Japanese Jungle Holdouts

Mark Felton

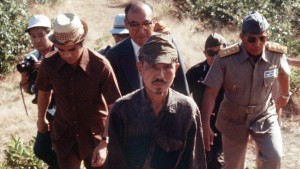

A small, thin, middle-aged officer, his uniform patched and darned, his field service cap emblazoned with the yellow star of the Imperial Japanese Army, stepped forward in a jungle clearing and bowed stiffly before lifting up his samurai sword and offering it to the assembled officials in surrender. The place was the island of Lubang in the Philippines and the date was 9 March 1974. Fifty-one-year-old Second Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda had finally given up resistance. The last thing his commanding officer had said to him was ‘Whatever happens, we’ll come back for you.’ Twenty-nine years later the Japanese returned. Onoda was one of the last recorded Japanese ‘holdouts’, living relics of a war that had ended nearly three decades before. While the world had moved into the Cold War, Onoda and others like him had remained hidden in the jungle, convinced World War II was still being fought.  When Japan surrendered in August 1945, the Imperial Army and Navy still controlled a vast swathe of Asia including eastern China, Malaya, Singapore, Netherlands East Indies and dozens of far-flung tropical island groups garrisoned by three million troops. Most knew nothing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They were well-armed and mentally conditioned to fight on to eventual victory or an honourable death. Surrender was anathema to them. Orders were transmitted to units telling them to stay in their barracks and await the arrival of Allied forces who would take their formal surrenders. But tens of thousands of Japanese troops never received the order as their communications with Japan had broken down or their units had been smashed and scattered during the fierce battles across the Pacific. Others, including complete units, refused to believe that such a shameful order could have emanated from their divine Emperor Hirohito – these diehards believed it was an Allied trick. They determined to stay in the jungle and wait for their army to recapture the lost territories. Between 1945 and 1961 many of these ‘holdouts’ were caught or convinced to surrender by Japanese officials. What is not widely known is that some Japanese units and stragglers even launched attacks on American occupation forces or the armies of the newly independent postwar nations necessitating dangerous operations to capture or kill them. One of the most notorious was Captain Sakae Oba on Saipan, who continued to lead his 46 heavily armed men in attacks on US forces until convinced to surrender by a former Japanese general in December 1945. On another occasion in the mountains south of Manila on 25 January 1946 American and Filipino forces mounted a joint operation to eliminate a 120-man Japanese unit. In the vicious fighting that followed 72 Japanese were killed. In Lubang, Philippines, a 30-man Japanese unit was brought to battle on 22 February 1946. Eight Allied soldiers died along with an unknown number of Japanese. The following month a further 41 Japanese soldiers emerged on Lubang and surrendered, eight months after the war had ended. On Peleliu a 33-man Japanese force attacked American patrols throughout March and early April 1947 until persuaded to surrender by a former Japanese admiral.

When Japan surrendered in August 1945, the Imperial Army and Navy still controlled a vast swathe of Asia including eastern China, Malaya, Singapore, Netherlands East Indies and dozens of far-flung tropical island groups garrisoned by three million troops. Most knew nothing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They were well-armed and mentally conditioned to fight on to eventual victory or an honourable death. Surrender was anathema to them. Orders were transmitted to units telling them to stay in their barracks and await the arrival of Allied forces who would take their formal surrenders. But tens of thousands of Japanese troops never received the order as their communications with Japan had broken down or their units had been smashed and scattered during the fierce battles across the Pacific. Others, including complete units, refused to believe that such a shameful order could have emanated from their divine Emperor Hirohito – these diehards believed it was an Allied trick. They determined to stay in the jungle and wait for their army to recapture the lost territories. Between 1945 and 1961 many of these ‘holdouts’ were caught or convinced to surrender by Japanese officials. What is not widely known is that some Japanese units and stragglers even launched attacks on American occupation forces or the armies of the newly independent postwar nations necessitating dangerous operations to capture or kill them. One of the most notorious was Captain Sakae Oba on Saipan, who continued to lead his 46 heavily armed men in attacks on US forces until convinced to surrender by a former Japanese general in December 1945. On another occasion in the mountains south of Manila on 25 January 1946 American and Filipino forces mounted a joint operation to eliminate a 120-man Japanese unit. In the vicious fighting that followed 72 Japanese were killed. In Lubang, Philippines, a 30-man Japanese unit was brought to battle on 22 February 1946. Eight Allied soldiers died along with an unknown number of Japanese. The following month a further 41 Japanese soldiers emerged on Lubang and surrendered, eight months after the war had ended. On Peleliu a 33-man Japanese force attacked American patrols throughout March and early April 1947 until persuaded to surrender by a former Japanese admiral.  And so it continued all over Asia in the immediate aftermath of the war. In the Philippines in April 1947 a seven-man Japanese heavy mortar team emerged from the jungle on Palawan Island and surrendered, and in the same month on Luzon fifteen Japanese troops finally gave up. Four-and-a-half years after the Americans had captured Guadalcanal in the British Solomon Islands, the last Japanese soldier finally emerged from the interior and surrendered on 27 October 1947. The last sizeable Japanese unit to surrender was on Mindanao in the Philippines. Two hundred troops were persuaded to give up in January 1948, surrendering well-maintained rifles and machine guns.

