‘Am Under Heavy Fire’

‘Suddenly we saw a line of splashes rip across the water just astern of us, followed by an inoffensive pop, pop, pop, popping noise. Bater gasped “I’m scared P.O.” and doing my best not to look scared said, “That makes two of us.’

On the open bridge of the sloop HMS Amethyst, Lieutenant-Commander Bernard Skinner raised his binoculars and searched the banks of the wide Yangtze River, his Chinese river pilot calling out small course corrections to avoid the many sandbars and navigation hazards. Skinner’s other officers also scanned the banks, all looking for the origin of the artillery shells that tore overhead with a whine or threw up great geysers of water close to the ship.

The Amethyst was on her way to Nanking from Shanghai, wending her way along China’s greatest river as her predecessors had been doing for over a hundred years. It was April 1949 and China was in the grip of a horrific civil war. Britain’s position in the Middle Kingdom was extremely unsteady.

Skinner turned to his second-in-command: “No. 1, action stations.’ The young lieutenant quickly relayed the command, the ship’s electric warning bell ringing insistently as all hands ran to their assigned posts, the gunners dragging on white anti-flash hoods and gauntlets as they manned the turrets forward and aft.

‘No. 1, get the Union Jacks unfurled, starboard first.’ The crew quickly unfurled huge British flags on both sides of the ship, clearly marking the vessel as neutral. ‘Full ahead both’, ordered Skinner down the voice pipe to the wheelhouse beneath the bridge, the coxswain repeating his order. The Amethyst picked up speed, but still the shells kept coming. ‘Yeoman, break out battle ensign,’ ordered Skinner, and atop the radar tower the White Ensign proudly snapped out into the wind. ‘Its coming from the north bank, sir,’ said No. 1, as they all trained their binoculars onto the Communist-held side of the river. ‘I saw the flash that time.’

Skinner did not hesitate. ‘Tell Director, train on bearing Green 70.’ The gunnery officer ordered the turrets to turn onto the north bank, and the guns were loaded. The gunnery officer could not yet see the enemy guns, and could only estimate their position and range whilst he looked for their smoke.

‘Open fire!’ said Skinner. A moment later the Amethyst’s 4-inch guns started pumping shells into the riverbank, as Chinese shells started to get the range and began to batter the British ship mercilessly. ‘Tell Wireless Office – make from Amethyst to all ships: ‘Am under heavy fire’. Seconds later a Chinese shell struck the bridge, killing or wounding everyone. Britain was fighting its last battle in China.

The Western domination of China formally came to an end in 1943 when the governments of the Allied powers agreed to relinquish control over their many concessions and enclaves. With the exception of Hong Kong, a crown colony, all other British concessions were signed over to Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists. Any future trading with China would be conducted under Chinese laws, foreigners losing their rights to extraterritoriality. Of course, this was all rather a moot point as the concessions were then all under Japanese occupation. It was only in September 1945, following the Japanese surrender, that British armed forces returned to a very changed China.

Postwar China was in turmoil. The uneasy truce that had largely held between Chiang’s Nationalists and Mao Zedong’s Communists had completely broken down once the common Japanese enemy had been removed from the picture. A civil war based on a conflict between two political ideologies had swiftly broken out, a disaster not just for war ravaged China, but also for Western hopes of re-establishing lucrative trade now that the Japanese were gone. The situation was complicated because the Nationalist capital, then recognised as the legitimate government of China, was located in Nanking, far up the Yangtze River from the coast, and British traders and diplomats were isolated and increasingly vulnerable as Communist forces approached the city. In order to protect British interests in Nanking, the Royal Navy stationed a guard ship there with orders to evacuate British and Commonwealth nationals if the Communists threatened the city. The days of the China gunboat were over, these useful vessels having become casualties during the war or handed over to the Nationalists as bribes to keep them on the Allied side. But the Yangtze is a huge river, easily navigable for large ships for hundreds of miles into the Chinese interior.

