A Mosquito fighter-bomber roared down towards the long train that snaked through the dark forest of Eastern Germany. Behind the aircraft several more followed in tight formation, each driving home devastating attacks. The British aircraft, armed with bombs, rockets and cannon, screamed along the length of the train. Two steam engines hauled smart Pullman carriages at almost full speed. Cannon shells ripped through the surrounding treetops, or thudded like crazed hornets into the roofs of the carriages, gouging out great holes. Rockets and bombs smashed down, the train rocking as blasts impacted close by, uprooting trees and throwing huge showers of dirt high into the air. German anti-aircraft crews fed box after box of 20mm shells into the four-barrel guns mounted on special carriages at each end of the train, a constant barrage peppering the sky with black puffs of smoke. One-by-one the Mosquitos dove on the train, expending their munitions, many taking shrapnel hits from the intense flak screen, one peeling away with its port engine on fire before ploughing into the surrounding forest in a massive fireball. But, suddenly the leading locomotive’s boiler exploded as RAF cannon shells punched through it, and the train started to slow down. More Mosquitos piled in, one scoring a direct hit with a bomb on a carriage midway down the length of the train, its metal body absorbing the hit, the interior instantly reduced to a burning charnel house of wrecked furniture and smashed bodies. The train was strafed from end to end before a British air-to-ground rocket slammed into the second carriage, severely wounding Hitler and his closest staff who were crouched beneath the conference room’s wooden table. RSD personnel fought their way into the burning carriage with fire extinguishers before rescuing their boss who had severe shrapnel wounds to the head and chest. As the last of the British aircraft made a pass, the train came to a shuddering halt while onboard the doctors desperately tried stem the Führer’s bleeding and the heavily armed RSD organized a hasty evacuation to the nearest town.

The preceding never happened, but the scenario was one of three plans hatched by the British to kill Hitler whilst he was aboard his personal train. The others were to detail it with explosives or poison its drinking water supply. Hitler continued to use his train until the last few weeks of the war even though the Allies had air superiority over the Reich, a move that was seen by many as an unnecessary security risk. Special Operations Executive, ingenious as ever, saw Hitler’s train as the perfect target but in the end the British failed to launch an assault on the Fuhrer Special.

Throughout the war Hitler travelled constantly. He used three methods to get around his empire: planes, trains and cars. As his security became more professional it was deemed important that Hitler no longer use public transport, where he would be vulnerable to assassination. Instead, the security agencies that protected the Führer began to acquire private means of transport that eventually resulted in Hitler being able to travel widely without having any contact with his people or those outside of his inner circle of advisors and generals. One of his favourite modes of transport was the train, and Hitler’s train was a truly awesome sight.

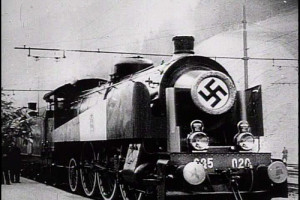

Emperor Wilhelm II had had the use of several plush railway carriages that formed an Imperial Train before the end of the First World War. The German government during the Weimar period then re-used some of these carriages. Hitler ordered the construction of several special coaches between 1937 and 1939 for his own train. Each coach was constructed entirely from steel and weighed over 60 tons. The Führersonderzug, as Hitler’s train was known, came in two configurations – peacetime and wartime. The peacetime train consisted (in order) of a locomotive, baggage and power engine car, Führer’s Pullman, conference car, escort car, dining car, two sleeping cars, Pullman coach, personnel car, press chief’s car, baggage and power-engine car. Codenamed ‘Amerika’ until 31 January 1943, it was then renamed ‘Brandenburg’. During wartime Hitler’s train was officially an Führerhauptquartier (Führer Headquarters – FHQ).

An FHQ, whether a mobile train or static headquarters complex, was a command facility for Hitler’s use. The Wehrmacht always had its own headquarters nearby and liaison officers seconded to the FHQ. But the FHQ was not a military headquarters in the strictest sense, but rather was de facto because of Hitler’s interference in the military command structure.

