Article List

1. Terror on the Yangtze: The Destruction of the USS Panay

2. The Italian Battalion in China and the Fate of Italy’s Far Eastern Forces: 1925-1945

Terror on the Yangtze: The Destruction of the USS Panay

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 has gone down in history as the formal entry of the United States into the Second World War and the expansion of the war from a European event into a global conflict. It was not the first occasion, however, that American and Japanese military forces had clashed. The first shots fired between the two nations occurred on the Yangtze River in China in 1937, when America found herself caught in the crossfire as Japanese troops were in the process of overrunning eastern China. In a deliberate and calculated move, Japanese troops and aircraft successfully sank the American river gunboat USS Panay as Japanese forces converged on the temporary Chinese capital of Nanjing. The river borne battle also involved gunboats of Britain’s Royal Navy, as European and American diplomatic and civilian personnel evacuated the city and headed deeper into China.

American involvement in China dated from the mid-19th century, when alongside other Western powers, America was keen to open the Chinese market for trade purposes. The resulting ‘unequal treaties’, which were signed between China and the Western powers following British success in the 1842 Opium War, meant foreigners were permitted to reside and trade at specific treaty ports around China. The Western powers also opened diplomatic missions across China, and coupled with the importance of trade, determined to protect their interests by stationing military and naval forces throughout China, ostensibly to protect river borne trade from pirates. The Yangtze River Patrol of the US Navy’s Asiatic Fleet, in common with the other powers, utilized shallow-draught gunboats to patrol the river systems.

From the 1860s until the turn of the 20th century tours of duty were largely uneventful, but the situation then began to deteriorate as the Chinese Imperial Court under the Empress Dowager Cixi (pronounced Sir Shi) began agitating for a removal of western influence in the country. This unrest culminated in the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, when European, American and Japanese forces defended their besieged legations in Beijing and Tianjin until relieved by an international force. The Americans upgraded their river gunboats, acquiring Spanish-built examples as spoils of war in the Philippines. Later, US-built vessels were sent to China, culminating in the last modernization of the fleet between 1926 and 1927. Three sizes of vessels were constructed in Shanghai: the USS Luzon and USS Mindanao were the largest, followed by the mid-sized USS Oahu and USS Panay, and the small USS Guam and USS Tutuila. All six vessels were, however, capable of operating as far inland as the city of Chongqing, enabling America to protect its river borne trade effectively.

The USS Panay was constructed in 1928, displaced 474 tons, and measured 191 feet in length. She was constructed of steel, and mounted two 3in guns and eight .30 cal. machine guns. In 1937 she was skippered by Lieutenant-Commander James J. Hughes USN, with a complement of fifty-eight all ranks. The Japanese were rapidly advancing inland after their conquest of Shanghai, and Hughes task was to standby on the river outside Nanjing and await orders.

The Japanese invasion of China had begun on 7 July 1937, when a Japanese rifle company, supposedly searching for a missing comrade outside of Beijing, had demanded entry to the walled town of Wanping. The Chinese commander denied permission, and fighting broke out. Such skirmishes had been occurring with increasing regularity in China since 1931, as Japan attempted to provoke Nationalist China into a war in which Japan could use her superior military machine to rapidly overrun eastern China. This would mean that Japan could secure for herself the valuable raw materials required to maintain her growing economy and military, and allow Japan to carve out for herself a continental empire to rival the Western colonial possessions at that time dominating Asia. Although the Chinese leader, Chiang Kai-shek, ruling from Nanjing, had previously overlooked clashes between his troops and the Japanese, in 1937 he attempted to stand up to them, with disastrous results. Japanese forces captured Beijing, and from their concession in Shanghai fought a bloody battle to invest the rest of the city. The United States maintained a trade concession in Shanghai, as well as a military presence, and although the Japanese would not take over the European and American concessions in the International Settlement until December 1941, Americans were nonetheless caught up in the battle for the city. The cruiser USS Augusta, moored on the Huangpu River in Shanghai, was hit by a stray Japanese 37mm shell during the fighting, which killed one sailor and seriously wounded eighteen others.