In April 1949 the guard ship at Nanking was HMS Consort, a 1,885-ton C-class destroyer built in 1944. With a full complement of 186, including embarked Royal Marines, the Consort was due to be relieved by another ship coming up from Shanghai, HMS Amethyst. The Amethyst was a smaller vessel than the Consort, officially designated a Modified Black Swan-class sloop of 1,350-tons, though with a larger crew numbering 192 men under skipper Bernard Skinner. A sloop was a large corvette designed primarily as a convoy escort and anti-aircraft vessel. Built in Scotland in 1942, the Amethyst had scored some successes as an anti U-boat patrol vessel during the war. She was armed with six quick-firing Mk. XVI 4-inch anti-aircraft and duel purpose guns housed in three twin turrets, two fore, and one aft. These guns fired 35lb high explosive shells and the vessel was also armed with heavy machine guns.

No one on board the Amethyst expected a fight – her mission was routine, though the crew expected to see some fighting between Nationalist and Communist troops for Mao’s forces had reached the north bank of the Yangtze River and dug in while more troops moved on Nanking. It was only a matter of time before the Communists crossed the river and the Amethyst would be called upon to evacuate British and Commonwealth citizens from the Chinese capital. The British certainly underestimated the degree of ingrained hostility towards them harboured by Communist troops who looked upon the British and other foreigners as having abused, robbed and cheated China for over a hundred years for their own profit and power. The Communists did not want to see ‘imperialist’ ships on the Yangtze.

In Nanking, the Consort was tied up to pontoons secured to the riverbank adjacent to a dried egg powder factory. ‘If, or when civil disorder occurred, all British nationals were told to make for the dried egg powder factory where Jolly Jack would defend them by turning the egg factory into a kind of fort; armed with Lanchesters, Bren guns, rifles and pistols, with Consort on its river flank with its heavier arms,’ recalled Petty Officer Terry Currie, who was serving on the Consort at the time. ‘Every day large junks passed Consort jam-packed with what I took to be refugees. They all looked very poor and dirty in their padded quilted jackets.’

Ordinary British sailors understood little of the situation in China, and perhaps cared even less. ‘Civil war was raging in China at this time,’ recalled Currie, ‘yet I cannot recall being unduly worried – was their war – nothing to do with us. Such was the effect of my cocooned and controlled life [aboard ship] I thought that Mao’s Army was a rabble of peasants armed with pitchforks and staves.’

On 20 April, HMS Amethyst was making her way up the Yangtze when, at 8.31am, a burst of small arms fire from the north bank passed close to the ship. Ten shells in quick succession followed this from a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) artillery battery, the shells all dropping well short of the Amethyst, throwing up great plumes of muddy river water. Skinner was not alarmed – he assumed that the Communists were firing at the Nationalist bank of the river and had misjudged their fall of shot. Skinner ordered speed to be increased and two very large Union Jacks to be unfurled on both sides of the ship to make sure that those ashore knew her nationality and neutral status. The firing stopped immediately.