The Army, Navy and Air Force had received nominal oversight since 1938 by one unified organisation, the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Supreme Command of the Armed Forces – OKW). For most of the war Generalfeldmarshall Wilhelm Keitel acted as its commander, with Generaloberst Alfred Jodl as Chief of Operations Staff. In reality Hitler personally controlled OKW.

The German Army was under the command of Oberkommando des Heeres (Supreme Command of the Army – OKH), headed until December 1941 by Generaloberst Walther von Brauchitsch. Hitler sacked him after he failed to capture Moscow and appointed himself Supreme Commander of OKH. During wartime, OKH was responsible for strategic planning of Armies and Army Groups and the OKH General Staff managed operational matters. Both OKH and OKW were co-located in a huge bunker complex at Zossen outside Berlin, and both had large numbers of staff officers and adjutants attached to FHQ.

Little is known today about Hitler’s wartime train, but an idea of its likely regular composition comes from information leaked in June 1941, when the Führersonderzug departed the Anhalter Station in Berlin for Hitler’s gloomy pine forest HQ at Rastenburg in East Prussia. For the overnight journey the train consisted of fifteen carriages pulled by two large Deutsches Bahn K5E series war locomotives. The Führersonderzug was a self-contained rolling headquarters that enabled Hitler, much like the present British Royal Family and their Royal Train, to travel in safety and comfort to any part of his empire whilst remaining wired in to the communications grid. If the train stopped, the Führer’s Pullman, dining car and sleeping cars could be quickly connected with the postal telephone network. When on the move, communications were conducted by encrypted radio.

Behind the two locomotives was a flatbed Flakwagen mounting two Flakvierling 38 four-gun anti-aircraft cannon manufactured by Mauser. Sitting on a traversing platform, the Flakvierling 38 consisted of four individual 0.78 in (20mm) cannons mounted together that were each fed by twenty round magazines. In combat, the Flakvierling 38 could fire 800 rounds per minute (involving ten magazine swaps per minute on each of the four guns). The weapons’ effective range was 2,406 yards (2,200m). The flatbed was disguised to look like an ordinary wooden freight wagon, the guns being raised up when brought into action against low-flying aircraft. Each Flakwagen had five crew compartments for the seventeen gunners. The officers and men were drawn from 9 Regiment General Göring, supplied to Hitler by the Luftwaffe chief.

Behind the Flakwagen was a baggage carriage, then the Führerwagen, Hitler’s personal Pullman carriage that contained a bedroom, bathroom, sitting room, valet’s quarters, and a conference room. Behind Hitler’s carriage was the Befehlswagen or Command Car, where Hitler’s staff officers worked. This carriage contained another conference room and a communications centre incorporating a 700-watt short wave radio transmitter. Next was the Begleitkommandowagen, a barracks on wheels for Hitler’s twenty-two-man SS-Begleit-Kommando and RSD detachment. Behind this was the dining carriage, two guest carriages, the Bodewagen or Bathing Car, another dining carriage, two sleeping cars for staff, then the Pressewagen or Press Car for Hitler’s press chief, Dr. Otto Dietrich, and his staff. Finally, another baggage carriage and another Flakwagen completed the train.

Using the Führersonderzug required several hours’ notice. The train was usually kept at Tempelhof maintenance depot and was shunted to the chosen departure station, usually taking two hours. Security concerns meant that the number of railway employees who knew the departure and arrival times, the route and any stops planned along the way was kept to an absolute minimum. One time, Hitler’s train pulled into a station and stopped beside a trainload of Jews who were being shipped off to a concentration camp. Whether he actually looked out of the window and saw this horrific sight is unknown. The blinds in his personal Pullman were usually kept lowered during the war.

