The ‘Wolf’s Lair’ conjures up images of danger, of hidden menace, of evil power. It was named by Hitler himself, playing on his own preoccupations with the wolf as metaphor for himself. Hidden beneath a canopy of fir trees, in the summer the complex of huge above ground concrete bunkers and net covered walkways was alive with the buzzing of mosquitos that thrived in the humid and unheathy local conditions. During the winter the forest was silent and heavily snow laden, the surrounding lakes frozen solid in the bitter cold.

The Wolf’s Lair was very well-named, hidden as it was deep in the gloomy East Prussian forest 5 miles (8km) east of Rastenburg (now Ketrzyn, Poland) and it was here that Hitler would spent most of the war, over 800 days in total, directing the monumental fight against the Soviet Union.

The site chosen by Dr. Fritz Todt was codenamed initially Anlage Nord (Installation North); it eventually became known as the Wolfsschanze (Wolf’s Lair). A one-track railway and a road ran through the Wolf’s Lair connecting the town of Rastenburg with Angerburg and Lotzen where other headquarters staffs were located.

The Wolf’s Lair complex, initially a collection of concrete bunkers and wooden huts, was in the middle of a dense fir forest and the complex covered 2.5 square miles (6.475 square km) and was divided into three security zones, or Sperrkreise. Where trees were felled to create space for buildings, artificial trees and camouflage netting was installed to maintain a continuous tree canopy. A company from Stuttgart was brought in to disguise the buildings, planting bushes, grass and artificial trees on the flat roofs. Roads were also partly disguised by camouflage netting and fake trees. The Germans carefully photographed the completed site from the air to test the camouflage, but the Soviets were soon aware of the existence of the headquarters and of its purpose.

Hitler’s train was kept under more nets and trees at Bahnhof Gorlitz, the Wolf’s Lair’s private station. Hitler first arrived at the Wolf’s Lair by train on 24 June 1941 and would stay, with some large breaks when he was in Berlin, Munich, and Berchtesgaden or at Werwolf, another Eastern Front headquarters, until 20 November 1944.

Visitors could arrive at the Wolf’s Lair using four methods. The first method was by train, arriving at Gorlitz Station. Every night two identical courier trains left from Silesian Station in Berlin and the town of Angerburg in East Prussia, arriving at the opposite destination the next morning. The second method was by plane, arriving at Rastenburg Airfield southwest of the Wolf’s Lair. Thirdly, the headquarters complex could be approached by road from the west, south or east. Fourthly, a rail trolley, a kind of tram, commuted between the Wolf’s Lair and the OKH “Mauerwald” command complex near Angerburg with stops at Gorlitz Station and at the eastern entrance gate near the Luftwaffe liaison offices.

In order to enter Sperrkreis I, the complex’s inner sanctum where Hitler lived and worked, one would have to pass through at least four security checkpoints.

Sperrkreis III was the outer security area consisting of fences, gates, slit trenches and guardhouses. The perimeter was extensively mined. After the war the Soviets removed 54,000 landmines from the complex. Close by to the northeast of Sperrkreis III was a Wehrmacht operations staff facility and army headquarters. Additional troops were stationed 45 miles (72km) away in case of an emergency. This unit, a kampfgruppe (battlegroup), was under the command of highly decorated combat officer Generalmajor Walter Denkert. It was later envisaged that Kampfgruppe Denkert would be used to garrison proposed Festung (Fortress) Lotzen. Denkert’s troops had responsibility for guarding the area outside of Sperrkreis III.

The FBB was responsible for guarding and defending Sperrkreis III. The unit was expanded in April 1943 by the creation of a second unit, the Führergrenadierbataillon (FGB) from selected Grossdeutschland personnel. The FBB and FGB had tanks, anti-tank and anti-aircraft units and mechanized infantry with which to defend the Wolf’s Lair.