Japanese forces fanned out from the coast, fighting their way inland towards Chiang’s Nationalist capital at Nanjing, where the Western nations had established their embassies, as well as missions, trade concessions and schools. Chinese units managed to put up a good fight outside the city, but were on the verge of being overrun when the order came on 21 November to evacuate the diplomatic staff and other civilians from Nanjing by river. The American ambassador, Joseph Grew, left the next day with his staff aboard the USS Luzon, but the rest of the American civilians stayed in Nanjing for a further week until it became clear that the city was definitely going to fall to the Japanese. Chiang’s army, consisting of six corps, doggedly resisted the Japanese advance, but the Japanese eventually broke into the city’s suburbs. Grew duly notified the advancing Japanese on 1 December that neutral American civilians were evacuating Nanjing aboard the USS Panay, and she departed upriver on 11 December escorting three American-owned oil barges. Following in the little flotillas wake were several Royal Navy gunboats and smaller craft loaded with British nationals escaping the Japanese onslaught, making for a total of ten neutral vessels steaming upriver. Unfortunately, Japanese artillery units along the bank of the river engaged in the reduction of the Chinese defence of Nanjing swung into action against the ships. The Japanese artillery commander, Colonel Hashimoto, was an ardent militarist, and saw an opportunity for goading the United States into declaring war on Japan, which would have allowed the army to remove the last vestiges of civilian control from the government in Tokyo. Hashimoto is believed to have reported to other Japanese units that the ships were Chinese, and full of Chinese troops escaping the envelopment of Nanjing, even though he must have been made aware of Ambassador Grew’s telegram to Japanese forces declaring them to be neutral by his superiors. Hashimoto definitely ordered his artillery batteries to open fire on the fleeing ships, but fortunately the shellfire was sporadic and inaccurate, which allowed Hughes to lead the Panay and the three American oil barges out of range.

The next day, 12 December, the little flotilla was anchored upstream from Nanjing at Hoshien. The ships’ crews were busy painting American flags on the sides of the vessels and on the sun awnings and all were flying American flags. It was a clear and sunny winters day in central China, and the officers and men aboard the Panay believing themselves clear of the fighting around Nanjing were taking Sunday lunch when all hell broke loose. Three Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service aircraft suddenly appeared overhead, catching the Americans completely by surprise. The Panay’s main and secondary armaments were still covered, and the ship was anchored in the channel when the attack began. Eighteen bombs whistled down from the aircraft just after 1.30pm, some of which struck the gunboat while crewmen rushed about attempting to man the machine guns, their only weapon of use against aerial attack. The pilothouse, sickbay and the fire room were wrecked, and Commander Hughes one of the men wounded in the initial attack. The three Japanese Navy bombers retired from the scene, but shortly afterwards twelve Japanese Navy dive-bombers, escorted by nine fighters, arrived to finish off the stricken American gunboat. By now, crewmen were beginning to fight back with their woefully inadequate anti-aircraft defence, the little ship being pounded and strafed for twenty minutes until, at 2.06 pm, the chief engineer reported a total loss of power throughout the vessel, and no propulsion available to attempt to evade the aircraft. Hughes ordered a radio operator to inform US Asiatic Fleet that the Panay was under Japanese attack and sinking, before he gave the order to abandon ship. The survivors took to the boats and rowed for the riverbank as Japanese fighters flew strafing runs over them. The boats were landed among reed beds that lined the shore, where the Americans attempted to take shelter, but even here prowling Japanese fighters strafed incessantly. The oil barges accompanying the Panay were also badly hit, two eventually sinking under the aerial onslaught from the Japanese.

Hughes, though wounded, remained in command ashore, getting word to other naval assets in the region through the local Chinese that they needed to be rescued. Hughes had lost two seamen and a civilian passenger killed in the attack, and eleven, including Hughes, were wounded.