The entire route that Hitler’s train would travel was patrolled – railway policemen would each be allotted a short ‘beat’ beside the track, this precaution making it almost impossible for anyone to plant a bomb on or beside the tracks to attempt to derail the train. Only collusion by the police would have made such an attempt feasible, which was an unlikely scenario.

At every station enroute where Hitler’s train was scheduled to stop the platform had to be kept completely clear of all luggage, packages or crates, anything that could conceal a bomb. Railway police guarded all entrances, exits, underpasses, bridges and stairways. Hitler’s RSD commander, Johann Rattenhuber, assumed command of all railway police for the duration of the train’s journey. Railway police also travelled aboard Hitler’s train, and one of their jobs was to carefully search every carriage for bombs and concealed weapons before a journey commenced. Technicians also travelled on board to rectify any faults that occurred during the journey. At the end of the journey all the written orders, timetables and documents that had been distributed to interested parties were gathered up, counted and then destroyed, to make sure that no one could plan a future attack on the same route.

One of the enduring images of Nazism is Hitler standing in the front of a large Mercedes-Benz limousine saluting as he is driven through dense throngs of adoring Germans. Hitler loved cars, took an interest in motor racing and enthusiastically supported the 1936 International Motor Show in Berlin. Hitler was the first world leader to use specially modified and armoured cars. The trend had begun in Prohibition America where gangsters like Al Capone paid huge sums to have their cars armoured and bullet proofed. As with everything to do with Hitler, security considerations revolutionized VIP transport, resulting in some truly monstrous machines.

The giant limousines were often Hitler’s first line of defence against lunatics and against more well organised assassination plots. Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s Hitler was repeatedly shot at whilst he was on the move, and providing properly armoured vehicles became paramount once Hitler became chancellor in 1933.

The Führer required serious cars, and the German carmaker Mercedes-Benz was more than happy to accommodate his wishes, particularly his interest in personal security. Hitler had first owned a red Benz in 1923 – it was this car that he had used to drive to the Burgerbraukeller in Munich shortly before launching his abortive putsch. During these tumultuous years Hitler was even involved in a car accident. ‘Rudolf Hess once told me that just before the seizure of power [in 1933], Hitler, Hess, Heinrich Hoffmann and Julius Schaub were all nearly killed in Hitler’s Mercedes due to an error made by a lorry driver,’ related Hitler’s valet, Heinz Linge. ‘Hitler was injured in the face and shoulder but with great composure calmed his co-passengers, still paralysed with shock, with the observation that Providence would not allow him to be killed since he still had a great mission to fulfil.’

Hitler stated in 1934 that he ‘did not tolerate a car manufactured by other companies in his escort and entourage,’ a ringing endorsement of what was now called Mercedes-Benz (though not something they like to highlight today). Between 1929 and 1942 Mercedes-Benz delivered a total of forty-four cars to the Reich Chancellery, the majority during the Nazi period.

Before 1935 Hitler used ordinary tourers and unarmoured limousines but his vulnerability to assassination caused a change in vehicle type. One incident in particular forced a change. After the marriage of Generalfeldmarschall Werner von Blomberg, Hitler drove to Kaiser Wilhelm II’s former mansion and hunting range on the Schorfheide to be with Göring. ‘Himmler drove ahead of us,’ recalled Hitler’s valet Linge. ‘Suddenly shots cracked out from the forest undergrowth. Himmler’s car stopped after being hit. Himmler, deeply shocked and pale, told Hitler that he had been shot at. Driving on after the incident, Hitler said: ‘That was certainly intended for me because Himmler does not usually drive ahead. It is also well known that I always sit at the side of the driver. The hits on Himmler’s car are in that area.’ Following this incident, Hitler took delivery of three specially modified Mercedes-Benz 540KW24 limousines, known with good reason as the “Swabian Colossus”.

