The Hero of Sandakan

An angry roar erupted from the massed Australian POWs as their commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Alf Walsh, his hands bound tightly behind his back, was frog marched by Japanese soldiers over to a wooden post and tied to it. Guards levelled their long bayonet-tipped rifles nervously at the hundreds of prisoners who had taken a few rebellious steps forward towards their commander. Captain Susumi Hoshijima, the camp commandant, smacked Walsh hard across his face with the back of his hand, and a hastily assembled firing squad noisily cocked their rifles.

Just minutes before, the assembled prisoners had witnessed the strutting commandant mount a small platform and order an interpreter to shout out the following order that all prisoners were expected to adhere to: ‘1. We abide by the rules and regulations of the Imperial Japanese Army. 2. We agree not to attempt to escape. 3. Should any of our soldiers escape, we request that you shoot them to death.’ Following this, Walsh mounted the platform and addressed his men. ‘The Japanese are demanding that I, on behalf of you all, sign this statement.’ Pausing dramatically under the boiling tropical sun, Walsh squared his shoulders and announced in a loud and determined voice: ‘I am not ordering anyone to do anything, but I, for one, will not sign such a document.’ The prisoners’ chorus of approval was abruptly terminated by Hoshijima’s violent attack on their commander. This extraordinary scene had been caused by the escape of twelve Australian prisoners from the camp shortly after their arrival at a place that is today synonymous with cruelty and death – Sandakan.

Between May and August 1945 the Japanese forced nearly 3,000 emaciated and diseased British and Australian prisoners of war out of three POW camps that had been established years before outside the small town of Sandakan in the northeast of Borneo. Their Japanese guards systematically and deliberately butchered the Allied prisoners during three large death marches into the island’s rugged jungle interior. The Japanese shot anyone who was unable to keep up with the marching columns. This ugly endnote to the imprisonment of Allied POWs on Borneo has largely overshadowed the story of the Sandakan camps before the massacres. They have also overshadowed a story of enormous courage that was displayed by a small group of Australian prisoners who were led by one of the most determined and unbreakable prisoners, a man who paid the ultimate price for his heroic resistance to the enemy under the most trying of conditions.

The Japanese turned the huge island of Borneo into a giant prison for Allied POWs and civilians. There were camps at Batu Lintang, Kuching, Sarawak, Jesselton, and Sandakan and briefly on Labuan Island.

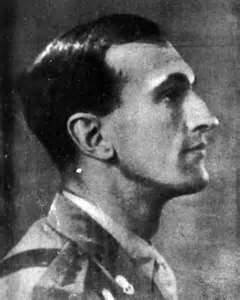

In command at Sandakan was Captain Susumi Hoshijima, an officer with a penchant for brutality, sadism and irrationality in equally disturbing measure. Captain Hoshijima’s greatest nemesis was about to arrive at Sandakan. Lionel Matthews was a 29-year-old decorated captain in the Australian Army Signal Corps from Norwood, Adelaide. Matthews would prove to be a considerable thorn in the side of the Japanese, and a man for whom the words ‘never surrender’ could have been his motto. Matthews had first arrived in Singapore on Valentines Day 1941 as part of the Major General H. Gordon Bennett’s much vaunted 8th Australian Division. The brown-haired, blue-eyed former department store salesman who sported a neatly trimmed moustache quickly impressed his superiors during the Battle of Gemas, one of the bloody engagements fought by the Australians during the retreat down the Malay Peninsula. Then Lieutenant Matthews went out under heavy Japanese artillery and mortar fire to restore communications between his brigade headquarters and its subordinate units. He also ‘succeeded in laying cable over ground strongly patrolled by the enemy and thus restoring communication between his Divisional HQ and the HQ of a Brigade at a critical period.’ Awarded the Military Cross, Matthews was promoted to captain in January 1942. Captured when General Percival surrendered Singapore in February 1942, Matthews was initially imprisoned at the infamous Changi Camp. Back in Australia his wife Lorna and young sons heard little of his activities, or of his ultimate fate, until 1945.