Within Sperrkreis III, like a Russian doll, sat Sperrkreis II. It was a self-contained fenced area lying north and south of the Angerburg road. It contained concrete and brick one-storey houses of the Wehrmachtfuhrungsstab (Armed Forces Leadership Staff) and the headquarters of the Wolf’s Lair Commandant and his staff. There were two messes, heating plants and a communications centre. East of the buildings, and south of the road, were more concrete and brick houses containing the Kriegsmarine (Navy) and Luftwaffe liaison offices, a two-storey building for drivers with a large garage on the ground floor to store and maintain Mercedes limousines, two tall air raid bunkers, FBB barracks and the barracks for the Führer-Flak-Abteilung (Führer Anti-Aircraft Detachment). Sperrkreis II also contained housing for some of the senior Nazi leaders including Hitler’s Armaments Minister Albert Speer and Reich Labour Front leader Fritz Todt (until his death in a plane crash in February 1942).

Sitting like the yolk at the heart of the Wolf’s Lair egg was Sperrkreis I – the holiest of holies. Within Sperrkreis I was the Führerbunker as well as a collection of ten concrete bunkers or concrete and brick houses for the inner circle and their staffs. These consisted of bunkers for Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel, Head of the Armed Force (OKW), Press Chief Dr. Otto Dietrich, Martin Bormann, a second communications centre, Generaloberst Jodl, Chief of the OKW Operations Staff, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, the Army Personnel Office, and the Adjutants Office. There was a house for the shorthand writers who transcribed all of Hitler’s conversations and orders. Each bunker was above ground, the marshy soil precluding very many subterranean constructions, and each was built of steel reinforced concrete with 6ft 5in (2m) thick roofs to protect from aerial bombs. Hitler became increasingly and somewhat morbidly fascinated by the idea of an Allied bombing raid on the Wolf’s Lair and once remarked to his secretary Traudl Junge: ‘They know exactly where we are, and sometime they’re going to destroy everything here with carefully aimed bombs. I expect them to attack any day.’

To ensure his survival Hitler had Sperrkreis I extensively rebuilt in 1944, Albert Speer spending 36 million Reichsmarks reinforcing the bunkers. The Fuhrerbunker was turned into a veritable fortress containing a large maze of passages, rooms and halls. The roof was increased to a thickness of 23 feet (7m), with a layer of gravel within designed to provide a cushioning effect and prevent the cracking of the inner bunker shell if struck by large aerial bombs.

Within Sperrkreise I were also several RSD command posts, Hitler’s personal air raid shelter, the Secretariat under Philipp Bouhler, Johann Rattenhuber’s RSD security headquarters, a post office, radio and telex buildings, vehicle garages, a siding for Hitler’s private train, a cinema and generator buildings.

There were quarters for Hitler’s personal physician, the fat and unpopular Dr. Theodor Morell, Hitler’s chief Luftwaffe adjutant General der Flieger Karl Bodenschatz, Walter Hewel of the Foreign Ministry, Vizeadmiral Hans Voss of the Kriegsmarine, and after 1943 SS-Brigadeführer Hermann Fegelein, representing Himmler’s SS. Martin Bormann always close by his Führer, having in addition to his personal bunker a nearby staff accommodation house and an air raid shelter. Hitler’s bunker was located at the northern end with all of its windows facing north to avoid direct sunlight. Hitler, Keitel and Jodl’s bunkers had built-in conference rooms.

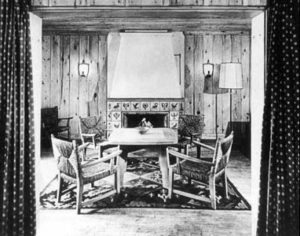

For relaxation Sperrkreis I also had an officers’ mess, a mess room, teahouse, sauna, heating plant and a communal air raid shelter. The interiors were Spartan, as Hitler intended all of his field headquarters to reflect his own personal tastes and his concern to distance himself from his ‘official’ home in the grand and ostentatious Reich Chancellery in Berlin. Hitler always wanted to appear as a humble and frugal man in front of his people, though ironically his security needs ended up absorbing huge amounts of money and manpower that could have been more profitably used helping the war effort. For example, in 1944 alone, Bormann had 28,000 forced labourers working on improving Hitler’s various headquarters when every able-bodied worker was needed in the armaments industry.