Introduced at the 1936 Paris Motor Show, the 540K was one of the largest cars produced at the time. A total of twelve specially lengthened wheelbase cars were manufactured for use by the German government, huge six-seater convertible saloons. Hitler’s three personal 540K Paradewagens were kept in service until 1943. The Führer had had the vehicles ‘panzered’ or armoured with 4mm steel body armour, a 0.98 in (25mm) thick bulletproof windscreen and side windows and bulletproof tires. They weighed close to four tons each, reducing their top speed from 110 mph (177 kph) to just 87 mph (140 kph). They could withstand pistol and rifle fire and probably a bomb or grenade blast at close range. It was these cars that Hitler used to visit the Nuremberg rallies and one was even used to drive British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain up to the Berghof in 1938 during crisis meetings over the future of Czechoslovakia. Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler also utilised 540Ks, and many were kept at the New Reich Chancellery motor pool for the use of visiting VIPs and government ministers.

Hitler also used the 520G4W31 and 131 models. These equally huge vehicles had three axles and were used for cross-country driving and for military parades. Protection included a 1.18in (30mm) thick windscreen, 0.78in (20mm) thick roll-up windows, rear side windows armoured to 1.18in (30mm) and the back of the rear seat was reinforced by 0.31in (8mm) of steel plate. But the security features on the cars were only as good as the security protocols that governed the cars’ use. Hitler consistently toured around in armoured limousines with the top down. Although the side windows were rolled up, he was vulnerable to either a rifleman shooting from higher up (as in the case of John F. Kennedy in Dallas in 1963) or from a tossed grenade or bomb.

In 1942, following Reinhard Heydrich’s assassination in Prague, when British-trained Czech agents ambushed the Reich Protector, one throwing a grenade which exploded against the open-topped vehicle, the German government ordered another twenty 540Ks for the exclusive use of Nazi ministers and other leaders. Hitler’s protection, and that of his ministers and inner circle, became increasingly stringent as the war turned against Germany. Battlefield reverses left all of the Nazi leaders feeling increasingly vulnerable to assassination. In 1944 a final order for seventeen 540Ks was placed with Mercedes. The most famous 540K was probably “Blue Goose”, the car owned by Hermann Göring. Blue was the Reichsmarschall’s favourite colour and his personal 540K had Göring’s family crest on both rear doors.

From 1938 Hitler upgraded his collection of 540Ks with the addition of the Mercedes-Benz 770K150. Seven of these enormous vehicles were often used during the war years as Hitler’s personal transports. The chassis was twenty feet long and loaded down with 2,000-lbs (907kg) of armour plating and bulletproof glass. With fuel, oil and radiator fluid each 770K weighed almost 10,000-lbs (4,536kg). Side and floor armour consisted of 0.70in (18mm) of steel. The windows consisted of 1.575in (40mm) of armoured glass. Hitler allegedly tested the glass himself by firing a Luger pistol at it.

The 770K “Grosser Mercedes” was powered by a 230hp straight 8 with dual carburetors and dual ignition; superchargers would cut in automatically if the driver floored the accelerator. The armour reduced the vehicle’s top speed to about 100mph. Although fitted with fifty-one gallon fuel tanks, Hitler’s 770Ks made barely three miles to the gallon giving a range of only 150 miles (241 km). There was a compartment in the front dashboard and two more in the rear seats to hold pistols and an armoured plate could be raised behind the rear passenger seat. Hitler’s 770Ks were all painted midnight blue.

13 March 1943. An airfield set amongst dense forest just outside of the Ukrainian city of Smolensk. Hitler and his entourage walked towards two huge Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor aircraft belonging to the Führer transport squadron. A young army officer, Oberleutnant Fabian von Schlabrendorff, walked slightly behind the large party of senior officers headed for Hitler’s plane, carrying a medium-sized wooden box in his arms. As the Führer climbed a short ladder into the Condor, followed by his senior staff members, Generalmajor Henning von Treskow reminded Oberstleutnant Heinz Brandt, who would be travelling with the Führer, to take the parcel. Unnoticed, Schlabrendorff had opened the top, crushed a short metal tube with a pair of pliars, resealed the package and then stepped forward smartly and handed it to Brandt. Inside are what appeared at first glance to be two bottles of French cognac. Treskow inveigled Brandt into taking the liquor to Germany for him as payment for a bet lost to Generalmajor Helmut Stieff, Chief of Organisation at Army High Command. Brandt was more than happy to oblige and such behaviour was not unusual among the senior military officers who worked around the Führer.