On 13 December the remaining pockets of Chinese resistance in Nanjing surrendered to the Japanese, Chiang having lost five of his six army corps, and left 100,000 Chinese soldiers trapped in the capital. Chiang managed to disengage one corps and begin a retreat deeper into China. Over the next few weeks the Japanese sacked the city in what has become known as the Rape of Nanking, murdering nearly 370,000 Chinese soldiers and civilians, and raping upwards of 80,000 Chinese women. Chiang and his much-depleted army fell back on the city of Hankow, pursued by the Japanese. On 14 December the survivors of the USS Panay were rescued by the USS Oahu and the British gunboat HMS Ladybird and taken upriver to safety. Surprisingly, in view of the overtly hostile actions of the Japanese against a neutral American ship, the United States chose not to declare war, and instead viewed the incident as a case of mistaken identity on the part of the Japanese. Cooler heads also prevailed in Tokyo, with the government happily paying an indemnity for the destruction of the Panay in return for continued trade with the United States. Subsequently, it has become known that although Colonel Hashimoto definitely knew the identity of the American warship when he ordered his artillery batteries to open fire, the Navy planes which attacked and sank the Panay were following army intelligence sources which genuinely believed the ships to be Chinese. How these aircraft failed to recognize the blatant American insignia clearly painted on the ships will perhaps never be explained – except that perhaps there was a general consensus among Japanese intelligence that such an attack would have good results for Japan in the long term.

After the Japanese had managed to overrun a good portion of China, the river borne Yangtze trade was now under their control, which left little for the remaining American gunboats to do. They were withdrawn, or were in the process of withdrawing, when the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred in 1941, and the Japanese moved to immediately to seize the remaining trade concessions in China. The USS Guam had been renamed the Wake, and alongside the USS Tutuila they represented the last of the US Navy Yangtze River Patrol. The Wake was moored in Shanghai when the Japanese moved to occupy the British and American sectors of the International Settlement on the morning of 8 December 1941. She was moored close to the British gunboat HMS Peterel, both ships operating under strength. A party of Japanese troops boarded the Wake and she surrendered without a shot being fired, the only US Navy warship to be surrendered to the Japanese during the Second World War. HMS Peterel decided to make a futile stand, and was pounded to pieces by a Japanese destroyer and shore artillery, the surviving crew being rounded up at gunpoint while they were taking refuge aboard a neutral Panamanian registered Norwegian cargo ship across the harbour. USS Tutuila was at Chongqing, the new Nationalist Chinese capital following the fall of Nanjing, and with no way to get the gunboat out she was turned over to the Chinese Navy. It was discovered in 1945 that the Chinese Navy was operating five former British, American and French craft deep in China, their original crews having got out overland to safety. In 1941, the remaining American gunboats that had been evacuated all the way to Manila were all subsequently lost due to enemy action or scuttled as the Japanese overran the Philippines, and their unfortunate crews made prisoners-of-war. One vessel, the USS Luzon, was salvaged by the Japanese, and saw service in the Philippines until the end of the war.

Following the defeat of Japan in August 1945, the United States did not return to China, unlike the British who returned to claim their colony of Hong Kong, and their trading rights in Shanghai – and even to attempt to reintroduce patrols of the Yangtze until the Communist victory of Chiang’s Nationalists in 1949.

The Italian Battalion in China and the Fate of Italy’s Far Eastern Forces: 1925-1945

The Italian contribution to the Second World War has been generally discussed with reference to Mussolini’s support for the Nazi war effort, and his own bungled attempts to recreate the Roman Empire in North Africa. What has often been overlooked is the involvement of Italian military forces in the war in the Far East. Of particular interest were the Italian efforts to defend their possessions in the Far East following the overthrow of Mussolini in September 1943, which led to Italy changing sides, and which placed its Far Eastern forces in a confrontation with Japanese forces which led to open hostilities.