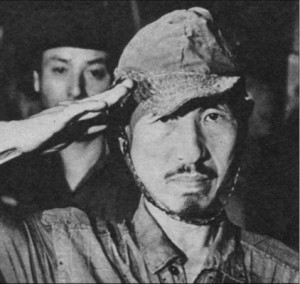

And so it continued all over Asia in the immediate aftermath of the war. In the Philippines in April 1947 a seven-man Japanese heavy mortar team emerged from the jungle on Palawan Island and surrendered, and in the same month on Luzon fifteen Japanese troops finally gave up. Four-and-a-half years after the Americans had captured Guadalcanal in the British Solomon Islands, the last Japanese soldier finally emerged from the interior and surrendered on 27 October 1947. The last sizeable Japanese unit to surrender was on Mindanao in the Philippines. Two hundred troops were persuaded to give up in January 1948, surrendering well-maintained rifles and machine guns.  In New Guinea, site of the valiant Australian defence of the Kokoda Track in 1942 and the battles around Port Moresby, local police apprehended eight Japanese soldiers in 1950. They were survivors of a division that had been destroyed during the Battle of Finschhafen in September and October 1943 and the retreat of the starving Japanese towards Madang. They had hidden in the dense jungle for seven years. Then, four years later in 1954 New Guinea police captured another four Japanese holdouts, the last survivors of a group of 89 Japanese who had forced marched from Wewak to Hollandia in April 1944. Their companions had all died of disease or starvation in the jungle. During the 1950s, as Japan rebuilt its economy and emerged as a deeply pacifist country, these jungle holdouts were not viewed as fanatics but as victims of the war. The soldiers captured in New Guinea were portrayed in Japan as exotic beings, ‘jungle men’. By 1955 this view had altered slightly, notes historian Beatrice Trefault, and the Japanese viewed them as soldiers, ‘but not just plainly, as living heroes but as a moving image of the fallen soldier, in other words, as ‘dead soldiers’ accidentally and unexpectedly alive.’ Later, as more soldiers appeared throughout the 1970s, the Japanese public’s perception of them changed still further and they began to be seen as heroic examples of endurance and courage to the younger postwar generation. The 1960s was relatively quite and only two Japanese holdouts emerged on Guam and surrendered in 1961. They had held out for an amazing sixteen years. But if the Japanese and the rest of the world thought that the phenomenon was over they were astounded when, in 1972, after a staggering twenty-eight years in hiding, a single holdout turned up alive on Guam. Corporal Shoichi Yokoi’s discovery hit the headlines around the world. Yokoi, of the 38th Infantry Regiment, had fled into the jungle in July 1944 along with many other stragglers following the American victory. As we have seen many of these troops surrendered in the 1940s, ‘50s and early ‘60s, or they had died of injuries, illness or starvation. Yokoi and two comrades had constructed an underground hiding place and subsisted for years on a diet of seafood and coconuts. Sometime during the 1960s the two other soldiers who were with Yokoi moved away and later died of starvation. Yokoi stayed hidden, putting his pre-war tailoring skills to use by making himself a new uniform out of tree bark. Two local hunters fishing on the Talofofo River in January 1972 discovered him. Yokoi, like many other holdouts, had seen leaflets announcing the Japanese surrender dropped by American aircraft in the 1940s, but he believed them to be a trick and decided to stay in hiding. His unaltered wartime psyche was demonstrated when he was returned with considerable media coverage to Japan. He stated: ‘It is with much embarrassment that I return.’ Yokoi said that he wished to return his rusty and useless Arisaka rifle to ‘the Honourable Emperor. I am sorry I did not serve His Majesty to my satisfaction.’ Yokoi’s rehabilitation was swift and impressive considering that he had spent almost three decades subsisting in the jungle. He married, became a TV presenter and even ran for parliament in 1974. In 1991 he was granted an audience with Emperor Akihito during which he said that he regretted having failed to serve the Imperial Army well and was overcome with emotion. Yokoi died in 1997. The Japanese government became so concerned that other middle-aged men like Corporal Yokoi might still be in hiding in Southeast Asia that they created a special unit to look for them from officials at the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The most famous holdout of all emerged from the jungles of Lubang and surrendered in March 1974. Second Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda was very different from Yokoi because he had continued a violent guerrilla campaign that caused several deaths and substantial military and police operations for thirty years. ‘Every Japanese soldier was prepared for death, but as an intelligence officer I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die,’ said Onoda in 2011. ‘I had to follow my orders as I was a soldier’. He took a small team of Japanese soldiers into the island’s interior and waged an aggressive campaign that last almost 30 years. Along with Corporal Shoichi Shimada, Private First Class Yuichi Akatsu and Private Kinshichi Kozuka, Onoda constantly moved his command every five days to avoid capture, the men living off bananas, water buffalo, wild boar, chickens and iguanas. Occasionally Onoda and his men would emerge from their mountainous jungle hideouts to shoot cows owned by local Philippine peasants. This was always risky because the gunfire attracted local police and on several occasions the Japanese holdouts were fired at. In 1949 Private Akatsu decided to leave the group after an argument. Onoda thought that he would starve to death but Akatsu managed to survive for six months on his own before he surrendered to a Philippine Army patrol. Later Onoda discovered a note from Akatsu that stated that the war was over and the Philippine troops were friendly. Akatsu led soldiers into the mountains in 1950 in an attempt to locate Onoda’s group and persuade them to surrender. They never found them. Onoda considered Akatsu to be a traitor and working for the enemy. In 1952 the Philippine and Japanese governments made a further attempt to locate and capture Onoda’s group. Letters and photographs from the holdouts’ families were dropped over the jungle. ‘The leaflets they dropped were filled with mistakes so I judged it was a plot by the Americans,’ said Onoda. In June 1953 Corporal Shimada was shot and wounded in the leg by local fishermen when the group was on one of its regular village raids. Onoda and Private Kozuka nursed Shimada back to health but the corporal was killed during a firefight with searchers on 7 May 1954. Onoda and Kozuka continued to raid local settlements for supplies, often burning the harvested rice and shooting at local peasants. It has been estimated that Onoda’s depredations killed or wounded around thirty Filipinos over the decades. On 19 October 1972 the two holdouts were busy burning rice stocks in a village when armed police arrived. During the following gunfight Kozuka was hit twice and killed. Onoda fled into the jungle vowing to kill anyone who came after him. A Japanese student and adventurer, Norio Suzuki, set out to find Onoda in 1974. It seemed unlikely that he would succeed where governments and armies had failed, but camping alone within Onoda’s ‘territory’ he managed to strike up a hesitant friendship with the Japanese officer. Suzuki persuaded Onoda to come to a parley in a jungle clearing to meet with Japanese and Filipino representatives. At the meeting Onoda stated that he could not surrender until he had received a direct order from his superior, and he went back into hiding. Finally, on 9 March 1974, Lieutenant Onoda met with former Major Taniguchi, his old commander on Lubang, who ordered him to hand over his samurai sword and surrender with honour. Hiroo Onoda, still the punctilious officer that he had been in 1945, immediately obeyed. Onoda was very well armed and surrendered his sword as well as a functioning Arisaka Type-99 rifle, 500 rounds of ammunition, several hand grenades and a commando dagger. On his return to Japan Onoda became something of a celebrity. He was different from other recently returned holdouts – he had been an officer and he had not stopped fighting, however misguided his resistance had ultimately been. This living relic from the war may have impressed modern Japan but the modern Japanese did not impress Onoda. ‘Japan’s philosophy and ideas changed dramatically after World War II. That philosophy clashed with mine so I went to live in Brazil.’ Now aged 90, Onoda lives in Japan but spends three months of every year in Brazil and was honoured with a medal by the Brazilian Air Force in 2004. In 1996 Onoda controversially returned to Lubang and donated US$10,000 to a local school, perhaps as recompense for the harm he and his men caused during their three-decade terror campaign. When asked why he held out for so long, Onoda’s single-mindedness was plain: ‘I became an officer and I received an order. If I could not carry it out, I would feel shame.’ Within months of Onoda’s capture reports started to filter in from Morotai in Indonesia where locals had reported Japanese soldiers hiding in the forest for decades. The Japanese government set up loudspeakers around the island’s mountainous interior and blasted the area with the wartime Japanese national anthem. Then, in October 1974 an Indonesian Air Force pilot spotted a small hut hidden in the jungle. Two months later Private Teruo Nakamura of the 4th Takasago Volunteer Unit emerged from hiding armed with a functioning rifle and his last five rounds of ammunition and surrendered to local troops. He had no idea that the war was over and had long believed that he would be killed if captured. He had built a small hut in the forest set on a 20-by-30 metre fenced field. Nakamura, a native conscripted Formosan chose to return directly to Taiwan. His capture did not excite the Japanese media – Onoda was a Japanese officer whereas Nakamura was a conscript from a former Japanese colony. Nakamura died of lung cancer in 1979. Since Onoda’s surrender reports have continued to surface almost up to the present day of Japanese holdouts. In 1980 it was widely reported that a Captain Fumio Nakahira had been discovered on Mindoro after 36 years in hiding. This story proved to be a fake. In 1989 on the Pacific island of Vella Lavella locals reported that old Japanese soldiers had been pilfering food and supplies for decades. These stories were probably hoaxes designed to lure rich Japanese tourists to the island. In 1992 on Kolombangara, an island north of New Georgia that was bypassed by American forces in 1943 during the island hopping campaign, locals reported two or three elderly Japanese holdouts. Although searches of the mountains and jungle were conducted, no evidence was found. Most recently, in 2001, holdouts were reported on Guadalcanal, but again no concrete evidence has been discovered since the last Japanese surrendered there in 1947. Many Japanese soldiers undoubtedly remained in hiding throughout Asia and the Pacific into the 1970s and they were never found. Perhaps a few managed to survive into more recent times until disease, accidents or old age carried them off. We may never know the full extent of the Japanese holdouts phenomenon, nor fully understand why Japanese soldiers behaved as they did, but clearly the Japanese soldier remained a formidable, tough and single-minded adversary, even many decades after defeat.

In New Guinea, site of the valiant Australian defence of the Kokoda Track in 1942 and the battles around Port Moresby, local police apprehended eight Japanese soldiers in 1950. They were survivors of a division that had been destroyed during the Battle of Finschhafen in September and October 1943 and the retreat of the starving Japanese towards Madang. They had hidden in the dense jungle for seven years. Then, four years later in 1954 New Guinea police captured another four Japanese holdouts, the last survivors of a group of 89 Japanese who had forced marched from Wewak to Hollandia in April 1944. Their companions had all died of disease or starvation in the jungle. During the 1950s, as Japan rebuilt its economy and emerged as a deeply pacifist country, these jungle holdouts were not viewed as fanatics but as victims of the war. The soldiers captured in New Guinea were portrayed in Japan as exotic beings, ‘jungle men’. By 1955 this view had altered slightly, notes historian Beatrice Trefault, and the Japanese viewed them as soldiers, ‘but not just plainly, as living heroes but as a moving image of the fallen soldier, in other words, as ‘dead soldiers’ accidentally and unexpectedly alive.’ Later, as more soldiers appeared throughout the 1970s, the Japanese public’s perception of them changed still further and they began to be seen as heroic examples of endurance and courage to the younger postwar generation. The 1960s was relatively quite and only two Japanese holdouts emerged on Guam and surrendered in 1961. They had held out for an amazing sixteen years. But if the Japanese and the rest of the world thought that the phenomenon was over they were astounded when, in 1972, after a staggering twenty-eight years in hiding, a single holdout turned up alive on Guam. Corporal Shoichi Yokoi’s discovery hit the headlines around the world. Yokoi, of the 38th Infantry Regiment, had fled into the jungle in July 1944 along with many other stragglers following the American victory. As we have seen many of these troops surrendered in the 1940s, ‘50s and early ‘60s, or they had died of injuries, illness or starvation. Yokoi and two comrades had constructed an underground hiding place and subsisted for years on a diet of seafood and coconuts. Sometime during the 1960s the two other soldiers who were with Yokoi moved away and later died of starvation. Yokoi stayed hidden, putting his pre-war tailoring skills to use by making himself a new uniform out of tree bark. Two local hunters fishing on the Talofofo River in January 1972 discovered him. Yokoi, like many other holdouts, had seen leaflets announcing the Japanese surrender dropped by American aircraft in the 1940s, but he believed them to be a trick and decided to stay in hiding. His unaltered wartime psyche was demonstrated when he was returned with considerable media coverage to Japan. He stated: ‘It is with much embarrassment that I return.’ Yokoi said that he wished to return his rusty and useless Arisaka rifle to ‘the Honourable Emperor. I am sorry I did not serve His Majesty to my satisfaction.’ Yokoi’s rehabilitation was swift and impressive considering that he had spent almost three decades subsisting in the jungle. He married, became a TV presenter and even ran for parliament in 1974. In 1991 he was granted an audience with Emperor Akihito during which he said that he regretted having failed to serve the Imperial Army well and was overcome with emotion. Yokoi died in 1997. The Japanese government became so concerned that other middle-aged men like Corporal Yokoi might still be in hiding in Southeast Asia that they created a special unit to look for them from officials at the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The most famous holdout of all emerged from the jungles of Lubang and surrendered in March 1974. Second Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda was very different from Yokoi because he had continued a violent guerrilla campaign that caused several deaths and substantial military and police operations for thirty years. ‘Every Japanese soldier was prepared for death, but as an intelligence officer I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die,’ said Onoda in 2011. ‘I had to follow my orders as I was a soldier’. He took a small team of Japanese soldiers into the island’s interior and waged an aggressive campaign that last almost 30 years. Along with Corporal Shoichi Shimada, Private First Class Yuichi Akatsu and Private Kinshichi Kozuka, Onoda constantly moved his command every five days to avoid capture, the men living off bananas, water buffalo, wild boar, chickens and iguanas. Occasionally Onoda and his men would emerge from their mountainous jungle hideouts to shoot cows owned by local Philippine peasants. This was always risky because the gunfire attracted local police and on several occasions the Japanese holdouts were fired at. In 1949 Private Akatsu decided to leave the group after an argument. Onoda thought that he would starve to death but Akatsu managed to survive for six months on his own before he surrendered to a Philippine Army patrol. Later Onoda discovered a note from Akatsu that stated that the war was over and the Philippine troops were friendly. Akatsu led soldiers into the mountains in 1950 in an attempt to locate Onoda’s group and persuade them to surrender. They never found them. Onoda considered Akatsu to be a traitor and working for the enemy. In 