To guard further against the possibility of air attack there was a radar system that was able to locate incoming enemy aircraft up to 60 miles (96km) away, giving several minutes warning of an air raid, though the Wolf’s Lair was never seriously targeted by either the Red Air Force or the British and Americans. The Führer-Luft-Nachrichten-Abteilung (Führer Air Intelligence Detachment) had many observation posts to back up the radar system. If a plane was detected inside the security zone an alert list of key persons were immediately evacuated to shelters by the RSD or SS-Begleit-Kommando. Soviet planes did drop a few bombs on Sperrkreis III on one occasion, but other than this one nuisance raid the enemy left the Wolf’s Lair in peace.

Certain senior Nazis were prevented from having offices inside the Wolf’s Lair by Bormann, most notably Heinrich Himmler and Joachim von Ribbentrop. The OKH was also located elsewhere, only having adjutants at the Wolf’s Lair and regular visits by army commanders.

The OKH Eastern Front HQ was codenamed ‘Mauerwald’ and consisted of two sections that were separated by the Rosengarten–Angerburg road. ‘Fritz’ contained the General Staff offices and bunkers while ‘Quelle’ housed the supply section and general administration offices. The HQ was decentralized for security reasons, some personnel living in barracks in Angerburg, Lotzen and other local towns. In total, around 1,500 officers and men worked at Mauerwald. The generals and other senior officers were guarded by sixty secret military police and the entire site patrolled by two companies of older Wehrmacht soldiers who were unfit for frontline duty.

Hitler was always concerned about enemy parachute attack on his headquarters or those of the army high command and other important complexes close to the Wolf’s Lair. Hitler had sited his Eastern Front headquarters in dense forest in an attempt to preclude the Soviets from attempting this form of assault, because paratroop units that jump into forests generally suffered huge casualties from injuries sustained when striking the canopy, or prove easy targets for defending forces when strung up in the trees. The area around the Wolf’s Lair contained few open spaces big enough for the kind of enemy force that would be required to overwhelm the FBB units defending the Führer. But in winter this was not the case. The large lakes, including the nearby Moy-see and Zeiser-see, that dotted the marshy East Prussian landscape froze solid, providing perfect drop zones for paratroopers or glider-borne commandos. There was also a small landing strip for Fieseler Fi-156 Storch spotter planes south of the facility. Also located nearby, and separate from Hans Baur’s Führer Squadron (F.d.F) was the Führer Kurier Staffel (Führer Courier Squadron) under the command of Luftwaffe Hauptmann Talk. This unit consisted of between six and twelve fighters that could be used to quickly move around documents or dispatches and to ferry messages.

The threat from paratroopers was limited to some extent when the FBB dug in 20mm anti-aircraft cannons around the lakes to be used in the ground role, and to punch holes in the ice in the event of a sudden enemy landing. In the town of Goldap, 43.5 miles (70km) northeast of the Wolf’s Lair was a German paratroop battalion that was kept in a high state of readiness. If enemy forces or partisans penetrated the Wolf’s Lair’s security zone, these German paratroopers had orders to fly directly to Hitler’s aide and jump into action over Sperrkreise I, II, and III, Hitler apparently having no qualms about the casualties that these elite troops would suffer jumping into a forest canopy or landing on minefields.

Hitler and his staff would seal themselves inside their gas and bomb proof bunkers and await relief. Other nearby troops included SS Anti-Tank Training and Replacement Battalion 1 in Rastenburg.

As at the Berghof in Bavaria, so life for Hitler at the Wolf’s Lair was fairly relaxed and very routine. Hitler was remarkably indolent for a man attempting to hold his crumbling empire together, and usually rose late in the morning. After rising, washing and being shaved by his valet and taking breakfast Hitler would walk his Alsatian dog Blondi within Sperrkreis I between 9 and 10am. He did this alone with only his own thoughts for company. At his military headquarters Hitler always wore a form of uniform unique to him. Before the war Hitler was often seen dressed in a brown tunic with red and gold Nazi Party armband and black trousers, but he never wore this uniform once the war began. Instead, he would wear a high double-breasted military-style field grey tunic with a golden German eagle the left upper arm, white shirt, black tie, black trousers and leather shoes and a grey and brown peaked cap with gold embroidered eagle and national cockade.