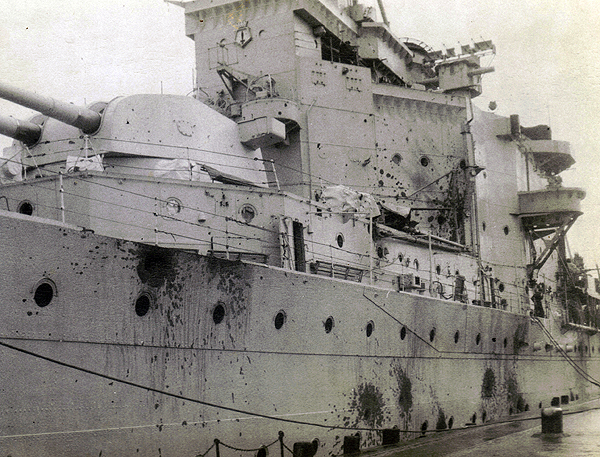

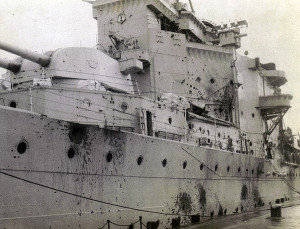

At 9.30am the Amethyst was passing the town of Kiangyin (now Jiangyin), approximately 100 miles east of Nanking by river. The boom of artillery startled the crew as PLA batteries on Low Island opened fire. This time there was no doubt that the gunners’ target was the British ship. The first shell tore over the Amethyst with a whine and exploded in the river. The crew was at action stations. The second shell struck the wheelhouse, causing extensive damage and mortally wounding Commander Skinner and injuring his first lieutenant, Geoffrey Weston. The coxswain was also wounded, but he clung on to the ship’s wheel. During the following few minutes the Amethyst was repeatedly struck by PLA shells. One tore through the sick bay and the port engine room, reducing the ship’s power. The injured coxswain grounded the Amethyst on Rose Island, the vessel coming to rest in a manner that prevented her two forward turrets from engaging the shore battery. PLA shells slammed into the stationary ship, killing and wounding dozens. Lieutenant Weston managed to send a frantic radio message to all nearby vessels: ‘Under heavy fire. Am aground in approx position 31.10′ North 119.50′ East. Large number of casualties.’ A shell struck the radio room, knocking out the ship’s communications, while another smashed the generator, disabling the vessel’s electrics, including power to the gun turrets. The Amethyst was helpless and stuck fast.

On the quarterdeck the ship’s doctor, Surgeon-Lieutenant John Alderton, ran out to try and tend to the many wounded accompanied by Sick Berth Attendant Owen Aubrey. A Chinese shell instantly killed both men.

Although the two forward turrets could not be brought to bear on the enemy, the aft turret managed to fire thirty rounds before a Chinese shell hit home, disabling one of the two barrels. The other barrel fired off a few more shells until the wounded Lieutenant Weston, who had assumed command from the dying Skinner, ordered it to ceasefire in the hope that this would encourage the Chinese to do likewise. Weston now ordered as many of the crew as possible over the side. As shells continued to hammer the stricken Amethyst everyone who could swam to Rose Island, all the time under a fearsome barrage of artillery shells and machine gun bullets. Several were killed. The walking wounded and non-swimmers managed to get away in the only ship’s boat that was still undamaged.

A total of fifty-nine ratings and four Chinese mess boys made it alive to the Nationalist-controlled south bank. They were taken to a Nationalist Army field hospital for treatment before being trucked back to Shanghai. Forty unwounded sailors remained aboard, along with twelve wounded and fifteen dead. Weston ordered the unwounded to arm themselves with Lee Enfield rifles and Bren light machine guns and to prepare to repel boarders.

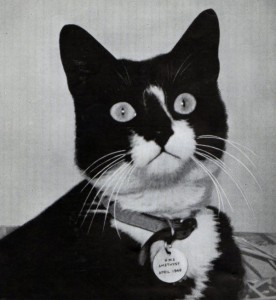

One member of the crew who was not evacuated was Simon, the ship’s cat. In March 1948, when the Amethyst had been moored in Hong Kong, Ordinary Seaman George Hickinbottom had befriended the young stray that was hanging around the docks. The seventeen-year-old Hickinbottom had smuggled Simon aboard ship and before long the crew, who appreciated Simon’s ratting expeditions below decks, had adopted the friendly cat. Simon would leave dead rats a presents in sailors’ bunks and had taken to sleeping in skipper Commander Ian Griffiths cap inside his cabin. Simon was considered lucky mascot and when Bernard Skinner took over command in late 1948 he soon took a liking to the affable feline.

On 21 April 1949 Simon was in Skinner’s cabin when it took a direct hit from a Chinese shell. As the evacuation of the crew was underway a badly wounded Simon crawled out onto the deck where sailors immediately took him to the sick bay for treatment. Four pieces of shrapnel were removed from the cat and it did not look as though the plucky animal would survive.

By 11.00am the Communist shelling had stopped, but any movement on the battered British ship attracted deadly accurate Chinese snipers. A total of twenty-two British sailors had been killed and another thirty-one wounded. On the following day Bernard Skinner, their mortally wounded skipper, also died.

Aboard the Consort, quietly anchored in Nanking, the morning routine was about to be rudely shattered. ‘I noticed Hutch, the Petty Officer Yeoman of Signals approaching the Captain with his signal board in his hand,’ recalled Petty Officer Currie. ‘He saluted the Captain, who returned his salute and then he read his signal. The Captain turned and…hurriedly made for the gangway. We were told that HMS Amethyst had come under fire. She was aground, and had suffered casualties.’