At Sandakan, Matthews did not view his circumstances as a reason to stop fighting the Japanese. Within a harsh and terrifying environment Matthews began to create an organisation that would eventually pose a serious threat. Hoshijima strictly forbade any communication between the three camps, and anyone who disobeyed this order was severely punished. Matthews first task was to break Hoshijima’s prohibition on inter-camp communication by setting up a secret network. He also began to address the central problems that were faced by the POWs, namely a lack of medicines to treat the various tropical diseases that stalked them more efficiently than their guards, as well as a shortage of food. Matthews’ efforts in smuggling food into the camps through his contacts with locals went some way to alleviating chronic malnutrition. Matthews could only do this by building contacts with the world beyond the perimeter fence, a decidedly dangerous undertaking as he never knew for sure who could be trusted and who would have turned them over to the Japanese in return for cash.

The Japanese allowed Matthews to command a small group of prisoners who were permitted outside unsupervised by guards to collect nuts. A grove of palm-oil trees behind the local police station became Matthews’ connection point to the local underground resistance movement. The police put Matthews in touch with local British doctor Jim Taylor, one of several medics and dentists that the Japanese had not interned because their skills were desperately needed. Although under close watch, Taylor risked his life smuggling medicines to the camps, along with another civilian, Lillian Funk. This intrepid lady had wisely converted some of her assets to gold, pearl, foreign currency and gemstones just before the Japanese had captured Sandakan, and she had sewn these valuables into the hems of her clothes. She sold what she needed to purchase food and medicines for the POWs, and also maintained a link with Philippine guerrillas.

Matthews organized a group of twenty trusted officers and NCOs into an ad hoc intelligence-gathering group. Using sympathetic local intermediaries, Matthews’ group made contact with British civilians being held in an internment camp on nearby Bahara Island. Natives often entered the camps to perform various menial chores, and British and Australian working parties outside the camps also had contact with locals. At the civilian camp on Bahara Island was Charles Smith, the former Governor of North British Borneo. Smith immediately realised the value of Matthews’ intelligence work and appointed him secret commander of the North British Armed Constabulary, a native police force that remained in operation under Japanese control. Many of its officers and men remained loyal to the British. Many locals were of Chinese descent, and their treatment by the Japanese was harsh and discriminatory, engendering great hatred. Many were happy to help the British war effort if it meant an end to the Japanese occupation. Matthews built up a dossier of intelligence concerning the organization and deployment of Japanese forces in North Borneo, their strengths and bases, supply situation and details about the local geography. Matthews intended to pass all of this valuable information on to the Allies in the hope that it would assist them in eventually liberating Borneo.

The gathering and caching of firearms was another of Matthews’ efforts, the intention eventually being to launch an insurrection most probably timed to coincide with an Allied invasion. Matthews’ group needed information about the progress of the war, so using their network they managed to smuggle radio parts into their camp and constructed a simple wireless receiver. It was a mission fraught with danger, but two Australian officers, Lieutenant Rod Wells and Lieutenant Gordon Weynton, put together the crystal detector, valves and headphones.

The job of getting a signal on the basic wireless took weeks of effort, but one day through the crackling static came a familiar English public school voice that confidently announced: ‘This is the BBC’. Barely able to contain his excitement, Matthews ordered the delicate set wrapped in a waterproof groundsheet and carefully hidden inside an unused latrine pit. A system of nocturnal radio monitoring was set up, whereby news was carefully written down by the listeners and then distributed to the POW officers, who in turn passed it on verbally to their men, raising morale.

