Also on 1 January Guderian attended another meeting with Hitler where he continued to plead for to transfer of forces east, before it was too late. Hitler only permitted the transfer of four divisions, and promptly ordered them to Hungary instead of the threatened sectors of the front.

On 9 January Guderian was back at the Adlerhorst, pestering Hitler again about the Eastern Front. At this time Hitler’s great offensive in the west was faltering, and Hitler flew into a rage, refusing to transfer divisions or even to consider permitting exposed German formations to pull back to more defensible positions. It was at this point that Guderian made his famous remark: ‘The Eastern Front is like a house of cards. If the front is broken through at one point, all the rest will collapse.’

On 15 January, with the western campaign virtually ended and with increasing signs of an imminent Soviet assault across the Vistula, Hitler left the Adlerhorst for the last time. As he was leaving aboard his train, one wit among his staff pointed out that ‘Berlin was preferential as a headquarters; it would soon be possible to travel from there both to the eastern and western front by suburban railway.’ Apparently Hitler actually laughed. He had probably been encouraged to move out of the Adlerhorst not only by the obvious failure of his offensive in the West and by the imminent Soviet onslaught from the East, but also by another close call with death.

On 6 January a RAF Lancaster bomber, possibly in trouble, jettisoned a huge Blockbuster Bomb over Ziegenburg, the town that lay at the foot of the castle. The late-war Blockbuster, known to the RAF as the “Cookie”, was the largest conventional bomb used by any of the Allied air forces and was packed with 12,000-lbs (5.4 tonnes) of Amatol high explosive and they were designed to level entire city blocks with one strike. One bomber crew recorded that when they dropped one into the centre of Koblenz the tremendous explosion damaged their Lancaster flying at 6,000 feet (1,829m). The explosion at Ziegenburg, which was not densely populated or built-up, killed four civilians, wrecked the local church and caused extensive damage to surrounding houses. If the bomb had landed on the Führerbunker Hitler could have conceivably been killed. Hitler returned to Berlin on 16 January 1945 aboard his private train, the Führersonderzug.

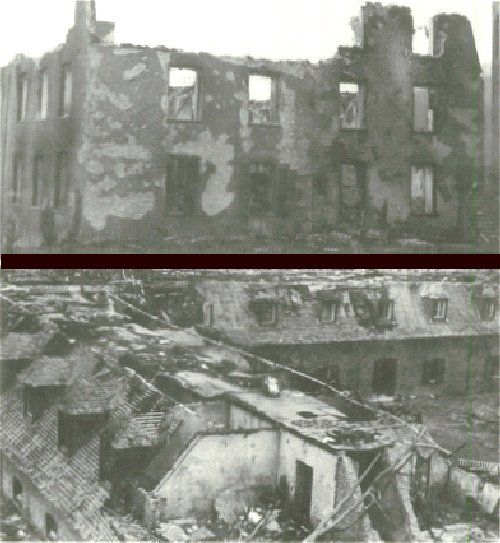

The Western Allies thought that Hitler was still at the Adlerhorst, his headquarters at Ziegenberg Castle, and they determined to try and kill him. Although Hitler had already been gone for two months, on 19 March 1945 a squadron of P-51 Mustangs launched a precision attack on the Castle and its environs, dropping high explosive and incendiary bombs that killed ten civilians and did huge damage to both the Castle and surrounding buildings. But the Allies completely missed the real headquarters complex – the disguised bunkers at Wiesental. Ziegenberg Castle was burned out by napalm and turned into a ruin.

Ziegenberg Castle following the US air raid. (castlesingermany2.homestead.com/Ziegenberg)

The bunker complex at Wiesental was still functioning as a headquarters at the time of the raid and afterwards. On 11 March the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief West, Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, had moved in with his large staff. He immediately ordered that all sensitive documentation and cipher machines be removed from Ziegenberg Castle, after which he moved with his staff into Haus III, the purpose-built OKW command bunker at the Adlerhorst. Kesselring and his staff escaped harm during the 45-minute American air raid.

By 28 March, with US forces only 12 miles (19 km) from the Adlerhorst, Kesselring ordered the evacuation by means of all the remaining motor transport of civilian employees and the families of soldiers who were serving at the headquarters. He then ordered that the Adlerhorst complex should be blown up. This was only partially successful. When the US Army arrived they discovered that the Führerbunker and several other structures had been reduced to burned-out shells, but two buildings were captured intact. The first was Haus V or ‘Pressehaus’, used by Goebbel’s Propaganda Ministry. The second was the largest building on the site, Haus VII, the ‘Wachhaus’ with its long concrete tunnel that connected directly with the Castle.

Today, both Ziegenberg and Kransberg Castles remain in private hands, and are not easily accessed by the public. The bunker complex at Wiesental is also mostly intact.

See also Tiger Hunting in the Ardennes