‘In no time all lines were let go and the ship swung around to head down stream at thirty knots, the fastest a British warship had ever travelled on the Yangtze at that time.’ In order to make her neutral status abundantly clear to the Chinese, special precautions had been taken. ‘We had two white sheets, flags of truce – flying from both yardarms,’ recalled Currie. ‘On either side of the bridge large canvas squares were lashed upon which were painted Union Flags. Our white ensign streamed rippling from our stern.’

The Consort intended to take the battered Amethyst in tow and aboard the Amethyst towing cables were hastily prepared. Unfortunately, the entire plan was doomed to failure as the Consort immediately attracted considerable fire from the north bank. Currie and Able Seaman Bater were standing by the unmanned “Y” gun shield, the Consort having a reduced peacetime complement that meant that some guns were missing crews. ‘Suddenly we saw a line of splashes rip across the water just astern of us, followed by an inoffensive pop, pop, pop, popping noise,’ wrote Currie. ‘Bater gasped “I’m scared P.O.” and doing my best not to look scared said, “That makes two of us.’” Bater was called forward and Currie requested a Bren gun and ammunition, which was granted. ‘By now the three 4.5” guns had opened up, also I could hear the twin Bofors thumping away – all hell had broken loose.’

The Consort steamed past the Amethyst, preparing to take her under tow. ‘The river at this point was about one third of a mile wide, ideal for a crossing,’ said Currie. ‘I could see one of their sandbagged gun positions and when they fired, three or four guns together, the blast from the guns lifted the dust in an arc in front of the position.’ Currie lay in the prone position on the deck and loaded his Bren gun. ‘I put my sights on 300 yards and as taught squeezed off a short burst and saw my fall of shot hit the water just in front of the sandbags. I raised the sight to 350 yards and squeezed off another burst (I had no tracers), no hits on the water so I was either hitting the sandbags or at least worrying the Chinese gunner.’

The Consort turned about and made another pass, firing as she went but was unable to stop and take the Amethyst in tow. ‘Our 4.5” shells were exploding on the banks of the river, the shells from the gun batteries were screaming overhead or hitting the water, some exploding and scattering shrapnel across the surface,’ recalled Currie. ‘I could see a gun battery fire and instantaneously the shells either hit or roared overhead.’ The Consort took an almighty battering as she was fired on at virtually point blank range on the river. ‘I decided to go for’rd and as I reached the starboard door at the break of the foc’sle I saw young Able Seaman Bater, he looked shocked and was plastered with, what looked like, mince. I asked if he was ok. He made a shaky gesture with his thumb “I’m ok – it’s from them in there.”’ The horrific nature of the fighting soon revealed itself to Currie. ‘I stepped over the dwarf bulkhead slotted into the bottom of the door and I looked down. An electrician lay dead, his lower jaw shot away, the dirty water from a shattered fire main ran across Consort’s slightly rolling deck and covered his face and body. A stoker lay dead, there was a hole in his side; his liver gleamed wetly on an ammunition box. On the portside lay a messmate, the P.O Telegraphist, disembowelled and one leg off, hit by two 75mm shells – I made my way to the bridge; it was at this time that I think action had been broken off.’

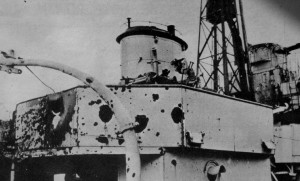

Currie was among many veterans of this battle who later questioned the common sense of placing British warships in such a dangerous situation. ‘While Consort was making a turn, and was virtually a stopped target in the river, the Chinese gunners, in military terms “boxed us.” They put a hole in the barrel of “A” gun and killed an ordinary seaman. “B” gun received a hit removing the gun trainer’s seat and taking most of his backside with it. He died later.’ The Consort narrowly avoided the same fate as the Amethyst. ‘The wheelhouse was hit killing the C.P.O Coxswain and Consort raced for the bank out of control – the Captain steered her by using the twin screws,’ wrote Currie. ‘The gun transmitting station was hit killing the petty officer and a young A.B. The radio office was also hit. Many 37mm solid anti tank shells passed right through the ship wounding many sailors.’

The Consort gave up and signalled the Amethyst that she was heading for Shanghai. The destroyer had taken fifty-six hits from shells, with ten crew killed and thirty wounded.