The Italians have been consistently portrayed, with the exception of their alpine forces, as being only too willing to lay down their arms when confronted by determined forces, such as the British in the campaigns of the Western Desert, which has led to an historical evaluation of the quality of the Italian armed forces of the Second World War as being consistently less professional, and less well-led, when compared with their battlefield adversaries. It will be surprising to learn that in 1943 the garrison units of the Italian Battalion in China displayed extreme courage and tenacity in hopeless resistance against one of the most formidable foes any nation faced during the Second World War – the Imperial Japanese Army. Heavily outnumbered and outgunned, Italian forces at Beijing fought desperately following the Italian surrender in September 1943, with no hope of any relief. A similar engagement was narrowly avoided in Tientsin (now Tienjin), south of Beijing.

Following the conclusion of the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900, Italy, along with many other European nations, was granted international concessions in China, and in order to secure their trade rights in Asia, and to protect their interests in common with the other nations Italy stationed troops close to their cantonments, and maintained a small naval presence in the Far East. The Italians had been granted concessions in Beijing, Shanghai and Tientsin, and these areas had been governed under the direct sovereignty of Rome since 1901. From that time onwards, the Italian government had decided to encourage the growth of missions, communities and commercial interests within the three concessions. Naturally, a special military force was required to protect Italian interests in China. However, until 1925, military protection was provided at Tientsin, for example, by only a company of Bersaglieri that numbered around two hundred officers and men, supported by a special battalion composed of former Austro-Hungarian prisoners-of-war. Imperial Russian forces had captured these men in Galicia during the First World War, then released and shipped them to the Far East to reinforce the Italian military establishment in China during the remainder of the war. During the First World War, the Italian concession in Tientsin had a Chinese population of approximately 10,000, with a further 350 to 400 Italian civilians living among them. Fifty Chinese were raised into a militia to support Italian forces.

In 1925 Rome had decided that their forces in China required reorganization into a professional intervention force. The men for the new force were drawn from an elite Italian Army unit, the San Marco Regiment and from elements of the Royal Italian Navy. The new force numbered around 350 men, and was named the Italian Battalion in China, organized as a headquarters and the San Marco, Libia and San Giorgio rifle companies.