When he was walking outside he usually also wore kid leather gloves. On the left side of his tunic were three badges – his Iron Cross First Class and Wound Badge in Black from the First World War and his Nazi Gold Party Badge. He was entitled to wear four other First World War decorations (Iron Cross Second Class, Bavarian Cross of Military Merit, Third Class with Swords, Bavarian Medal of Military Service, Third Class, Honour Cross of the World War 1914-18 with Swords) but never did. He was very proud of his Iron Cross and he wore it, along with his Wound Badge, to demonstrate his wartime courage and service to the ‘Fatherland’.

At 10.30am the mail was brought in to him. At noon he would walk across to Keitel and Jodl’s shared conference room for the first of the two daily situation briefings delivered by the military high command. This event, known as the ‘situation discussion’ was the most important event of the day. Depending on the news, this meeting might last for up to two hours. Lunch was served in the dining room promptly at 2pm. Hitler usually sat in the same place, between press secretary Dr. Otto Dietrich and Generaloberst Jodl. Opposite usually sat Keitel, Bormann and General der Flieger Bodenschatz. This arrangement was changed after a heated argument between Hitler and Jodl one lunchtime in early September 1942. Afterwards, Hitler ate along or with two of his secretaries until he became bored and a fresh list of lunch companions was drawn up.

Following his vegetarian meal Hitler would deal with non-military matters, particularly any meetings or receptions. He frequently had important international guests to talks at the Wolf’s Lair. Some of the notable visitors included Tsar Boris III of Bulgaria, Admiral Miklos Horthy of Hungary, Admiral Pierre Laval, Prime Minister of Vichy France, Finnish statesman Field Marshal Carl Mannerheim, Mussolini and the Japanese Ambassador, General Hiroshi Oshima.

At 5pm Hitler would call the two female secretaries that he took with him to the Wolf’s Lair in to take coffee with him, as well some of his military aides. ‘A special world of praise was bestowed on the one who could eat the most cakes.’

At 6pm sharp there occurred the day’s second military briefing, the briefing delivered by Jodl. Dinner was served at 7.30pm, often dragging on for two hours as Hitler subjected his guests to one of his infamous monologues.

Afterwards, Hitler and his inner circle, and any high-ranking guests that were visiting him, usually repaired to the cinema to watch films and newsreels. Then Hitler would retire to his personal quarters, usually with Bormann and his two female secretaries, and talk or listen to music until the early hours. ‘Sometimes, it was daylight by the time the nocturnal discussions came to an end.’ As the war started to go badly for Hitler the atmosphere around changed. Towards the end Jodl was to describe the Wolf’s Lair as halfway ‘between a monastery and a concentration camp.’

Hitler’s two secretaries at the Wolf’s Lair, Christa Schroeder and Gerda Daranowski (later Christian) were given very simple living quarters. ‘The sleeping section of their bunker was no larger than a compartment in a railway carriage. It had a toilet, a mirror, and a radio, but not much else. There were shower rooms.’ They were also under-employed in the almost exclusively male-dominated world of the Wolf’s Lair, drawing criticism from many of the adjutants. But it appeared that Hitler liked to have females around for company. ‘They had as good as nothing to do. Sleeping, eating, drinking, and chatting filled up most of their day.’ The job of being Hitler’s secretary was not, apparently, a particularly happy one. ‘We are permanently cut off from the world wherever we are,’ complained Schroeder in a letter to a friend in August 1941, ‘in Berlin, on the Mountain [Obersalzberg], or on travels. It’s always the same limited group of people, always the same routine inside the fence.’

Security and guard duties along the fences of Sperrkreise I and II were primarily the responsibility of the FBB. Hauptmann Gaum, an FBB officer, made this point emphatically to his British interrogators in late 1944. Three guard companies were on active duty at any given time, day or night. Inside Sperrkreiss I the primary bodyguards were RSD and SS-Begleit-Kommando. RSD Bureau I worked in cooperation with the SS. An SS-Begleit-Kommando officer was responsible for guard changes and patrols by both services as well as guards at the cinema, the issue of passwords, and supervising guards details in their quarters before they came on duty. Permanent guards were mounted as follows:

- SS-Begleit-Kommando guard in front of the Führerbunker day and night.

- RSD officer on constant patrol around the Führerbunker day and night.

- RSD officer in front of the shorthand writers’ building day and night.