The Amethyst remained stuck fast. Any movement on the ship’s superstructure attracted Chinese sniper fire, but the Communists had at least stopped shelling the vessel. It seemed clear that the Chinese did not wish to sink the British warship as they could have pounded her to pieces with impunity, but instead the Amethyst was being held hostage. But the Chinese had underestimated both Lieutenant Weston’s resourcefulness and the determination of the Admiralty to rescue the Amethyst. For several days, Weston had tried to free the Amethyst from the sand bank until, on the night of the 22nd, he finally managed it after pumping twenty tons of oil fuel aft had lightened the vessel. Earlier in the afternoon, Weston had received a heartening signal from China Station HQ: ‘HM Ships London and Black Swan are moving up river to escort the Amethyst down stream. Be ready to move.’

The Consort, instead of heading directly for Shanghai, had instead rendezvoused with HMS London, a 9,750-ton County-class heavy cruiser dating from 1927. During the war she had been part of the task force that had hunted and destroyed the German battleship Bismarck as well undertaking the hazardous task of escorting convoys to Murmansk in northern Russia. Armed with 8-inch guns capable of delivering a 256lb high explosive shell up to fifteen miles away, she was the most formidable vessel on the Yangtze in 1949. The Black Swan was Amethyst’s sister ship, built in 1939. She had been the first British ship into Shanghai in September 1945 in company with the cruiser HMS Belfast, following the Japanese surrender.

When the captain of the Consort heard that the London and Black Swan were going to try and reach the Amethyst, he volunteered his battered vessel. ‘As we were so badly damaged in areas vital to our fighting ability he was ordered to return to Shanghai by the commanding officer of London,’ wrote Petty Officer Currie. ‘This we did and on our arrival, ambulances were waiting on the jetty to take our wounded to hospital. We carried our dead shipmates ashore on stretchers. They had been sewn up in canvas and each body was wrapped in a white ensign. As we carried our dead, a group of American sailors who had collected on the jetty, formed a sort of impromptu mourning party by dividing into two ragged ranks and then saluting as we filed past them to awaiting trucks. This gesture was more respectful than the headline in Time Magazine a few weeks later “Limey’s kicked out of Chinese River.” Who needed enemies when you have friends like?’

HMS London and Black Swan were greeted by a storm of fire. The Chinese were not intimidated by the large British cruiser and liberally plastered her and the Black Swan with both high explosive and anti-tank shells from batteries near Bate Point. The London was holed twelve times on her port side, her two forward 8-inch turrets and “X” after turret were damaged and rendered inoperable, and her bridge was hit several times. The London suffered fifteen killed and thirty wounded while the Black Swan’s superstructure was severely damaged, twelve men being wounded. Reluctantly, the order was given to withdraw down the river lest the London and Black Swan end up in a similar condition to the Amethyst.

This action revealed the limitations of using large warships as gunboats on a river against an enemy well armed with modern artillery. The London, for all of her size and armament, just ended up as a large target for the Chinese. Because of the narrowness of the river she was unable to stay out of range of the Chinese guns while hitting them with impunity with her big 8-inch main armament. The much smaller prewar Yangtze River gunboats had never had to face such a well armed and determined opponent as the PLA proved to be.

Captain Cazaler of the London, in his Captain’s Report of the action, noted that the vessel had fired 132 8-inch shells, as well as 449 4-inch and over 2,000 light anti-aircraft shells during the brief but very violent river battle. ‘All damage to the ship was quickly and efficiently dealt with by the Damage Control Parties,’ wrote Cazaler, ‘whose performance I consider to be outstanding, taking into consideration the difficulty of providing realistic training in these duties. The bearing and conduct of the Ship’s Company, a large proportion of whom are very young and were experiencing action for the first time, was beyond praise.’ Cazaler singled out the gun crews for particular praise. ‘As an instance, the 4in Gun Crews and Supply Parties suffered 38% casualties, who were not replaced as they fell.’