As the two Condors powered down the grass landing strip and headed off into the wide blue sky towards Germany Treskow and Schlabrendorff exchanged a knowing look. In thirty minutes Hitler would be dead and the plan to take back Germany from the Nazis would swing into action.

Due to the size of Hitler’s empire, the most efficient way to get around it was by plane. As with so many aspects of Hitler’s leadership style and security arrangements, he set a standard by using aeroplanes in an era when air travel was still a novelty. Hitler was the first modern politician to regularly use an aircraft, beginning during his election campaigning in the 1920s and 1930s. Once he became a war leader he utilised a fleet of aircraft to move speedily between his various headquarters, much like modern presidents and generals today. The speed of the modern battlefield dictated that if he wished to exercise effective command and control, and Hitler became increasingly ‘hands on’ as the war progressed much to his generals’ indignation and frustration, then air travel was really the only way that he could do this. But air travel is intrinsically dangerous, particularly during wartime, so extreme precautions were taken by the Germans to ensure that Hitler travelled not only in comfort, but also in safety, including some very novel emergency equipment designed to preserve the Fuhrer’s life if his aircraft was ever fatally damaged.

Hitler first flew to a war front during the Polish campaign in September 1939. Two modified Junkers Ju 52/3m transport planes, the tri-motor corrugated metal workhorses of the German armed forces, were used to fly Hitler and his military entourage to a recently captured Polish airfield closely escorted by several Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter planes. Following a short meeting at an army headquarters at the front Hitler was flown back to Berlin by his personal pilot and friend, Hans Baur.

Baur, who was born in Ampfing, Bavaria in 1897, had transferred to the flying service in 1915 as an artillery spotter. By 1918 he claimed six aerial victories, plus three probables, and had been awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class for bravery. After the war Baur worked as a courier pilot and was one of the first six pilots employed by the fledging German national carrier Lufthansa. In 1926 he pioneered Lufthansa’s new ‘Alpine Route’ between Munich, Milan and Rome, one of his passengers being Tsar Boris III of Bulgaria. That same year Baur joined the Nazi Party and later came to Hitler’s attention. He first flew Hitler during the 1932 elections. When Hitler became chancellor in 1933 he acquired a Junkers Ju 52/3m that he named ‘Immelmann II’ in honour of a famous First World War German fighter ace. Baur was selected to be the Führer’s principal pilot. At this time because of the stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles, the Luftwaffe did not exist, so in order to give Baur some authority and power Hitler had him appointed an SS-Standartenführer. Because of this, Hitler’s personal pilots were never Luftwaffe officers, always SS.

After the old Reich President Paul von Hindenburg died in 1934 Hitler was able to absorb the posts of president and chancellor into one new office, becoming ‘Führer’. He also reorganized the government and, with Lufthansa help, acquired a further Ju 52/3m, which he christened ‘Richthofen’ after the Red Baron. In 1935 ‘Immelmann II’ was replaced by ‘Buddecke’ and ‘Richthofen’ was renamed ‘Immelmann II’. Hitler used his new powers to create the Regirungsstaffel (Government Squadron) with Baur as its commander headquartered at Berlin’s vast Tempelhof Airport.