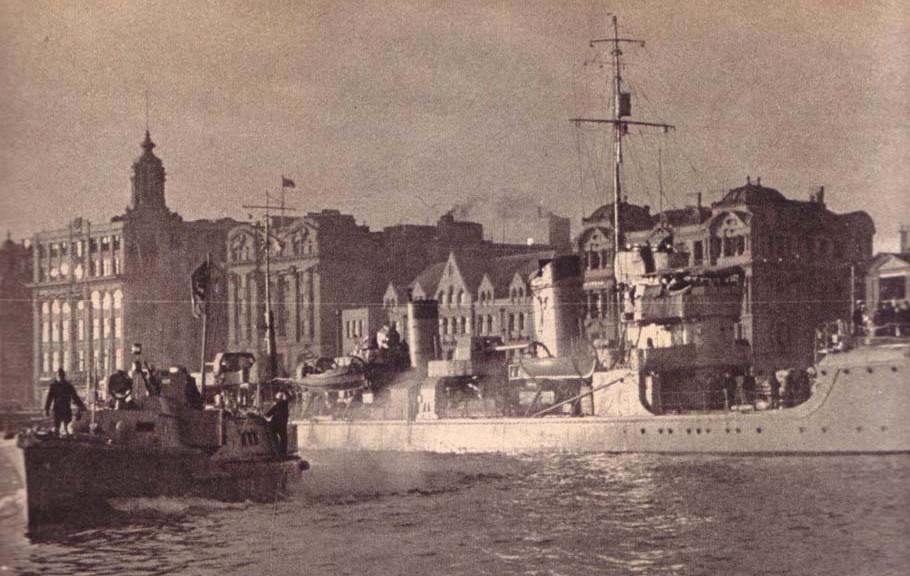

Although the Japanese had begun their conquest of China in 1931, the international concessions were not attacked or occupied by Japanese forces. On November 6 1937 Italy signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, and Mussolini opened diplomatic exchanges with Japan. Prior to the Pact, Italy had maintained a close relationship with nationalist China, led by General Chiang Kai-Shek. The Italian move towards a closer relationship with Japan caused China to break off all relations with Rome, and the Chinese effectively isolated the Italian concessions. Military and National Fascist Party representatives within the concessions became alarmed, and demanded that the Italian government provide adequate forces for the protection of Italian interests in China, including the dispatch of naval assets. Skirmishing between Japanese and Chinese forces began in July 1937, and at this time the crew of the Italian gunboat Lepanto was formed into a composite defence detachment. As the Japanese invasion and conquest of China began in earnest, the Italian High Command dispatched several hundred soldiers to defend the concessions. By September 1937, a force of 1,200 soldiers and sailors protected the estimated 600 Italian nationals’ resident within the three concessions in Beijing, Tientsin and Shanghai. In addition, the light cruiser Raimondo Montecuccoli arrived in Shanghai on September 15, just as the Japanese began their first air raids on the city.

At Tientsin and Shanghai the 764 officers and men of the Grenadier Battalion of Sardinia further reinforced the Italian Battalion in China, the unit having been transferred from Italian East Africa. Thirty soldiers were directed to defend the consulate building in Shanghai on August 6.

Inevitably, the Italian forces in China were caught up in the Japanese invasion and the light cruiser Montecuccoli was attacked by Japanese aircraft in Shanghai harbour of September 27 and October 24 1937. One crewman was killed and several others injured during these incidents. The attacks created a diplomatic rift between Rome and Tokyo. On December 23 1937 the Montecuccoli was replaced in China by her sister-ship, the Bartolomeo Colleoni, and she stayed in the region until September 1939 when events in Europe demanded her attention. At this juncture, some Italian forces in China, drawn mainly from the air force, Carabinieri (para-military police) and Revenue Guard Corps were repatriated to Italy.

The Italian position in China was assured when Mussolini signed the Tri-partite Pact with Germany and Japan in 1940. This placed Italy in the position of junior partner in the Axis alliance against Great Britain, the Commonwealth, and the British Empire. However, Italian military incompetence proved embarrassing for Hitler, who was forced to commit German forces to the conquest of Greece and North Africa after Italy had suffered severe defeats at the hands of Allied armies throughout 1941-42.

In the Far East the Italian garrison units were unaffected by these events, because following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Japanese forces had soon overwhelmed the lightly defended colonial outposts of Hong Kong, the Dutch East Indies, French Indo-China, Burma and Malaya, culminating in the humiliating surrender of British and Empire forces at Singapore in 1942. Therefore, no Allied forces remained in theatre to pose a threat to Italian interests in the region. However, this is not to say that the Japanese were happy with three areas within important Chinese cities still being firmly under the control of armed and organised Europeans.

Approximately 600 soldiers and sailors, with a further one hundred soldiers and sailors protecting the Italian radio station at Beijing, garrisoned the Italian concession at Tientsin at the time of the September 1943 armistice. The Italians also maintained consulates at Beijing, Hankow (now Hankou) and Shanghai. Located at Tientsin were two gunboats of the Royal Italian Navy, the Lepanto and Carlotto. The naval presence in China and the Far East had been increased during April 1941, when it had become apparent to the Navy High Command that the Italian naval base at Massawa, Eritrea (then part of the colony of Italian East Africa) was going to fall to British forces. The navy had no wish to see its vessels captured by the British, and in February 1941 they had ordered the dispatch of the colonial sloop Eritrea, along with the auxiliary cruisers Ramb 1 and 2 to Kobe, Japan. Ramb 1 was sunk on route by the British cruiser HMS Leander off the Maldives, but the other two vessels eluded Allied patrols and arrived safely in Japan.