Later on the 22nd a RAF Sunderland flying boat flew up from Hong Kong carrying Flight Lieutenant Michael Fearnley, an air force doctor, and some urgently needed medical supplies. The huge white aircraft landed in the river near to the Amethyst and quickly off-loaded the doctor and supplies just as the PLA opened fire. Shells landed as close as 100 yards away from the Sunderland and the pilot could not linger. A boat also arrived from Nanking carrying Lieutenant-Commander John Kerans, the British Embassy’s Assistant Naval Attaché, who had been ordered to assume command of the Amethyst.

Some members of the crew later returned to the Amethyst on the 22 April. Vice-Admiral A.C.G. Madden, Commander-in-Chief Far East Station reported to the Admiralty that the vessel had three Royal Navy officers, an RAF doctor, fifty-two ratings and eight Chinese mess attendants embarked. Madden sent a message to the Amethyst: ‘In a splendid performance by all on board ship the work of your sole telegraphist evokes my admiration. I cannot be grateful enough to him for his help.’ Madden was also busy organising assistance for the wounded crew members who were arriving in Shanghai overland. The American hospital ship USS Repose arrived off Woosung and offered her assistance, which Madden gratefully accepted.

In the meantime, the strategic situation in Eastern China had changed dramatically, making the Amethyst’s rescue even more perilous an undertaking. On the same day that HMS London and Black Swan attempted to rescue the Amethyst, the Communists had launched a general offensive along a 250-mile front. One column penetrated as close as forty-five miles from Shanghai. Nationalist forces evacuated the town of Chinkiang and the Shanghai–Nanking Railway was cut. Kiangyin Navy Base, eighty-five miles below Nanking on the Yangtze River, went over to the Communists. Another column threatened the city of Wuxi, seventy miles from Shanghai.

By the 23rd the battered Amethyst was anchored close to Chinkiang. In Shanghai, a memorial service was held at Holy Trinity Cathedral for the twenty-three dead sailors who had been sent by train and the British Resident’s Association started a relief fund to raise money for the dead men’s dependents.

On 26 April, the Communists occupied Nanking. There was no resistance as the Nationalist 28th Army had already evacuated the city along with its positions on the Yangtze River. It had joined up with the 45th Army and the 100,000 soldiers had begun to march towards Hangchow (now Hangzhou) near Shanghai. Widespread civilian looting had broken out in the Chinese capital. ‘While the looters were at work,’ reported a British newspaper, ‘military demolition squads were blowing up Hsiakwan railway station and setting fire to ammunition dumps, aircraft and aviation fuel, lorries, jeeps, stores of weapons, and river craft.’ Order had completely broken down. ‘Policemen stripped off their uniforms and disappeared from the streets.’ Former general Ma Qing Yuan contacted the Communists and arranged for them to enter once his men had brought the looting under control, and he eventually imposed some semblance of order. Over 900,000 Communist troops had crossed the Yangtze in several places, and the Amethyst was now deep inside hostile territory.

The Communist media had begun to report on the Amethyst situation, though for propaganda purposes its reportage was extremely distorted and inaccurate. ‘On Wednesday “two enemy war vessels” suddenly opened fire on Communist positions on the north bank,’ ran one report. ‘The Communists…returned fire and hit one of the vessels [Amethyst], which subsequently sunk, while the other [Consort] steamed to the West and was “half sunk” near Chinkiang. Then another enemy war vessel [London], steaming east from Chinkiang, reached the spot and opened fire.’

In Shanghai, the British Consul-General, R.W. Urquhart, stated to the press: ‘Every possible means of rescuing them [the crew of the Amethyst], either by an operation or a cease-fire order, will be taken.’ But in reality the mighty Royal Navy was running out of options. Vice-Admiral Mallen was loath to expose any more of his vessels to shore bombardment on the river, so some other way would have to be found to obtain the Amethyst’s release. In the meantime, the Repose moved down to the Whangpoo River, anchoring off the Shanghai Bund a safe distance from Communist shore batteries. American Consul-General John Cabot urged the 2,500 US citizens who remained in Shanghai to leave. The US Navy had enough ships to evacuate all of them before the city fell to the Communists, and also space to take off many other foreigners.