The new Government Squadron was quickly expanded to included eight Ju 52/3ms, each capable of carrying seventeen passengers in relative comfort. These aircraft were to be used to ferry around Hitler, his senior inner circle of ministers and the all-important army generals. Some leaders were of such importance that they were assigned their own personal pilots, all of the flyers being former Lufthansa captains. Baur’s second-in-command and co-pilot on Hitler’s aircraft was Georg Betz. Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess was assigned Kurt Schuhmann. Propaganda Minister Dr. Goebbels’ pilot was Max von Muller, while Grossadmiral Erich Raeder, professional head of the German Navy, was assigned Peter Strasser. An aristocrat, Count Schilly, flew the two chiefs of the army general staff, Werner Frengel and Walther von Brauchitsch.

Baur soon became one of Hitler’s court favourites. Hitler knew how to extract personal loyalty from his immediate subordinates and Baur was no exception. To celebrate Baur’s 40th birthday in 1937 Hitler hosted a lavish dinner in his honour at the New Reich Chancellery in Berlin. He also presented him with a brand new Mercedes car as a present. It is small wonder that so many of Hitler’s subordinates stayed close to the Führer until the regime’s very bitter end.

In September 1939 Hitler ordered the government squadron renamed. It would now be called Die Fliegerstaffel des Führers (F.d.F), becoming in effect Hitler’s private squadron.

On 5 October 1939 Hitler first flew in the aircraft that was to become his primary means of aerial transport during the war – the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor. Baur had convinced Hitler that the Condor was a superior aircraft over the older Ju 52, as well as being much safer. Hitler, who often consulted Baur on matters aerial, including Luftwaffe strategy, was easily won over by his trusted subordinate. Originally proposed to Lufthansa as a transatlantic airliner by Kurt Tank of Focke-Wulf, the aircraft entered service in 1937. In Luftwaffe service the Condor, named for the famous Andean bird because of its huge wingspan, was utilized as a transport, maritime reconnaissance aircraft and bomber. In the transport configuration a Condor could carry thirty full-armed troops. With a length of 76ft 11in (23.45m) and a wingspan of 107ft 9in (32.85m), the Condor had a maximum speed of 224mph (360km/h) at 15,750ft (4,800m) with a service ceiling of 19,700ft (6,000m). The aircraft’s range was an impressive 2,212 miles (3,560km).

As well as Hitler, some of the Reich’s more important military commanders were assigned personal aircraft, but not at this stage the new Condor. These aircraft were mostly converted Heinkel He 111, Junkers Ju 52/3m, Siebel Fh 104A or the small Fieseler Fi 156 Storch spotter plane.

In Berlin on 10 November 1939 Hitler flew for the first time in his new personal transport aircraft – an Fw 200A-0 named ‘Immelmann III’, taking off from Templehof Airport. The day before Hitler had narrowly avoided being killed by a bomb planted by a carpenter called Georg Elser inside the Burgerbraukeller beer hall in Munich.

By 1942 Baur had requested three armed Condor aircraft for the F.d.F. At the Wolfs Lair at Rastenburg, Hitler’s main Eastern Front HQ, the runway had been strengthened and also lengthened to accommodate these larger aircraft. The first aircraft delivered was an Fw 200C-3/U9 marked KE+IX. This plane was not intended as the Führer’s personal transport – instead it would act as a passenger plane for ferrying around Hitler’s large retinue of staff when visiting the front. It was armed with a 0.5 in (13mm) MG131 machine gun in an upper turret just behind the cockpit and a 0.3 in (7.9mm) MG15 firing from a raised dorsal position aft of the main door. Another MG15 was mounted in the nose. Under its fuselage was a long gondola with a machine gun position. The other two aircraft were also delivered at this point. Of course, these weapons would be a last resort for it was never expected that F.d.F. should have to fight it out with enemy fighters. When they were airborne these large transports were well protected by a strong Luftwaffe fighter escort.