Matthews knew that it was important to demonstrate to the locals that the war was turning against the Japanese, to secure their continued support for his secret activities. Russ Ewin was tasked with passing the latest bulletins to the resistance. ‘The police station was the contact for me. I would report each day to Lionel. If he had anything to be taken out of the camp, I would take it,’ recalled Ewin. The risk of being caught on one of these missions did not bear thinking about. Ewin would most probably have been horribly tortured by the Kempeitai and then shot. ‘It usually was the news,’ said Ewin of the packages that Lionel gave him, ‘and it was rolled up tightly in a wad of paper sealed with sealing wax. When we came to the police station, I would just nod my head slightly, and the police sergeant, Sergeant Abin, who I had met, would just watch my hand and I would open it and drop the news. He would pick it up afterwards…’

This operation went smoothly, but what he heard on the radio emboldened Matthews to pursue another plan that unfortunately proved to be his undoing. Any uprising that was going to be made by the remaining fit prisoners, the members of the Constabulary and other sympathizers needed to be carefully timed. Matthews knew the prisoners needed a radio transmitter so they could communicate directly with the Allies as their current wireless was only a receiver. The process of smuggling the parts into the camp began, but the fundamental weakness of Matthews’s organisation was the large number of people involved outside of the wire. Unfortunately, one of the Chinese sympathizers who procured radio parts, Joe Ming, was betrayed to the Kempeitai by a disgruntled contact. The Kempeitai moved with their customary swiftness to destroy the ‘resistance organisation’ and brutally tortured Ming and his family until they broke and started talking.

For Matthews and some of his men the game was up. He had long known the terrible risks that he was running, but his sense of duty had outweighed any concerns that he may have had for his own personal safety or survival. ‘He was in a position where he could have escaped on numerous occasions by means of help of an organisation set up by the Chinese but he declined, electing to remain where his efforts could alleviate the sufferings of his fellow prisoners.’ The Allied conspirators that had been named by Joe Ming, including some local men, were removed to Kempeitai headquarters in Kuching. For three long and terrible months Matthews and his friends were horribly tortured. They endured vicious beatings, including the infamous ‘water treatment’. They were hung by the arms for long periods and had their fingernails pulled off with pliars. One of their number, Johnny Funk, whose wife Lillian had sold gold and pearls to buy medicine for the prisoners, recalled: ‘They had four bungalows which were used for torture rooms. One form of torture was to make you kneel on a plank specially carved like spikes. They then placed a heavy plank behind the knees and two Japanese got on each and worked it like a see-saw.’ The Kempeitai was inventive in the methods it employed. ‘Another torture was carried out by a Jujitsu expert. He flung you all around the room. He badly twisted limbs and used his boots freely,’ said Funk. ‘I was also jammed in a specially constructed chair, in a cramped position. For half a day I was whipped around the head.’

Captain Matthews and the others managed to resist all Japanese efforts to make them talk. All the Japanese had by way of evidence was the ‘crime’ of possession of an illegal wireless set and some vague notion that these men had been plotting against the occupation forces. The Kempeitai arrested and tortured fifty-two civilians and twenty POWs, accounting for virtually Matthews’ entire network and a good proportion of the local underground as well.

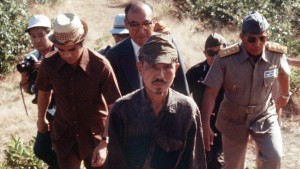

Those arrested ended up in Kuching. Gordon Weynton was found guilty of ‘spreading rumours’ and sentenced to ten years imprisonment. Lieutenant Wells received twelve years hard labour, to be served in solitary confinement. Both officers were transported to Outram Road Jail in Singapore to serve out their sentences, saving them from the Sandakan Death Marches in 1945. As for Matthews, his fate was sealed the moment he was captured. The court sentenced him to death by firing squad.

On 2 March 1944, alongside eight of the other ringleaders, Matthews faced his execution with great courage. ‘He left Australia nearly 16 stone and he was only 6 stone at the end’ said his son David of the father he never knew. Matthews declined a blindfold and looked his Japanese executioners square in the face. He was posthumously awarded the George Cross for his immense courage and resourcefulness in captivity, the very highest award available to Commonwealth citizens for valour that was not performed in battle.