At the time of the Italian armistice in 1943, Italian forces were split up all over the Far East. The Italians were participating with the Germans in delivering valuable cargoes of optical instruments, weapons and assorted stores to the Japanese, utilizing their large submarines which had proved disastrous when they had been employed targeting Allied shipping during the Battle of the Atlantic. The Germans had persuaded the Italians to allow their large submarines to be converted into cargo carriers, which proved more useful to the Axis war effort, allowing the Germans to receive large quantities of rubber, quinine, and assorted raw materials from the Japanese (codenamed the Yanagi trade by Japan). The armistice found several Italian submarines in the Far East. In Singapore harbour, the Japanese and Italians had just completed loading the submarines Guiliani and Torelli, both submarine and cargo destined for the German-occupied French port of Bordeaux. In Sabang, another Italian submarine, the Cappellini, was also similarly loaded ready to depart for Europe, and the Cagni was in the Indian Ocean heading for Singapore. As mentioned, moored in Shanghai were the Italian gunboats Lepanto and Carlotto, while in Kobe, Japan an auxiliary cruiser, the Calitea II (formerly Ramb II) was being refitted by the Japanese. Present also in Shanghai was the steamboat Conte Verde.

The armistice placed Italian army and naval units based in the Far East in a dangerous situation. Italy was now fighting for the Allies, and the Italian forces had theoretically become the enemies of the Japanese. For the assorted naval vessels and their crews who now found themselves deep in enemy territory the choice was simple. The fascist followers of Mussolini had pledged to continue to fight on the side of the Axis in northern Italy, and the Italian servicemen trapped in the Far East could have pledged their allegiance to Mussolini and fascism, and sided with the Germans and Japanese, or alternatively they could have surrendered themselves into an uncertain future at the hands of the Japanese. Many naturally chose to continue the fight against the Allies, perhaps to save themselves from internment.

The Eritrea was at sea when the armistice was announced, providing support for Italian submarines conducting the underwater trade between occupied Europe and Japan, and she steamed immediately through the Indian Ocean to Colombo in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), avoiding the Japanese air and sea search for Italian vessels launched at the same time. Some Italian naval vessels determined to preserve the honour of the service, and not allow their ships to be captured by the Japanese. On September 9 1943, in Kobe harbour, the Calitea II was scuttled, an action followed at Shanghai by the Lepanto, Carlotto and Conte Verde. The crews of these vessels were sent to prisoner-of-war camps and used as slave labour by the Japanese for the rest of the war, except those who continued to fight for the Axis cause on the side of the new Italian fascist state.

The Japanese captured three of the remaining Italian submarines, the Cappellini, Guiliani and Torelli, even though the crews had stated that they wished to continue to fight for the Axis. The crews were treated with the same brutality the Japanese had shown to Allied prisoners-of-war, but were eventually reprieved from this terrible situation when their former boats were handed over to the German Navy. The Germans had established a U-boat base at Penang, Malaya, and the Italian sailors continued to serve the Axis cause until the German surrender in May 1945, crewing their former boats alongside German U-boatmen. The submarine Cagni escaped such a fate, and made a dash for South Africa on learning of the armistice, and surrendered to the British. Following the surrender of Nazi Germany, approximately twenty Italian submariners continued working for the Imperial Japanese Navy, and indeed the Torelli continued in Japanese service until August 30 1945, stationed in Japanese home waters. On this day, the anti-aircraft gunners on board the submarine managed to shoot down an American B-25 Mitchell bomber, which, ironically, was the final accredited ‘kill’ scored by a unit of the Japanese navy during the Second World War.