Hitler’s personal plane, the “Führermachine”, was an Fw 200C-4/U1 (CE+IB). It had the same comfortable layout as the older ‘Immelmann III’. Behind the cockpit was an equipment compartment containing the flight engineer’s panel and positions for the radio operator and navigator. From here two of the gun positions could also be accessed. The next small compartment housed equipment, lubricants and fuel tanks, with a small toilet on the starboard side. Behind this, accessed through a door, was Hitler’s specially insulated cabin containing an elaborate ‘parachute seat’ on the right facing forward, with a wooden table in front.

According to Baur the Führer’s seat was fitted with a parachute harness. This harness was installed in the back of the seat cushions. The backrest was attached above by two buttons in the chair, and this had to be pulled forward to reach the stowed parachute. In an emergency Hitler would have donned the parachute harness in the back of the seat and pulled hard on a red lever on the wall. This would have opened a spring loaded escape hatch in the floor of the aircraft in front of him. The seat back cushion and seat bottom cushion remained attached to the jumper with the parachute harness. Hitler would then had climbed through the hatch and baled out. Once free of the aircraft he would have manually released his parachute and floated down to safety. However, the likelihood of a middle aged and increasingly infirm man managing this in an emergency does seem a little far-fetched. Normal parachutes were stored in the cabin for Hitler’s other passengers who would have presumably baled out through the main door or through one of the gun positions. Needless to say, none of this was ever put to the test in reality, though a Luftwaffe volunteer made a successful test of Hitler’s parachute seat, proving the theory at least. All parachutes were checked at least once a month.

On the left side of the cabin were four seats, two side by side. The cabin was armoured against enemy machine gun bullets, cannon shells and anti-aircraft bursts. The walls, floor and ceiling were lined with 0.47 in (12mm) thick armour plate and the windows were 1.96 in (50mm) thick bulletproof glass.

The crew consisted of pilot Baur, co-pilot Betz, a flight engineer (who also doubled as a gunner), navigator/radio operator (also working as a gunner if required), and a steward. Moving aft beyond Hitler’s cabin was another passenger cabin that was fitted with six seats, two on the right facing each other, and four on the left that also faced one another. Maximum passenger capacity on Hitler’s personal aircraft was thirteen.

In both cabins the windows had curtains for privacy and to prevent sun glare and the interior was finished in highly polished wood so that it more closely resembled a railway carriage or a ship’s cabin than an aircraft. ‘The inside of Hitler’s Condor looked like a gent’s salon,’ recalled Hauptmann Alexander Stahlberg, who flew in the aircraft in his capacity as an aide to Generaloberst Erich von Manstein in mid-April 1942 from his headquarters in the Crimea to a meeting at the Wolf’s Lair. ‘The walls were wood-panelled and the furniture leather covered. China and cutlery were solid silver and bore the NSDAP insignia. A steward was on board and served meals and drinks as desired.’

At the rear of the plane was a small galley, located behind the rear gunner’s position. No cooking was permitted on Hitler’s plane; instead a specially insulated cabinet contained pre-heated meals that were similar to those found on today’s commercial airliners. Hot coffee and hot water for tea were also available, though not alcohol. Luggage and clothing was stored separately in an unheated cargo hold and for safety each passenger had an oxygen tank under his seat.

The third Condor acquired by Baur for the F.d.F. was an Fw 200C-4/U2 (CE+IC). This plane was used primarily for transporting staff and guests but Hitler did travel on this and KE+IX occasionally. CE+IC was fitted with fourteen seats in a single large panelled cabin, but lacked a special parachute seat for the Führer.

Because of the added weight caused by bulletproof windows and armour plating CE+IB and CE+IC had a maximum ceiling of 19,030 feet (5,800m), a top speed of 205 mph (330 kph) (though they cruised at 174 mph (280 kph)) and normally loaded could travel just over 2,000 miles (3,219km) without refuelling.

Before every trip that carried the Führer was very carefully managed. In particular, measures were taken to prevent the use of bombs onboard the plane. The best type of bomb to be successfully smuggled aboard Hitler’s plane would have been one fitted with a barometric fuse that detonated when the plane reached a certain altitude. This avoided the need for ticking parts in the bomb. To counter anyone trying something like this before every trip Hitler’s aircraft was taken for a ten or fifteen minute test flight, including up to cruising altitude. Of course, such measures were useless had anyone managed to smuggle a time bomb aboard Hitler’s plane.