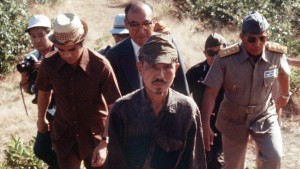

John Kerans was a thirty-three-year-old Second World War veteran and he wasted no time in organising the evacuation of the remaining wounded men and getting the Amethyst sea-worthy again. Soon afterwards, the PLA made contact, requesting a meeting between Kerans and the local PLA political officer, a Colonel Kung. Kung acted as a representative for Colonel Ye Fei, the local military commander. At their first meeting on 30 April, Kung demanded that Kerans sign a statement in which the British admitted to having ‘invaded’ Chinese territorial waters by steaming warships up the Yangtze, and having fired first on the PLA. Kerans refused, stating repeatedly that the Amethyst was going about her lawful business under the various treaties that had been signed between China and the Western Powers when she had been fired on by the PLA without warning or provocation. Naturally Kung refused to accept this. The Communists consistently refused to recognize any of the treaties that had been made under the Qing Dynasty or those by the subsequent Nationalist government, declaring them all to be ‘unequal’ and therefore unlawful. Only in 1989 did retired General Ye Fei finally admit that the PLA had fired first.

Kung and Kerans found themselves at an impasse. The Chinese informed Kerans that as long as the British behaved themselves the PLA batteries would not fire on the Amethyst, but if he tried to move the ship they would do so. Kerans and the Amethyst were now to be Chinese hostages, the PLA intention being to starve the crew into submission and force them to sign the face-saving admission of guilt. Kerans never wavered and instead settled down to a long siege.

The Amethyst remained at anchor and under PLA guns for ten weeks. The Chinese denied the vessel most supplies, but because a small steaming party only manned the ship since the 21st April battle and evacuation, the ship’s stores were sufficient to last. The Chinese played a cat-and-mouse game with Kerans. They made demands, sometimes offered concessions, such as permitting outgoing mail or supplying oil for cooking, but all the time trying to persuade or bully Kerans into signing a statement admitting that the Amethyst had opened fire first. The entire Chinese strategy was designed to lower the British sailors’ morale, but Kerans was wise to their tricks and he determined to make a run for Shanghai and the open sea when the opportunity presented itself.

One morale-booster for the British was the activities of Simon, the ship’s cat. He had miraculously survived his ordeal by shellfire and had resumed his extremely useful duties killing rats aboard the stationary ship. ‘There was a particularly large and ferocious rat on board that the crew nicknamed Mao Tse Tung. Mao and his followers were wreaking havoc on the ship’s dwindling supplies. The crew felt that Simon in his weakened state would be no match in a one-on-one with Mao.’ They underestimated Simon, and in duel to the death, Mao the rat was killed. Although Kerans did not have the same affinity for the animal as the crew, Simon had nonetheless helped to prevent a disease outbreak by killing off the vermin that infested the Amethyst, and his affection towards the crew was much appreciated leading to his promotion to the rank of “Able Seacat”.

During the early hours of 30 July 1949, the Amethyst slipped her chain and quietly moved downriver towards Shanghai, beginning a hazardous 104-mile dash for freedom. By now, the Communists had crossed the river and established gun batteries on both banks. If Kerans’s escape attempt was discovered his ship would have been blown out of the water by the PLA guns. Kerans’s preparations had included greasing the anchor cable to deaden the noise, and changing the ship’s silhouette with black-painted canvas screens erected forward to confuse the Chinese gunners as to her identity. The crew was all dressed in dark colours and all white parts of the ship’s superstructure had been painted out.

Just before Kerans gave the order to slip, a well-lit Chinese passenger ship, the Kiang Ling Liberation, came around a bend in the river heading for Shanghai. She was carrying refugees. Kerans decided to follow the Kiang Ling, using her as a pilot to navigate the treacherous shoals, and the Chinese vessel’s lights would also distract the PLA gunners, leaving the blacked-out Amethyst trailing in the shadows. However, this plan did not last long as the movement was spotted by the PLA and parachute flares shot into the night sky. Kerans immediately ordered ‘full ahead both’ and the Amethyst surged past the Kiang Ling as the Chinese batteries opened fire. Perhaps distracted by the lights on the Kiang Ling, the Chinese gunners failed to hit the Amethyst, though she returned fire with alacrity. The unfortunate Kiang Ling was pounded by Chinese shells, caught fire and eventually sank, and an unknown number of refugees were killed.

Two forts, Woosung and Par Shan, had protected the entrance to the Yangtze River for over a century. They were thirty-eight miles from the East China Sea and Shanghai. These forts, which had a long history of battles with the British, mounted modern 8-inch guns. If the forts opened fire on the Amethyst she would be destroyed.

In order to help the Amethyst reach the open sea, Admiral Brind ordered another C-class destroyer, HMS Concord, to enter the Yangtze and sit off the Woosung Forts with orders to bombard it if necessary. This was a very risky action, for the Concord was only armed with 4.5-inch guns. Now that the cruiser London had been sent for urgent repairs in Hong Kong following her battering up the Yangtze, the Concord would have to do. But the Concord’s skipper, Commander Ian Robertson, was prepared to do his duty, come what way.

Late on the evening of 20 July, Concord proceeded upriver. She was challenged by a Nationalist Chinese gunboat, but unmolested. The Concord anchored at 1.45am on 21 July, but shortly afterwards weighed anchor and proceeded up the Yangtze for twenty miles. At 2.20am the Concord spoke briefly with another Nationalist warship near the Tungshan bank buoy, anchored again, and after another brief period, set off once more. The telegraphist picked up a message from the Amethyst: ‘Woosung in sight.’ This was followed a little while later by ‘Concord in sight.’ The time was 5.25am, and the Concord spotted the battered Amethyst at a distance of three miles. Concord signalled the Amethyst: ‘Fancy meeting you again’, to which the Amethyst replied: ‘Never, repeat never, has a ship been more welcome.’

Commander Kerans signalled Admiral Brind, with a copy to the Admiralty in London: ‘Have rejoined the fleet, no damage or casualties. God save the King.’ Travelling in concert, at 7.15am the ships “secured from action stations”, which meant they were no longer ready to fight, and at 12.12pm the main engines rang off. They were kept at two hours notice for steam. Concord transferred stores and discharged 147 tons of fuel oil to the Amethyst – after so long under siege, the Amethyst’s tanks only contained seven tons of fuel. At 6pm Lieutenant T.J.D. Grant was drafted onto the Amethyst on temporary loan along with one signalman and one telegraphist.

At 10pm that night the Concord slipped from Amethyst and in company they set off for Hong Kong. A short while later they encountered the destroyer HMS Cossack. Concord was ordered to proceed on patrol leaving the Cossack to escort the Amethyst to Hong Kong. Due to the very sensitive nature of her mission, the Concord’s log book was taken out of service and replaced. The British were keen that there would be no trace of Concord’s ‘invasion’ of the Yantgze River, but this move has led to the part played by Concord’s crew being minimized or ignored, even though they placed themselves under the guns at Woosung, and were expecting a fight. This would also lead to the denial to the crew of the Naval General Service Service Medal with bar ‘Yangtse 1949’ that was given to the ship’s companies aboard the Amethyst, London, Black Swan, and Consort.

Of the forty-six British sailors who were killed during in the Yangtze Incident, twenty-three were buried with full military honours in Shanghai. Unfortunately, during the 1960s their graves were desecrated and eventually completely destroyed. Lieutenant-Commander Bernard Skinner was buried at sea off Shanghai as per the wishes of his widow in Hong Kong, while the remaining dead were buried in the Yangtze River.

It was perhaps only natural that an animal loving people like the British should seize upon the story of Simon, the ship’s cat, to help them come to terms with the Amethyst disaster. Simon was lauded in both the national and international press after the Amethyst returned to Plymouth in November 1949. At each and every port that the ship visited Able Seacat Simon was lauded and honoured alongside the Amethyst’s brave crewman. He was given the premier award for animal bravery, the Dickin Medal, as well as a medal from the Blue Cross. He was also given the Naval General Service Medal alongside his shipmates. One crewman from the Amethyst was given the full-time job of responding to the thousands of letters that people from all over the world wrote to the cat. On arrival in England, Simon was placed into routine quarantine at an animal centre in Surrey but he developed an infection caused by his war wounds and died on 28 November. His tiny coffin, draped in the Union Jack, was interred in a cemetery in Ilford, East London. Hundreds, including the entire crew of HMS Amethyst, attended his funeral.