For the Italian military forces stationed on land in China the armistice of September 1943 meant certain internment in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, and surprisingly the Japanese forces sent to disarm and round up these military forces were greeted with resistance. A small mixed army and navy force of one hundred men, under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Baldassare of the Royal Italian Navy, garrisoned the Beijing radio station, within the Italian concession. The Italians were lightly armed with infantry weapons, consisting of the Mannlicher-Carcano M91/38 rifle, Beretta pistols and hand-grenades. Baldasarre determined to defend the radio station against a Japanese infantry regiment numbering approximately one thousand men, supported by artillery and fifteen light tanks. Although outnumbered ten to one, and lacking any heavy weapons, the Italians fought the Japanese forces for over twenty-four hours before surrendering on September 10 1943. Before doing so Baldasarre ordered the radio equipment destroyed, and all secret documentation burned. Incredibly, although the Italians at Beijing had resisted valiantly, afterwards the majority expressed a desire to continue to fight on the Axis side. Only twenty-nine men refused to continue the war against the British and Americans, and these unfortunate officers and men were transported to a prisoner-of-war camp in Korea, where their Japanese captors naturally maltreated them.

The unexpected resistance by so small a group of Italians presumably unsettled the Japanese, whose next task was to disarm and take the surrender of the Italian garrison at Tientsin. This Italian garrison presented a more formidable source of resistance than the composite force the Japanese had encountered at Beijing.

Commander Carlo dell’Acqua’s responsibilities were grave. Because Tientsin was a commercial centre for Italian trade with China, many Italian civilians, including women and children, sought his protection. The routine rape of white women and general maltreatment of non-combatants captured by the Japanese army was well known, and the Italian consul Stefanelli had withdrawn his staff, and the Italian nationals under his care, into an area of the Italian concession that was fortified by dell’Acqua’s men, consisting of the Ermanno Carlotto barracks, the Forum, and the town hall. To defend the concession, dell’Acqua had some six hundred soldiers and sailors under his command. The Italians were considerably better equipped than their comrades at the Beijing radio station, fielding some three hundred rifles, fifty pistols, fifty Breda and Fiat light and medium machine-guns, along with an ammunition supply of two million rounds of various calibre. Importantly, the Italians also had emplaced four 75mm guns, which would have proved more than a match for the Type-96 medium tank used by the Japanese, if utilized in the anti-tank role. Dell’Acqua also possessed four Lancia armoured cars, which would have proved useful against Japanese infantry, and provided the Italian defence with a mobile light armoured reserve to counter any Japanese penetration of the perimeter. There was also a further five ordinary military vehicles within the perimeter. Regarding food, there was also an ample supply of fresh meat, for the Italians possessed around fifty army horses, as well as having a stockpile of regular rations and medicine that would have lasted one week.

Opposing the Italians at Tientsin was Lieutenant-Colonel Tanaka commanding nearly six thousand Japanese troops, reinforced with various types of light armoured vehicles and artillery. Guns had also been deployed on the river to fire into the Italian cantonment, and air support was available in the form of a Japanese Army Air Service bomber squadron stationed close to Beijing. Once again, the Italians were outnumbered ten-to-one, with no hope of relief.

Tanaka did not attack immediately, but instead called upon dell’Acqua to surrender. The Italian officers in charge of the defence conferred, and refused to contemplate surrender. However, they knew that the Japanese forces arrayed against them would shortly be massively reinforced, and they could only hold out in a siege for a limited amount of time before they would have to surrender to spare the civilians under their protection further unnecessary suffering. The Japanese opened a brief artillery barrage upon the Italian cantonment, in order to demonstrate the nature of the battle to come. The Italians also learned that Tanaka was shortly to be reinforced by an entire Japanese division, along with tanks and more artillery, and this persuaded many of the officers that resistance was futile. However, a great majority of the ordinary Italian soldiers and sailors wanted to fight on, but dell’Acqua took the difficult decision to surrender in order to save lives.

The Italian garrison of Tientsin was disarmed and marched into Japanese captivity, with the exception of one hundred and seventy men who decided to pledge their allegiance to the new fascist Italian Social Republic, after the liberation of Mussolini by German paratroopers on September 12 1943. These men fought alongside the Germans and Japanese for the remainder of the war. The remainder of the Tientsin garrison was dispersed to prison camps outside the city, or taken to Korea and Japan, where they suffered alongside other Allied prisoners-of-war until September 1945.