The Condor also had a significant Achilles heel, a design fault that could have killed Hitler on several occasions. In June 1942 when his Condor landed at Michaeli near Wiborg in Finland so that Hitler could have a meeting with Finnish leader Field Marshal Mannerheim, Finnish ground crewmen were filmed running towards the plane’s landing gear armed with fire extinguishers. The problem was in the design of the brake actuating cams. When the brakes were used ‘forcefully’, such as in landing, they overcentred and locked over-so slightly in the ‘on’ position, with the brake shoes dragging on the drums. This friction would cause the linings to catch fire on landing. The problem could also manifest itself during take off as well. If the plane was parked overnight with the brakes on, or if the brakes had not released cleanly on parking, they did not free up fully when taxiing and this would lead to the linings catching fire on take off. This could be lethal, and several Condors were lost in Luftwaffe service because of this small technical fault. The wheels retracted into bays that were adjacent to the wing fuel tanks, the last place one would want to have a fire.

Air travel was dangerous, particularly during wartime, yet Hitler seemed to prefer the risks rather than using his train for most long-distance journeys. Hundreds of even thousands of railway workers, any one of whom could have been a potential assassin, would know about Hitler’s train and its route, whereas air travel and Hitler’s unpredictable changes in his plans, better protected the Führer from plotters. But in flying he risked thunderstorms, burning wheels, foggy takeoffs and landings, soft ground, and later in the war enemy fighters and flak.

The 13 March 1943 should have been Hitler’s last day alive. Oberst Brandt handed the parcel to the plane’s steward, who placed it with the other luggage in the unheated cargo hold. This was in direct contravention of the accepted rules for loading Hitler’s aircraft. All servicing, repairs and loading of luggage at any airport only could be done in the presence of the flight engineer or another member of the crew, as well as in the presence of RSD guards. Brandt knew this full-well, but as with many security procedures the people most likely to break them were those who lived within this restrictive arena day in, day out. Perhaps it was a case of familiarity breeding contempt.

As the two Condor’s taxied down the grass strip and lifted off into the clear blue sky Treskow and Schlabrendorff exchanged a look before settling into a radio truck to listen for news of the Fuhrer’s demise. In thirty minutes, with Hitler dead, they would institute a takeover plan. General der Infanterie Friedrich Olbricht in Berlin would order the Replacement Army to seize the capital as well as Vienna and Munich.

At the airfield outside Smolensk the expected news that Hitler’s plane had crashed did not arrive. Something had gone terribly awry. ‘Treskow and I,’ wrote Oberleutnant von Schlabrendorff, ‘judging from our own experiments, were convinced that the amount of explosive in the bomb would be sufficient to tear the entire plane apart, or at least to make a fatal crash inevitable.’ No word came for two agonizing hours. The two men could not understand what had happened – the plan and the equipment appeared to be foolproof.

Generalmajor Treskow was suddenly informed by phone that the Führer’s plane had landed safely at Rastenburg airfield. It was almost unbelievable. Schlabrendorff hurriedly took the next plane to Germany and retrieved the parcel before Brandt became aware of its true contents. When the bomb was examined it was found that it had actually worked perfectly. The acid had released the spring hammer and struck the percussion cap. But because of the intense cold inside the unheated cargo hold, the percussion cap had failed to detonate and the bomb had not exploded. Hitler had been saved from certain death once again by the tiniest of flaws, one conspirator commenting bitterly that he appeared to have a ‘guardian devil.’ If the parcel had been carried inside the heated passenger cabin everyone onboard the plane would have perished. The explosives were returned to storage until they could be used for another attempt to kill Hitler. That attempt would come on 20 July 1944.