1952 the Philippine and Japanese governments made a further attempt to locate and capture Onoda’s group. Letters and photographs from the holdouts’ families were dropped over the jungle. ‘The leaflets they dropped were filled with mistakes so I judged it was a plot by the Americans,’ said Onoda. In June 1953 Corporal Shimada was shot and wounded in the leg by local fishermen when the group was on one of its regular village raids. Onoda and Private Kozuka nursed Shimada back to health but the corporal was killed during a firefight with searchers on 7 May 1954. Onoda and Kozuka continued to raid local settlements for supplies, often burning the harvested rice and shooting at local peasants. It has been estimated that Onoda’s depredations killed or wounded around thirty Filipinos over the decades. On 19 October 1972 the two holdouts were busy burning rice stocks in a village when armed police arrived. During the following gunfight Kozuka was hit twice and killed. Onoda fled into the jungle vowing to kill anyone who came after him. A Japanese student and adventurer, Norio Suzuki, set out to find Onoda in 1974. It seemed unlikely that he would succeed where governments and armies had failed, but camping alone within Onoda’s ‘territory’ he managed to strike up a hesitant friendship with the Japanese officer. Suzuki persuaded Onoda to come to a parley in a jungle clearing to meet with Japanese and Filipino representatives. At the meeting Onoda stated that he could not surrender until he had received a direct order from his superior, and he went back into hiding. Finally, on 9 March 1974, Lieutenant Onoda met with former Major Taniguchi, his old commander on Lubang, who ordered him to hand over his samurai sword and surrender with honour. Hiroo Onoda, still the punctilious officer that he had been in 1945, immediately obeyed. Onoda was very well armed and surrendered his sword as well as a functioning Arisaka Type-99 rifle, 500 rounds of ammunition, several hand grenades and a commando dagger. On his return to Japan Onoda became something of a celebrity. He was different from other recently returned holdouts – he had been an officer and he had not stopped fighting, however misguided his resistance had ultimately been. This living relic from the war may have impressed modern Japan but the modern Japanese did not impress Onoda. ‘Japan’s philosophy and ideas changed dramatically after World War II. That philosophy clashed with mine so I went to live in Brazil.’ Now aged 90, Onoda lives in Japan but spends three months of every year in Brazil and was honoured with a medal by the Brazilian Air Force in 2004. In 1996 Onoda controversially returned to Lubang and donated US$10,000 to a local school, perhaps as recompense for the harm he and his men caused during their three-decade terror campaign. When asked why he held out for so long, Onoda’s single-mindedness was plain: ‘I became an officer and I received an order. If I could not carry it out, I would feel shame.’ Within months of Onoda’s capture reports started to filter in from Morotai in Indonesia where locals had reported Japanese soldiers hiding in the forest for decades. The Japanese government set up loudspeakers around the island’s mountainous interior and blasted the area with the wartime Japanese national anthem. Then, in October 1974 an Indonesian Air Force pilot spotted a small hut hidden in the jungle. Two months later Private Teruo Nakamura of the 4th Takasago Volunteer Unit emerged from hiding armed with a functioning rifle and his last five rounds of ammunition and surrendered to local troops. He had no idea that the war was over and had long believed that he would be killed if captured. He had built a small hut in the forest set on a 20-by-30 metre fenced field. Nakamura, a native conscripted Formosan chose to return directly to Taiwan. His capture did not excite the Japanese media – Onoda was a Japanese officer whereas Nakamura was a conscript from a former Japanese colony. Nakamura died of lung cancer in 1979. Since Onoda’s surrender reports have continued to surface almost up to the present day of Japanese holdouts. In 1980 it was widely reported that a Captain Fumio Nakahira had been discovered on Mindoro after 36 years in hiding. This story proved to be a fake. In 1989 on the Pacific island of Vella Lavella locals reported that old Japanese soldiers had been pilfering food and supplies for decades. These stories were probably hoaxes designed to lure rich Japanese tourists to the island. In 1992 on Kolombangara, an island north of New Georgia that was bypassed by American forces in 1943 during the island hopping campaign, locals reported two or three elderly Japanese holdouts. Although searches of the mountains and jungle were conducted, no evidence was found. Most recently, in 2001, holdouts were reported on Guadalcanal, but again no concrete evidence has been discovered since the last Japanese surrendered there in 1947. Many Japanese soldiers undoubtedly remained in hiding throughout Asia and the Pacific into the 1970s and they were never found. Perhaps a few managed to survive into more recent times until disease, accidents or old age carried them off. We may never know the full extent of the Japanese holdouts phenomenon, nor fully understand why Japanese soldiers behaved as they did, but clearly the Japanese soldier remained a formidable, tough and single-minded adversary, even many decades after defeat.