- RSD officer patrolling throughout Sperrkreis I between 10am and 6pm.

Hitler’s permanent adjutants were empowered to use the RSD guards for small errands as required. Anyone leaving one bunker to visit another bunker had to have permission. Officers were not permitted to freely wander around Sperrkreiss I. Identity papers could be demanded at any time, and the RSD would check them thoroughly and the person would then be escorted to his destination or to an exit gate into Sperrkreis II. The RSD guards were not supposed to stand around chatting or to walk in pairs. When Hitler was walking his dog or strolling the grounds in conversation with a member of the inner circle or a guest, the RSD officer on roving patrol was supposed to keep other people out of earshot of Hitler, and also make sure that he stayed well back. RSD guards were also not permitted to enter the Führerbunker unless they were escorting in a workman or a maintenance engineer. Any messages or packages for the Führerbunker were handed to one of Hitler’s adjutants at the main door.

Although it appeared that the guards always followed strict protocol regarding passes, Hauptmann Gaum noted that this was not always rigorously applied for the top Nazis. ‘If a person such as Himmler or Göring were seen approaching slowly in a car, he might possibly be let by without being checked by the sentry, but in that case the sentry would ring the Ic of the Camp Commandant, who was the official responsible for issuing passes to persons before entering the FHQ.’

Hitler was frightened of the noxious vapours that were given off from his ferro-concrete bunker walls at the Wolf’s Lair, so the RSD maintained oxygen tanks outside of the bunkers ready to pump in fresh air. These tanks were regularly tested. The bunkers were also fitted with anti-gas chambers to prevent the enemy or any would be assassins from pumping poison gas into the bunkers through the air ventilation system.

On 20 September 1943 Hitler, returning to Wolf’s Lair from his other Eastern Front HQ codenamed Werwolf, decided to further tighten up his security arrangements. Rudolf Schmundt and NSKK-Gruppenführer Albert Bormann, Martin Bormann’s brother and one of Hitler’s closest aides, issued a new directive to further intensify security and secrecy within Sperrkreis I. A new inner sanctum was created called Sperrkreis A. It included Keitel’s bunkers and annexes, Hitler’s personal adjutants building, Mess No. 1, the teahouse, the Führerbunker, Martin Bormann’s bunker, the Wehrmacht Adjutants’ Office and the Army Personnel Office. Only those serving with Hitler directly or those who had offices within Sperrkreiss A, or those who lived there, were allowed in regularly. New passes were issued by the RSD.

Additional passes could be issued by HQ Commandant only on the authority of Schmundt or his deputy in consultation with Hitler’s aide SS-Obergruppenführer Schaub or his deputy. The guard could issue day passes only after a personal or military adjutant of the Führer had given his permission. No one was allowed inside Sperrkreis A without a valid pass. Anyone found without the proper documentation, regardless of rank, would be immediately arrested by the RSD.

Three gates gave access to Sperrkreiss A – one by Keitel’s bunker, one next to the Adjutants’ House and one by Bormann’s building. One RSD officer and one FBB NCO manned each gate. The FBB was responsible for checking passes and the RSD man assisted. In addition, one RSD officer was on constant patrol within Sperrkreiss A.

A special list of thirty-eight persons was created by the RSD. These men and women were permitted to dine with the Fuhrer at lunchtime in Dining Room No. 1, and Hitler would select several each day from the list who were then issued with passes for Sperrkreiss A. In addition, a further forty-three aides, valets, typists and shorthand writers were on another list permitting them to dine in Dining Room No. 2 inside Sperrkreiss I.

These new security precautions made any attempt to kill the Führer considerably more difficult. An assassin would firstly have to have a valid reason to enter the Wolf’s Lair complex, and would have to pass through four identity checks before gaining direct access to Hitler. Very few people were given passes for Sperrkreiss I, let alone the new inner sanctum of Sperrkreiss A. But those determined to kill Hitler were resourceful and often well-connected individuals who were prepared to use Hitler’s security precautions to their own advantage. During 1943-44 trusted men who were close to Hitler tried to kill him on several occasions. It would only take the right circumstances for one of these brave men to succeed and change Germany and the world’s destiny in an instant. The countdown to Operation Valkyrie had begun…

Further reading: